Beam expander - galilean beam expander

As needs to be emphasized, this applies only to the imaging of extended objects and not to the imaging of point sources.

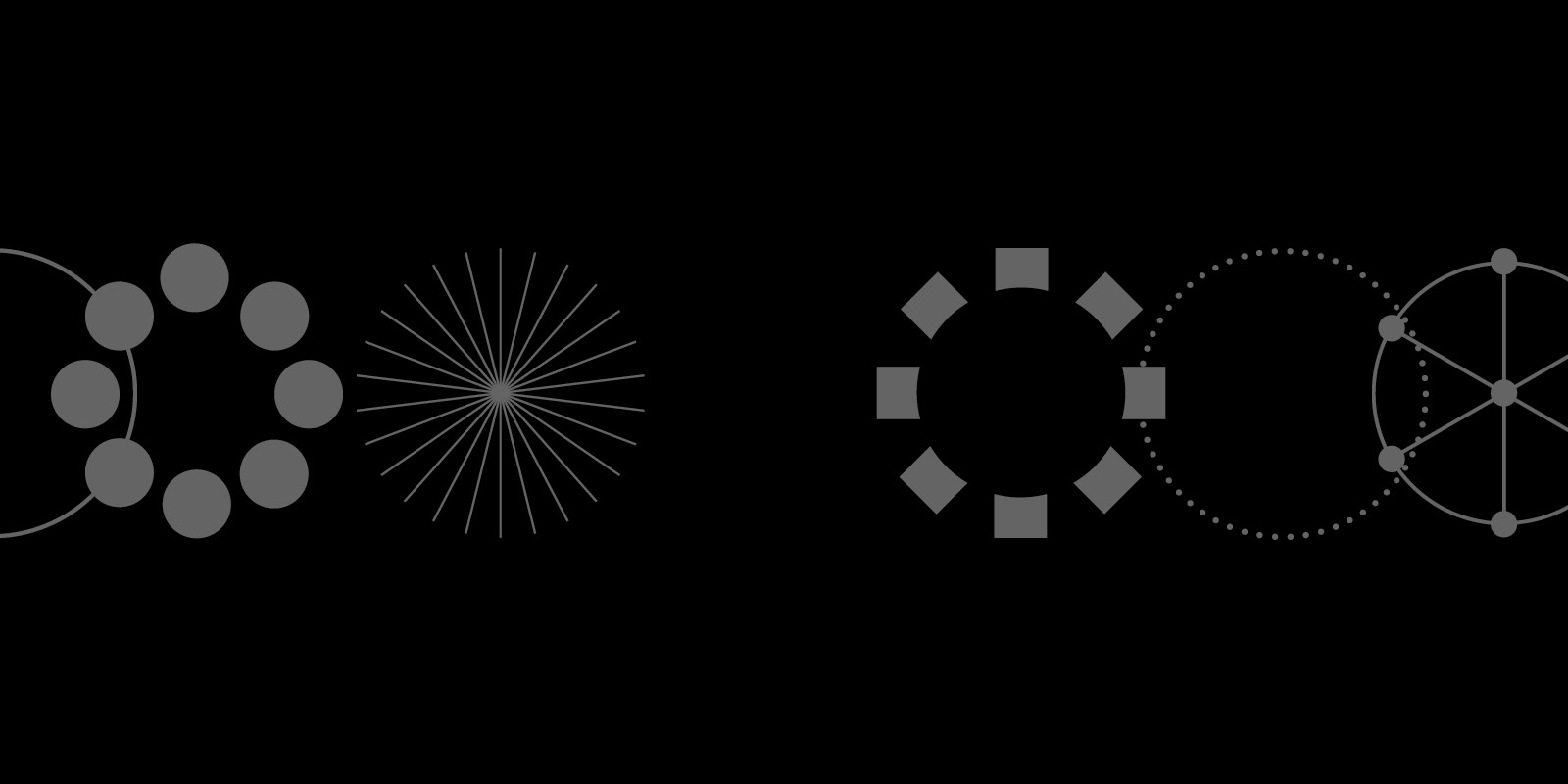

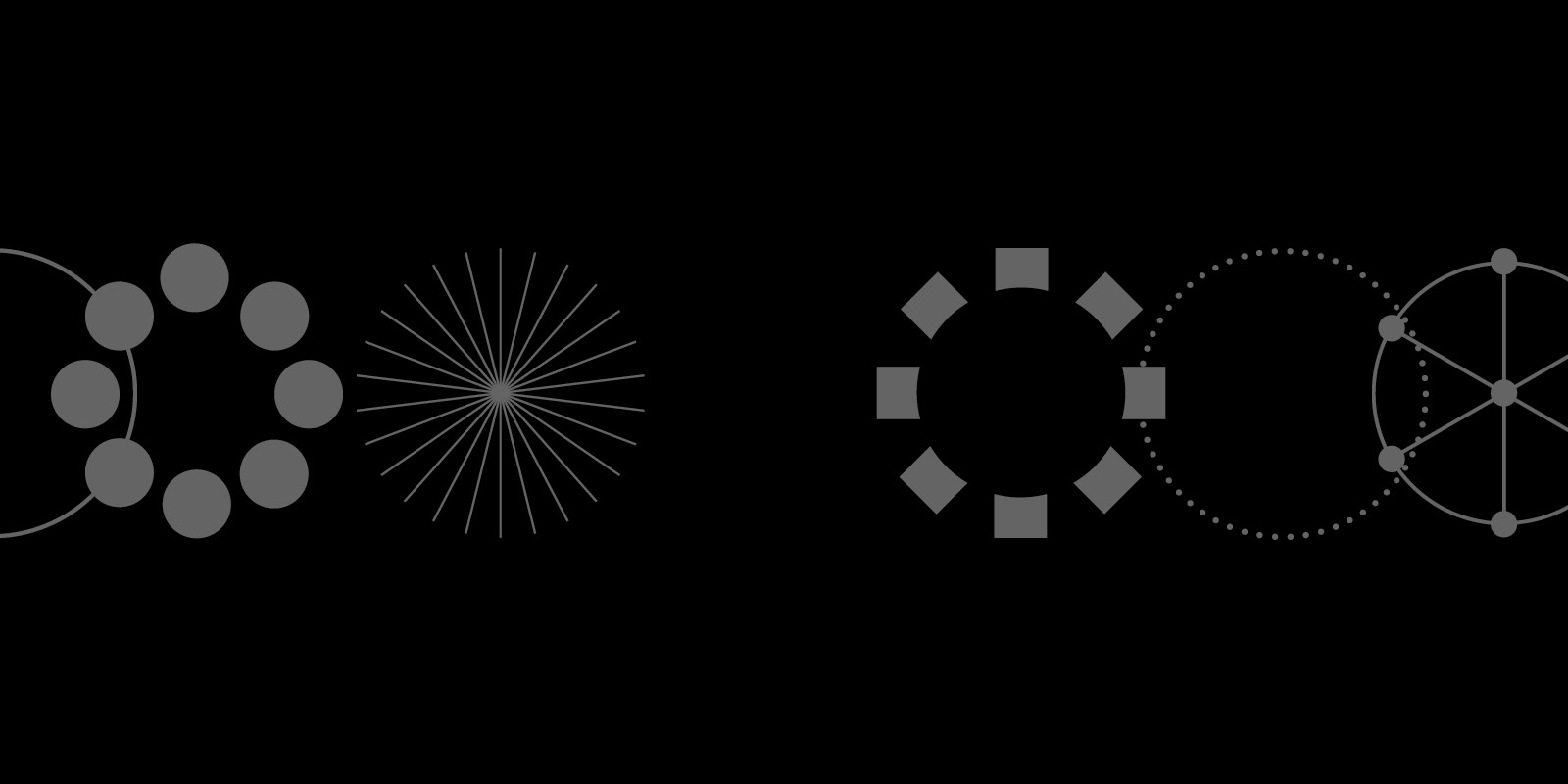

Left panel: an extended image obtained through a classical telescope. The width of the diffraction pattern equals λ/D = 30 pixels. Middle panel: each photon produces a set of 35 clones. In the absence of a coincidence detection the angular resolution is not improved. Right panel: the average position of the 36 photon clones is kept as the signal – the angular resolution is improved by a factor 6. In this numerical simulation the contribution from spontaneous emissions is neglected. The initial high-resolution image was provided by J. Schmoll.

