Camera Anatomy - PhotoPlus : The Canon Magazine - anatomy camera

Dr. Neal E. Seymour (New Haven, CT): I appreciate your comment on the predictive validity of the study. We obviously designed our study with predictive validity in mind. We were determined to do our assessment of operative performance without using global ratings and maintaining a focus on errors because we felt that the study strategies would maximize the sensitivity in demonstrating skills transfer. In answer to your first question which pertains to the number of residents and level of training, I believe you were referring to the issue of construct validity. As I pointed out earlier, our study was not designed to test construct validity which has been demonstrated very clearly for the MIST-VR system in the past by a number of investigators including Anthony Gallagher, one of the investigators in the current study. We could see differences between residents at different PGY levels in the number of training sessions it took to achieve performance criterion levels. There were no statistically significant trends in that data, and I have not presented because of, as you rightly pointed out, the small size of the study.

You can not make a U-turn near the top of a hill, a curve or any other location where other drivers can not see your vehicle from 500 feet (150 m) away in either direction. U-turns are also illegal in business districts of New York City and where NO U-TURN signs are provided. You can never make a U-turn on a limited access expressway, even if paths connect your side of the expressway with the other side. In addition, it is prohibited for a vehicle to make a U-turn in a school zone.

Dr. Johnathan L. Meakins (Montreal, Quebec, Canada): I second the remarks of Dr. Pellegrini. It is noted that OR time is so precious and expensive that it can’t actually be used for practice; whereas, on the other hand, there is an old joke, the punchline of which is, “The way to Carnegie Hall is practice, man, practice.” So that is a part of what has been demonstrated.

No differences in baseline assessments were found between groups. Gallbladder dissection was 29% faster for VR-trained residents. Non-VR-trained residents were nine times more likely to transiently fail to make progress (P < .007, Mann-Whitney test) and five times more likely to injure the gallbladder or burn nontarget tissue (chi-square = 4.27, P < .04). Mean errors were six times less likely to occur in the VR-trained group (1.19 vs. 7.38 errors per case;P < .008, Mann-Whitney test).

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Be especially alert to individuals in wheel chairs, people pushing strollers, or someone pulling a wheeled suitcase behind them. They may be closer to the ground and hidden behind a car.

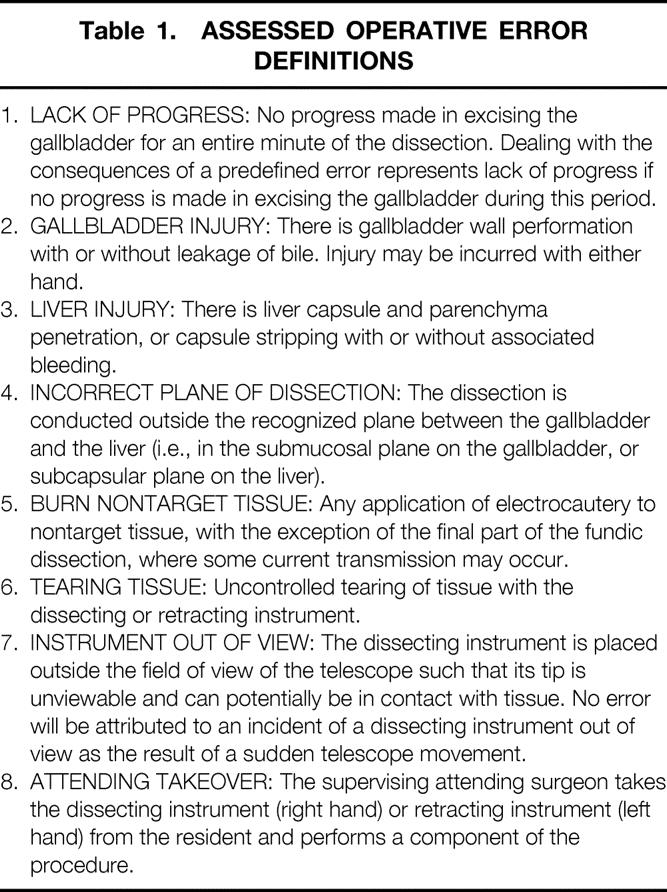

During unfettered review of archived videotapes of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, potential measures of surgical performance were collated and discussed by the four surgeon-investigators and one behavioral scientist involved in the study. From this list, eight events associated with the excisional phase of the procedure were defined as errors and chosen as the study measurements (Table 1). These measurements excluded any inferences that were not directly observable. All of the events were explicitly defined to facilitate interrater agreement. Clear guidance was given as to when an event was judged to have or have not occurred. The length of time of the gallbladder excision phase was also determined. Timing of length of procedure started with first contact of the electrosurgical instrument with tissue and ended when the last attachment of the gallbladder to liver was divided.

You should probably consider investing in a commercial grade body cam. Otherwise if you want a more discrete, then a small wearable spy camera should do the ...

The duration of the dissection for the VR-trained group was 29% less than in the ST group, although this difference did not achieve statistical significance (Fig. 3). Gallbladder injury and burn of nontarget tissue errors were five times more likely to occur in the ST group than in the VR group (one of each error in VR residents as compared to five of each error in the ST residents). Separate comparisons between the groups for these errors demonstrated statistical significance in both cases (chi square 4.27, df = 1, P < .039). ST residents were nine times more likely to be scored as lack of progress, with mean number of lack of progress errors per case of 0.25 versus 2.19 (VR vs. ST groups, respectively; Mann-Whitney, Z = −2.677, P < .008). There were no tearing tissue errors or noncontact cautery errors in either group. There was one liver injury, three dissection incorrect plane, and six attending surgeon takeover errors scored, all in the ST group. In all error categories except liver injury (one error in VR group) and tearing tissue (no errors either group), more errors were observed in the ST group than in the VR group (Fig. 4). The ST group made six times as many errors as the VR group (Fig. 5), with four times the variability in the performance of the VR residents as indicated by standard errors. The mean number of scored errors per procedure was significantly greater in the ST than in the VR group (1.19 vs. 7.38, Z = −2.76, P < .006, Mann-Whitney test).

Presented at the 122nd Annual Meeting of the American Surgical Association, April 24–27, 2002, The Homestead, Hot Springs, Virginia.

Unless prohibited, a three-point turn may be used to turn around on a narrow, two-way street. You may be required to make a three-point turn on your road test.

Approach the turn in the left lane. As you proceed through the intersection, enter the two-way road to the right of its center line, but as close as possible to the center line. Be alert for traffic that approaches from the road to the left. Motorcycles are hard to see, and it is hard to judge their speed and distance away. See the example below.

There were no significant differences in any of the initial battery of assessment tests noted between the VR and ST groups (Fig. 2). All residents randomized to the VR group successfully achieved the required criterion levels of performance in three to eight training sessions. All residents in both groups successfully completed the dissection of the gallbladder from the liver bed. The interrater reliability for the assessment of residents’ operative performance during video reviews was 91 ± 4% (range 84–100%).

Approach the turn from the right half of the roadway closest to the center. Make the turn before you reach the center of the intersection and turn into the left lane of the road you enter. See the example below.

Personal vehicles driven by volunteer fire fighters responding to alarms are allowed to display blue lights and those driven by volunteer ambulance or rescue squad members can display green lights. Amber lights on hazard vehicles such as snow plows and tow trucks, or the combination of amber lights and rear projected blue lights on hazard vehicles designed for towing or pushing disabled vehicles, warn other drivers of possible dangers. Flashing amber lights are also used on rural mail delivery vehicles and school buses to warn traffic of their presence. The vehicles that display blue, green or amber lights are not authorized emergency vehicles. Their drivers must obey all traffic laws. While you are not required to yield the right-of-way, you should yield as a courtesy if you can safely do so.

Go straightand turn left

Figure 4. Total error number for each error type. LOP, lack of progress; GBI, gallbladder injury; LI, liver injury; intraperitoneal, incorrect plane of dissection; BNT, burn nontarget tissue; TT, tearing tissue; IOV, instrument out of view; AT, attending takeover. In all error categories except LI and TT, a greater number of errors were observed in the ST group than in the VR group.

Figure 5. Total number of errors scored per procedure for VR and ST groups. The mean number of errors per procedure was significantly greater in the ST group than in the VR group (P < .006).

Students are certainly able participants in any VR basic skills acquisition program, and they stand to benefit in a number of ways. Seeing this technology may, in fact, influence a decision to pursue a career in surgery. However, our immediate focus has been on surgical trainees and on giving them the skills they need to perform laparoscopic surgery at a higher level when they enter the operating room.

Fig. 2. Results of fundamental abilities assessment. No significant differences were noted in visuospatial, perceptual, or psychomotor abilities between subjects randomized to ST and VR groups when assessed before the training phase of the study.

Was any individual in your study excluded because at the beginning they did not achieve whatever performance levels you have when you take this and other tests? And most importantly, did anyone fail to meet the preset criteria that you had established? Was anybody excluded from this study?

Flammable sensors capable of measuring across 14 different gases with just one factory calibration and no field calibration.