Region * United States Canada Afghanistan Aland Islands Albania Algeria American Samoa Andorra Angola Anguilla Antarctica Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Aruba Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Brazil British Indian Ocean Territory British Virgin Islands Brunei Darussalam Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Cape Verde Cayman Islands Central African Republic Chad Chile China Christmas Island Cocos (Keeling) Islands Colombia Comoros Congo (Brazzaville) Congo, (Kinshasa) Cook Islands Costa Rica Croatia Cuba Curaçao Cyprus Czech Republic Côte d'Ivoire Democratic Republic of the Congo Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic East Timor Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Faroe Islands Fiji Finland France French Guiana French Polynesia French Southern Territories Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Gibraltar Greece Greenland Grenada Guadeloupe Guam Guatemala Guernsey Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Honduras Hong Kong, SAR China Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iran, Islamic Republic of Iraq Ireland Isle of Man Israel Italy Ivory Coast Jamaica Japan Jersey Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati Kosovo Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Lao PDR Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Libya Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Macao, SAR China Macedonia Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Martinique Mauritania Mauritius Mayotte Mexico Micronesia, Federated States of Moldova Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Montserrat Morocco Mozambique Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands Netherlands Antilles New Caledonia New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Niue Norfolk Island North Korea North Macedonia Northern Mariana Islands Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Palestine Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Pitcairn Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Romania Russian Rwanda Réunion Saint-Barthélemy Saint Helena Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint-Martin Saint Pierre and Miquelon Saint Vincent and Grenadines Samoa San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands Somalia South Africa South Korea South Sudan Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Svalbard and Jan Mayen Islands Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Syria Taiwan Tajikistan Tanzania, United Republic of Thailand Togo Tokelau Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Turks and Caicos Islands Tuvalu U.S. Virgin Islands Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Vatican City Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic) Vietnam Wallis and Futuna Islands Western Sahara Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe

We have provided a first, conceptual view of the elements that should be brought together in order to beat the diffraction limit of a telescope. The technological feasibility of the proposed scheme is still uncertain, and as the technology keeps moving forward, we expect that the set-up will be expanded and modified. Our main aim is to bring attention to the considerable long-term potential of non-linear optics for astronomical imaging.

Future progress of astronomy will depend on methods to extract the maximum possible information out of every photon. In the following we consider the use of photon-cloning devices to achieve extremely high angular resolution behind moderately sized telescopes. Caves (1982) has shown that it is impossible to use optical amplification to overcome the diffraction limit. The minimum amount of noise is such that the gain due to stimulated emission is just offset. On the other hand, this limitation has been reformulated in recent years: it is possible to reduce the noise contribution on a fraction of incoming photons (Ralph & Lund 2009; Barbieri et al. 2011). Not every incoming photon is then amplified, but when it is amplified the added noise is well below the minimum required by the Heisenberg principle. Such a non-deterministic amplification relies on the use of a trigger signal. Non-deterministic noiseless amplification implies the possibility to beat the diffraction limit behind a telescope at the price of a loss in sensitivity. This is now discussed.

The main aim of this article is to motivate further discussions on the use of non-linear optical processes for astronomy. Today’s telescopes still rely on classic processes, such as the diffraction and interference of light. But this will change and intensity interferometry, developed by Hanburry-Brown and Twiss, can already be mentioned as an exception (Brown & Twiss 1957, 1958a,b,c; Foellmi 2009; Dravins et al. 2012). Since intensity interferometry was first proposed in the 1960s, quantum optics has made substantial progress and the future of astronomy may well lie in the use of novel quantum optical mechanisms. As the challenges associated with building ever larger telescopes increase, processes such as stimulated emission, quantum entanglement and quantum non-demolition measurements will offer possibilities well worth to be explored. Eventually they may allow to overcome the classic diffraction limit and thus to obtain high-angular resolution even with small single-dish telescopes.

We propose to implement the trigger signal via a QND measurement. When photons arrive on a detector – e.g. the retina or a CCD chip – they interact with atoms, the energy of the photon is transmitted to the atom and the photon is thereby destroyed. The same applies to the usual discrete photon-counting procedures. In a QND measurement, the photon is detected, but not destroyed (Braginsky et al. 1992; Nogues et al. 1999). This uses quantum entanglement: the photon interacts with a quantum probe, typically an atom in an excited state (Guerlin et al. 2007; Birnbaum et al. 2005; Wilk et al. 2007). The presence of the photon changes the polarization state of the atom, but it does not de-excite the atom. The photon therefore keeps its momentum. The polarization state of the atom is measured via Raman interferometry and the outcome of the measurement determines the presence or absence of a photon. Since the probe and the photon are entangled, the state of the photon is likewise constrained, but, crucially, the photon is not destroyed. If the constraint is weaker than the constraint introduced by the passage through the telescope aperture, the photon’s momentum is not modified. This then serves as an ideal trigger measurement. The photon continues its way through the telescope: it passes the medium of excited atoms, stimulates the emission of clones and the set of identical photons arrives on the detector. The detector read-out is conditioned on the trigger signal. Note that the signal registered by the QND measurement need not arrive at the detector faster than the photon: the detector is read out continuously and the signals of interest are sorted out by subsequent processing.