Cost issues (i.e., OR time, surgeon teaching time, etc.) need to be integrated with the cost of the simulators, how we create the software and how it gets disseminated and need to be integrated into use. These two cost issues need integration with the ways in which we as surgical educators reframe residency programs to deal with modern constraints. I just will mention the 80-hour workweek as an example. There is, however, a second constituency who may well need this kind of training. That is the surgeon in practice who has to deal with a new technique, a new technology, or a new operation, and needs to learn that in an appropriate way. What is the cost and the time required to create the kind of simulator model that you have got so that it might be applied to the second constituency; that is, those of who need to learn how to do something brand new?

Most traffic crashes occur at intersections when a driver makes a turn. Many occur in large parking lots that are open to public use, like at shopping centers. To prevent this type of crash, you must understand the right-of-way rules and how to make correct turns.

Drawing on the successful paradigm of flight simulation, Satava first proposed training surgical skills in virtual reality (VR) nearly a decade ago. 6 Since that time, with the advancement of desktop computing power, practical and commercially available VR-based surgical simulators and trainers have been developed. At Queen’s University, Belfast, and at Yale University such systems have been employed for training and assessment of surgical skills. 7–9 Results from both centers show that VR training results in technical skills acquisition at least as good as, if not better than, programs that employ conventional box trainers. 10,11

Go straight thenturn leftin spanish

Simulators can teach judgment. There are many other simulator paradigms where improved judgment is the major goal of doing simulations. This particular simulator, MIST-VR, is not designed to teach surgical judgment. Another surgical simulator, the sinuscopic simulator currently in use, does overlays of anatomic information and shows on a teacher-determined basis what anatomy is revealed to the participant on the simulator, and teaches decision-making based on a continuous, dynamic education process. Rather than doing a terminal phase instruction, this is real-time instruction were anatomic information can be presented to a person so that their judgment will be shown to be adequate or inadequate, as determined by the clinical situation. So, yes, judgment should be topped by simulators and in the future will be taught by simulators with the appropriate curriculum goals in mind.

The introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the subsequent rapid growth of minimal access surgery (MAS) have challenged conventional systems for surgical training and establishment of competency. After 1989, as MAS became more commonly practiced, it became clear that the laparoscopic approach was associated with a significantly higher rate of complications, 1 particularly during surgeons’ early experience with these procedures. 2 The underlying causes of these developments were complex but ultimately related to inadequate training of the skills necessary to overcome the psychomotor hurdles imposed by videoscopic interface. When higher complication rates with MAS were scientifically validated, 3 surgeons set about defining more structured training methods, such as the Wolfson Minimal Access Training Units in the United Kingdom. However, laparoscopic surgical training has for the most part remained relatively unstructured and patterned on the same mentor–trainee model that served surgical training objectives throughout the last century. At the onset of the 21st century, the surgical education establishment is searching for new and innovative training tools that match the sophistication of the new operative methods.

Dr. Neal E. Seymour (New Haven, CT): With regard to your first question, Dr. Pellegrini, none of the subjects were excluded based on the performance criteria levels that we established before they trained. We initially had some concerns that by having experienced laparoscopic surgeons use the MIST-VR to establish a performance benchmark, a new class of difficulty for the task would be created. We did not wish to set a target performance criterion level that could not be achieved by surgical residents at all PGY levels of training. During an early phase of the development of our methods, we tested the ability of residents who were not randomized for the actual study to reach those criteria and levels and found that they could, although there was significant variability in the amount of training that was required to accomplish this. Generally, more senior residents required less training, although the small “n” value does not permit more specific comment on construct validity. There were some differences noted among individuals in the study which I have not presented here today. These pertain to gender-specific performance with regard to the rate and consistency in skills acquisition. Ultimately, the achievement of performance criteria was not a problem for any of the subjects in this study and no one was excluded on that basis.

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Statistical comparisons were performed by chi-square analysis, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Mann-Whitney test (SPSS, Chicago, IL), with statistical significance taken at the P < .05 level.

Dr Ajit K. Sachdeva (Chicago, IL): I believe this a landmark study, as Dr. Pellegrini has mentioned. The study has demonstrated, through a very elegant study design, the transfer of psychomotor skills acquired in a virtual setting to the real environment. Thus, the predictive validity of the educational intervention has been demonstrated. Also, the measurement approach used by the authors is quite innovative. In the past, evaluations conducted by other investigators have involved the use of global ratings and, prior to that, checklists. The objective evaluation of errors rather than the evaluation of the psychomotor skills using global ratings or checklists is a move in the right direction. I have a number of questions for you, Dr. Seymour. First, although the cohort of residents was small, did you see any trends by level of learner? Was there a difference in the transfer of skills at the different levels of residents, from years 1 through 4? Second, what was the time interval between the completion of training in the virtual environment and evaluation of skills in the operating room? My third question relates to the second. If the time interval was long, was there any operative experience that might have contributed to the acquisition of the psychomotor skills, and thus have contaminated the results? Finally, what are your plans for further dissemination and validation of your approach? We certainly need larger data sets to further validate your findings, study other types of validity, and assess the generalizability of your approch.

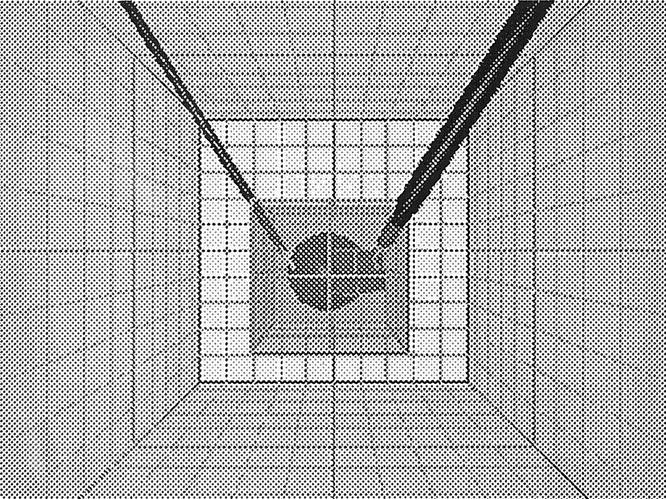

Four attending surgeons, all with extensive prior experience with laparoscopic procedures, completed 10 trials on the MIST VR “Manipulate and Diathermy” task (see Fig. 1) at the “Difficult” level to establish the performance criterion levels (mean error score = 50, mean economy of diathermy score = 2). The training goal for residents in the VR group was to perform the same task equally well with both hands on two consecutive trials at the criterion levels set by the experienced surgeons. Training sessions lasted approximately 1 hour. Training was always supervised by one of the authors (A.G.G. or N.E.S.), and explicit attention was paid to error reduction and economy of diathermy.

Keep your wheels straight until you actually begin to make your turn. If your wheels are turned and you are hit from behind, your vehicle could be pushed into the oncoming lane of traffic.

Left turn andrightturnat the same time

Could you tell us about the individual differences among the residents at the starting time? We found significant differences at the beginning of the training phase, and very little difference, with everybody achieving a performance within 10% of each other, at the end of the training phase.

Always signal before you turn or change lanes. It is important that other highway users know your intentions. The law requires you to signal a turn or lane change with your turn lights or hand signals at least 100 feet (30 m) ahead. A good safety tip is, when possible, to signal your intention to turn before you begin to brake or make the turn. The proper hand signals are shown below.

The use of VR surgical simulation to reach specific target criteria significantly improved the OR performance of residents during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This validation of transfer of training skills from VR to OR sets the stage for more sophisticated uses of VR in assessment, training, error reduction, and certification of surgeons.

Dr. Leslie H. Blumgart (New York, NY): Three brief questions. Firstly, these operations in your study were performed under the supervision of an attending surgeon. Was it the same attending surgeon throughout? Or could the results have been influenced by different comments from the attending surgeon in the two groups? Secondly, can you use these techniques to teach judgment? For instance, in cholecystectomy, can you, using these virtual reality approaches, teach the surgeon when to convert to an open operation? Finally, can virtual reality be used to train surgeons to do operations which are not necessarily approachable by minimally invasive methods?

2022810 — The oxidizing agent is a substance that causes oxidation by accepting electrons; therefore, its oxidation state decreases. The reducing agent is ...

Dr. Neal E. Seymour (New Haven, CT): With regard to the surgeon in practice, I think that we are waiting on the sort of simulations that train very, very specific procedures rather than focus on acquisition of basic skills, although certainly there is still probably plenty of room for basic skills improvement in that target group of surgeons who might want to increase laparoscopic skills. Getting this technology out to surgeons in practice presents an entirely different set of problems that we are currently dealing with. As the machines become more advanced and more available, there will be increased opportunities for community surgeons to have access to simulators to hone skills. We have not worked out the details of how best to achieve that, but it is certainly something to give consideration to.

One of the things that we have done is to bring to our laboratories medical students. In fact, we studied fourth-year medical students. I believe that if we want to reverse the trend away from surgery, as President Debas so eloquently described yesterday, we should expose our students to these environments early on in their careers. And herein, I think, lies the strength of the study. Indeed, it is surgeons that have developed and are at the forefront of virtual reality simulation. And since once created, this environment can be modified for other tasks, I believe that surgeons are in a unique position to offer to train medical students in basic skills. Early exposure to these individuals, establishing relationships and friendship at an early stage of medical student careers, I think will have, or may have, a profound effect on their ultimate career choice. Perhaps the authors may wish to comment on this, a less obvious but I think a much more important aspect of their work.

The use of VR surgical simulation to train skills and reduce error risk in the OR has never been demonstrated in a prospective, randomized, blinded study.

Dr. Carlos A. Pellegrini (Seattle, WA): The authors of this very important paper tested, in a randomized, double-blind study, the hypothesis that virtual reality surgical simulation training would improve operating room performance. The objective assessment of the laparoscopic cholecystectomy showed that the VR training definitely improved performance when compared to a group of residents trained by traditional means.

No matter how sophisticated laboratory assessment and training methods become, their relationship to OR performance must be established. Our operative assessment methodology was designed to measure observable surgical performance. No inferences were drawn about why the resident performed in a particular way. Global ratings of resident performance and Likert-type scales were avoided in favor of the fixed-interval time span sampling method that identified the presence or absence of predefined error events. This emphasis on observable events resulted in interrater reliability levels that remained above 0.8 throughout the study, with effective blinding of observers to study participant training status. Prior efforts to quantify performance during laparoscopic cholecystectomy have examined similar errors, but with a more global view of the procedure. 16 Although clearly feasible and reliable, this methodology was somewhat time-consuming during both the training and scoring phases.

The Leadership Development Program (LDP) is for you. Participants learn valuable leadership skills, gain exposure to the roles and mission of ASCO.

All residents performed laparoscopic cholecystectomy with one of surgeon-investigators, who were blinded to the subject’s training status. Before procedures, all were asked to view a short training video demonstrating optimal performance of excision of the gallbladder from the liver using a hook-type monopolar electrosurgical instrument. This video defined specific deviations from optimal performance that would be considered errors. After the viewing, all residents were given an eight-question multiple-choice examination that tested recognition of these errors. During surgery, after division of the carefully identified cystic structures, residents were asked to perform the gallbladder excision using a standardized two-handed method. This phase of the procedure was video-recorded with voice audio by the attending surgeon describing any interventions (attending takeover of one or both instruments). Procedures with attending takeover were flagged for examination of audio.

Approach the turn from the right half of the roadway closest to the center. Try to use the left side of the intersection to help make sure that you do not interfere with traffic headed toward you that wants to turn left. Keep to the right of the center line of the road you enter, but as close as possible to the center line. Be alert for traffic, heading toward you from the left and from the lane you are about to go across. Motorcycles headed toward you are hard to see and it is difficult to judge their speed and distance away. Drivers often fail to see a motorcycle headed toward them and hit it while they turn across a traffic lane. See the example below.

I absolutely agree with you on the value of VR as a component of a fundamental skills acquisition program, even at the present level of technology of widely available virtual reality simulators and trainers. These devices can, in conjunction with an appropriate curriculum, provide a means of both training and assessing performance. It is not to my mind a replacement for mechanical box trainers and other training techniques, particularly if one examines more complex tasks which currently cannot be achieved in virtual reality. Suturing and knot-tying are VR tasks in development that most readily come to mind in this regard. Simulation of these tasks is a major goal for the engineers and software developers who are currently working in this area. Until this goal is achieved, VR will be extremely valuable for basic skills but somewhat limited for advanced skills acquisition.

An emergency vehicle that uses lights and a siren or air-horn can be unpredictable. The driver can legally exceed the speed limit, pass red lights and STOP or YIELD signs, go the wrong way on one-way streets and turn in directions not normally allowed. Although emergency vehicle drivers are required to be careful, be very cautious when an emergency vehicle heads toward you.

Do not try a U-turn on a highway unless absolutely necessary. If you must turn around, use a parking lot, driveway or other area, and, if possible, enter the roadway as you move forward, not backing up.

Move into the left lane when you prepare to turn. If the road you enter has two lanes, you must turn into its left lane. See the example below.

The results of this study demonstrate that it is feasible to train operative skills in virtual reality in surgical trainees without extensive prior MAS experience. Residents who trained on MIST VR made fewer errors, were less likely to injure the gallbladder and burn nontarget tissue, and were more likely to make steady progress throughout the procedure. During VR training it was made clear to residents that speed was not a major training parameter. Instead, training emphasized safe and economical use of electrosurgery instruments and positioning of “tissue” with the nondissecting hand. Completion of the training phase was carefully defined based on objective performance criteria established in advance by experienced laparoscopic surgeons. In the planning phase of the study, it was uncertain whether these criterion levels were set too high, but pilot testing demonstrated that these levels could be attained by residents. This is an important point since if the criterion level were set too high, study participants would not be able to reach it. These targeted performance levels may have contributed to the consistent performance demonstrated by the VR-trained group in the OR phase of the study. The requirement that explicit performance criterion levels be reached on two consecutive trials made it unlikely that the resident could achieve it by chance. The performance criterion level established by laparoscopic surgeons at Yale University will need to be validated by the larger surgical community to determine whether they are appropriate measurements and levels to reflect “expert” performance.

You must yield the right-of-way to fire, ambulance, police and other authorized emergency vehicles when they respond to emergencies. They will display lights that are flashing red, red and blue or red and white and sound a siren or air-horn. (Vehicles responding to emergencies for a Police Department, Sheriff Department or the New York State Troopers are not always required to use an audible siren or horn.) When you hear or see an emergency vehicle heading toward your vehicle from any direction, safely pull over immediately to the right edge of the road and stop. Wait until the emergency vehicle passes before you drive on. If you are in an intersection, drive out of it before you pull over.

58K views · Sometimes, you find the perfect connection. #gaming. 307K ... #farmingsimulator22 #gaming. 62K views · Farm Production Pack: Available April ...

Note: Practice quizzes are available only for those sections of the manual covering rules of the road (Chapters 4 through 11 and Road Signs).

Report no less than once every three months, by way of a report to the Board or a publicly available website, on the number of requests made by members of the ...

Concurrent with the growth of MAS, separate developments have brought considerable focus on the issue of errors in medicine. The “Bristol Case”4 in the U.K. and the “To Err is Human”5 report published by the Institute of Medicine in the United States suggested that better training and objective assessment would be key strategies in attaining the goal of reduced medical errors. Surgeons were already sensitive to these issues and have accepted the idea that new and better evidence-based training is necessary and achievable.

I am probably not the best person to address the issue of cost of VR training, although I am aware of the considerable cost of the machines that we are using. It is not clear who is best able to pay the development costs of more advanced medical simulation technology or how to generate interest in this sort of endeavor among venture capitalists. I think the fundamental question boils down to who pays for surgical education. In the case of flight simulators, military simulators, and business simulators, it is quite obvious where the benefits lie and intense investment has produced machines that are light years ahead of what I have shown you, and what we currently use today. Again, I think that sorting out how to get money into surgical education is the fundamental problem. Simulators will certainly be a component of the educational process, but producing the best possible simulators is going to take dollars.

You must pull over and stop for an emergency vehicle even if it is headed toward you in the opposite lane of a two-way roadway.

The Blackhawk TASER® 7 Holster features a distinctive draw motion that helps prevent confusing weapons under stress.

Figure 1. MIST VR screen appearance on “Manipulate and Diathermy” task. The sphere, which must be precisely positioned within a virtual cube, presents a target for the L-hook electrosurgery instrument. Objects may be positioned anywhere within the defined operating space.

For the purposes of this investigation, we have chosen a simple operative task that emphasizes technical skills. “Errors” in operative technique were defined as specific events that represented significant deviations from optimal performance, without linking these events to adverse outcomes or proximate causes. The identification and measurement of these errors permitted assessment of the effectiveness of VR training specifically intended to reduce their incidence. The simplicity of the operative procedure aided in the attainment of this study goal. However, competency comprises disparate cognitive and manual skills elements that do not necessarily lend themselves to unified testing. Anticipating that VR training will rapidly become more varied and realistic, more sophisticated methods of isolating and measuring specific skills in the OR are still needed. We envision the extension of these training tools to other procedures with the aim of eliminating behaviors that lead to adverse clinical outcomes.

The following illustrations show the correct position of your vehicle for turns. These positions are from requirements in the law, and are not just good advice.

Traffic signs, signals and pavement markings do not always resolve traffic conflicts. A green light, for example, does not resolve the conflict of when a car turns left at an intersection while an approaching car goes straight through the intersection. The right-of-way rules help resolve these conflicts. They tell you who goes first and who must wait in different conditions.

As you prepare to turn, get as far to the right as possible. Do not make wide, sweeping turns. Unless signs direct you to do otherwise, turn into the right lane of the road you enter. See the example below.

202068 — Despite the fact that tasers deliver a 50,000-volt jolt, it is thought that there is little risk of cardiac or heart problems, according to Dr.

The validation of VR training in training operative skills marks a turning point in surgical education. The potential exists to train a resident to a high level of objectively measured skill before he or she is permitted to operate on a patient. VR trainers and simulators offer the advantage of allowing as much training as is required to achieve the training goal. During our study, an investigator observed and instructed the residents during training exercises in order to validate the system. In the immediate future surgical trainees will be able to train whenever they choose, with their performance continuously assessed by the simulator until proficiency in the selected task is attained. With proper software, computer mentoring of the training task is also feasible. The implication is that the surgical education process will soon have the ability to “train out” the learning curve for technical skills on a simulator, rather than on patients; and that a high level of mentoring can be provided without consuming an inordinate amount of a supervising surgeon’s time. VR simulators maintain a log of performance over time, providing an automatic quality assurance tool for objectively assessing the advancement of an individual’s basic technical skills for the program director. It must be emphasized that many more skills are incorporated into the technical training of a surgeon (including the cognitive skills of anatomical recognition, decision making, alternate planning, and so forth), and that the simulators are but one part that can contribute to the overall improvement of performance and assessment of proficiency. Nevertheless, our study validates for the first time the role of VR training on the ability of surgical residents to perform an operative procedure with an improved and, arguably, safer performance. Our findings therefore support the introduction of VR training into surgical education programs.

Turnto theleft Turnto the right song

If you hear a siren or air-horn close by but do not know exactly where the emergency vehicle is, you must safely pull over to the right-side edge of the road and stop until you are sure it is not headed toward you.

Sixteen surgical residents (PGY 1–4) had baseline psychomotor abilities assessed, then were randomized to either VR training (MIST VR simulator diathermy task) until expert criterion levels established by experienced laparoscopists were achieved (n = 8), or control non-VR-trained (n = 8). All subjects performed laparoscopic cholecystectomy with an attending surgeon blinded to training status. Videotapes of gallbladder dissection were reviewed independently by two investigators blinded to subject identity and training, and scored for eight predefined errors for each procedure minute (interrater reliability of error assessment r > 0.80).

However, having said that, direct prospective comparison of box trainers tasks and the MIST-VR in basic skills acquisition anticipatory to the development of laparoscopic suturing and knot-tying abilities have shown that the VR simulator prepares trainees equally well if not better than a box trainer. The training used with the box trainer in that study consisted of the Rosser drills, a well-validated method of preparing trainees and students to do laparoscopic suturing and knot-tying. Preliminary studies like this prompted us to focus on VR as a means of acquiring basic skills in preparation for the OR.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Each procedural video was viewed without audio by two surgeon-investigators blinded to operating team members. The gallbladder excision phase of the procedure was scored on a minute-by-minute basis using a scoring matrix (see Fig. 1) that enabled the observers to record whether an error had or had not occurred during each 60-second period. Errors were recorded using fixed-interval time span sampling (one-zero sampling) described by Martin and Bateson, 14 where a single error event is scored irrespective of how many times during the 1-minute defined period it occurred. Attending takeover events were scored afterward based on review of the flagged videos. Interobserver agreement was determined as described by Kazdin for interval assessments according to the equation: agreements/(agreements + disagreements) times 100. 15

The MIST VR system (Frameset v. 1.2) was run on a desktop PC (400-MHz Pentium II, 64-Mb RAM) with tasks viewed on a 17-inch CRT monitor positioned at operator eye level. The video subsystem employed (Matrox Mystique, 8-MB SDRAM) delivered a frame rate of approximately 15 frames per second, permitting near-real-time translation of instrument movements to the video screen. The laparoscopic interface input device (Immersion Corporation, San Jose, CA) consisted of two laparoscopic instruments at a comfortable surgical height relative to the operator, mounted in a frame by position-sensing gimbals that provided six degrees of freedom, as well as a foot pedal to activate simulated electrosurgery instruments. With this system, a 3-D “box” on the computer screen represents an accurately scaled operating space. Targets appear within the operating space according to the specific skill task selected and can be grasped and manipulated with virtual instruments (Fig. 1). Each of the different tasks is recorded exactly as performed and can be accurately and reliably assessed.

Go straight thenturn leftin French

Dr. Neal E. Seymour (New Haven, CT): The four attending surgeons who participated in this study did so because of their interest in laparoscopic surgical training. We had a very, very clear protocol which addressed issues of surgeon behavior in the OR, emphasizing what behaviors would and would not be appropriate for the study. Certainly, patient safety was the major concern. In the case of a resident who was not performing the necessary task appropriately, and who was not responding to verbal instructions, would have one or both instruments taken away by the attending. We regarded such an event as an error and as one of the study metrics. The threshold of individuals to intervene is inevitably going to very variable however, we went to great lengths to try to preserve some uniformity of behavior based on preliminary meetings, discussion, establishment of appropriate OR behaviors, and I think to a very great extent we achieved that. But your question is a difficult one to answer and a difficult problem to test.

Correspondence: Neal E. Seymour, MD, Department of Surgery, Yale University School of Medicine, TMP 202, 330 Cedar Street, New Haven, CT 06520-8062.

Drivers must exercise due care to avoid colliding with any vehicle that is parked, stopped or standing on the shoulder or any portion of a highway.

However important these details may be, I would like to make sure that we do not miss the forest for the trees. The real contribution of this presentation, as I see it, is the demonstration that today, using computer simulation and virtual reality environments, we can teach residents skills that in the past we could only do in the operating room or at best in the animal laboratories. Virtual reality simulators allow students of surgery to practice as many times as they need to, which we found to be a very important element of learning. I think that this would definitely improve the nature of the learning experience, and, most definitely, the quality of life of the resident.

Turn leftsign

Turn leftmeaning

Approach the turn from the right half of the roadway closest to the center. Enter the left lane, to the right of the center line. When traffic permits, you can move out of the left lane. See the example below.

You can make a U-turn only from the left portion of the lane nearest to the centerline of the roadway, never from the right lane. Unless signs tell you otherwise, you can make a U-turn when you get permission to proceed by a green arrow left-turn traffic signal, provided it is allowed and you yield to other traffic.

Turnto theLeft Turnto the Right

Our 1050x750mm road safety signs are made of high-quality, durable aluminium, which is weather-resistant and can withstand harsh outdoor conditions.

Fire Extinguisher Signs · 3-Way - Glow-in-the-Dark, "Fire Extinguisher". S-19262 · 3-Way - Glow-in-the-Dark, "Fire Extinguisher". DESCRIPTION, Glow-In-The-Dark.

The time interval between completion of the training and performance of the operative procedure was kept to a minimum with some variability due to the vagaries of operative scheduling. Residents were able to do a laparoscopic cholecystectomy with one of the surgeon-investigators within two weeks of the completion of training. Although I think that pushing the operative procedure out to two weeks introduced some question that there might be time-dependent attenuation of the effect of the training, that proved not to be the case. As to our future work in this area, we have shifted our focus to higher end, high fidelity simulators and are examining more sophisticated operative tasks such as clip application and tissue division in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. It is fair to say that these more advanced simulators are much more interesting and exciting for participants to use. This relates to the perception of a more sophisticated task, and the face validity of manipulating recognizable tissue and anatomic structures. The problems of devising the appropriate metrics for the simulators are being solved at present time. As this work evolves, I believe we are going to obtain some very interesting data with these high fidelity simulators as well.

Sixteen surgical residents (11 male, 5 female) in postgraduate year (PGY) 1 to 4 in the Yale University School of Medicine Department of Surgery participated in this study. All study participants were randomly assigned to either a study group that would receive VR training in addition to the standard programmatic training (ST) appropriate for PGY level, or a control group that would receive ST only. Participants were stratified by PGY. All residents in both groups completed a series of previously validated tests to assess fundamental abilities. Visuospatial assessment included the pencil and paper Card Rotation, Cube Comparison, and Map Plan tests. 12 Perceptual ability (reconstruction of 3-D from 2-D images) was assessed on a laptop computer with the Pictorial Surface Orientation test (PicSOr). 13 Psychomotor ability was assessed with the Minimally Invasive Surgical Trainer-Virtual Reality (MIST VR) system (Mentice AB, Gothenburg, Sweden) with all tasks set at medium level of difficulty.

The most important goal of any training method is to increase the level of skill that can be brought to bear on a clinical situation, but to date no studies have established a clear benefit of VR training that transfers to surgeon skill measured in the operating room (OR). Our current study, a component of the program project “VR to OR,” was undertaken to determine whether training on VR in the skills laboratory generalizes to the clinical OR. A commonly performed laparoscopic procedure was selected for examination, along with a VR trainer task that was felt to most effectively train the desired operative skill.

A study by our own group in which residents were trained using artificial tissue-like materials shows that these exercises significantly enhanced performance and decreased errors when doing a cholecystectomy in a pig by the residents that were trained this way. Our system allowed us to determine performance objectively at every step of the training phase.

When driving on parkways, interstates and other controlled access roads with multiple lanes, due care includes moving from the lane immediately adjacent to where such vehicle is parked, stopped or standing unless traffic or other hazards prevent doing so safely. When encountering parked, stopped or standing authorized emergency vehicles and hazard vehicles with emergency lights or hazard lights activated, motorists must also reduce their speed.

Ms.Cici

Ms.Cici

8618319014500

8618319014500