Left panel: an extended image obtained through a classical telescope. The width of the diffraction pattern equals λ/D = 30 pixels. Middle panel: each photon produces a set of 35 clones. In the absence of a coincidence detection the angular resolution is not improved. Right panel: the average position of the 36 photon clones is kept as the signal – the angular resolution is improved by a factor 6. In this numerical simulation the contribution from spontaneous emissions is neglected. The initial high-resolution image was provided by J. Schmoll.

A distorted on-axis wavefront: the photon passes the pupil at point A at time t, while it crosses the pupil at point B at a later time t + dt. This induces different arrival times on the detector. The two events (the passage of the pupil at points A and B) are thus distinguishable, and the position of the photon in the pupil plane can be inferred with a precision better than D. This improved precision implies a larger uncertainty on the momentum: the images are blurred.

Conclusions. The main conclusion is the possibility in principle to improve the angular resolution of a telescope beyond the diffraction limit and thus to achieve high-angular resolutions with moderately sized telescopes.

Abbediffraction limitderivation

Let τ = 1/A be the radiative decay time of the excited atoms, where A is the Einstein coefficient of spontaneous emission. Let dt be the time spent by the photon in the cavity, dt=r Hc(2)where r denotes the number of passages in the cavity. The cavity has a cross section S = πD2/4 and a thickness H. c is the speed of light. Let N − 1 be the average number of clones created per incoming photon: N−1=σS Ir(3)I is the number of excited atoms in the cavity. σ is the cross-section of the excited atoms: σ=λ48πc Δλ A(4)where λ and Δλ are the spectral wavelength and bandwidth. Let M be the number of spontaneous emissions within the diffraction angle, during the time spent by the photon in the cavity: M=θ24πIA dt(5)where θ = λ/D. The number of spontaneous emissions should be small compared to the number of stimulated emissions. This constrains the cavity thickness: M≪N−1H≪2π λ2Δλ·Let ρ be the number of excited atoms per unit volume: ρ = I/HS. An improvement in angular resolution by a factor f requires: f2=Nρ r=f2−1σ H≫π (f2−1)2 Δλλ2 1σ·Assume the amplifier parameters of a dye laser (Bass et al. 1995): λ = 0.58 μm, Δλ = 0.06 μm and σ = 1.2 × 10-20 m2. An improvement in angular resolution by a factor f = 10 requires:

Whatis the diffraction limitofatelescope

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Our knowledge of the Universe is largely derived from the photons that are collected by astronomical telescopes. Larger telescopes are being built to improve the sensitivity and angular resolution of astronomical observations. Increased sensitivity can also be achieved via longer exposure times. Improved angular resolution, however, does require larger telescopes or longer interferometric baselines. Current telescopes have diameters of 10–20 m, and 30–40 m diameter telescopes are being planned. Higher resolutions are obtained with interferometers, when wavefronts pass through several distant telescopes. In either case, telescope or interferometer, the diffraction limit is attained after a careful correction for the effects of atmospheric turbulence (Roddier 1981). This correction becomes ever more complicated as telescope sizes and interferometric baselines increase (Macintosh & Beuzit 2011; Ellerbroek 2011; Hubin 2011).

Consider a photon emitted by an astronomical object. Before reaching the telescope, the photon is spread out over a large surface centered around the object. When the wave passes the telescope aperture the uncertainty of the lateral position is reduced to the aperture radius, Δx = r. In line with the Heisenberg principle there is then an uncertainty, Δpx ≥ ħ/2r = ħ/D, of the lateral momentum, and in consequence, the initial direction cannot be retrieved with a precision better than the diffraction limit, λ/D, where λ is the spectral wavelength and D is the aperture diameter. Astronomical features that are separated by less than the diffraction limit cannot be distinguished. The solution consists in building larger telescopes. If the aperture of the telescope is increased, the knowledge of the photon-position in the aperture is reduced, Δx is enlarged and the uncertainty on the momentum diminishes. The diffraction patterns become more narrow, and smaller astronomical features can be distinguished.

Aims. We examine the possibility of overcoming the diffraction limit of a telescope through photon cloning processes, heralded by trigger events. Whilst perfect cloning is ruled out by quantum mechanics, imperfect cloning is attainable and can beat the diffraction limit on a reduced fraction of photons.

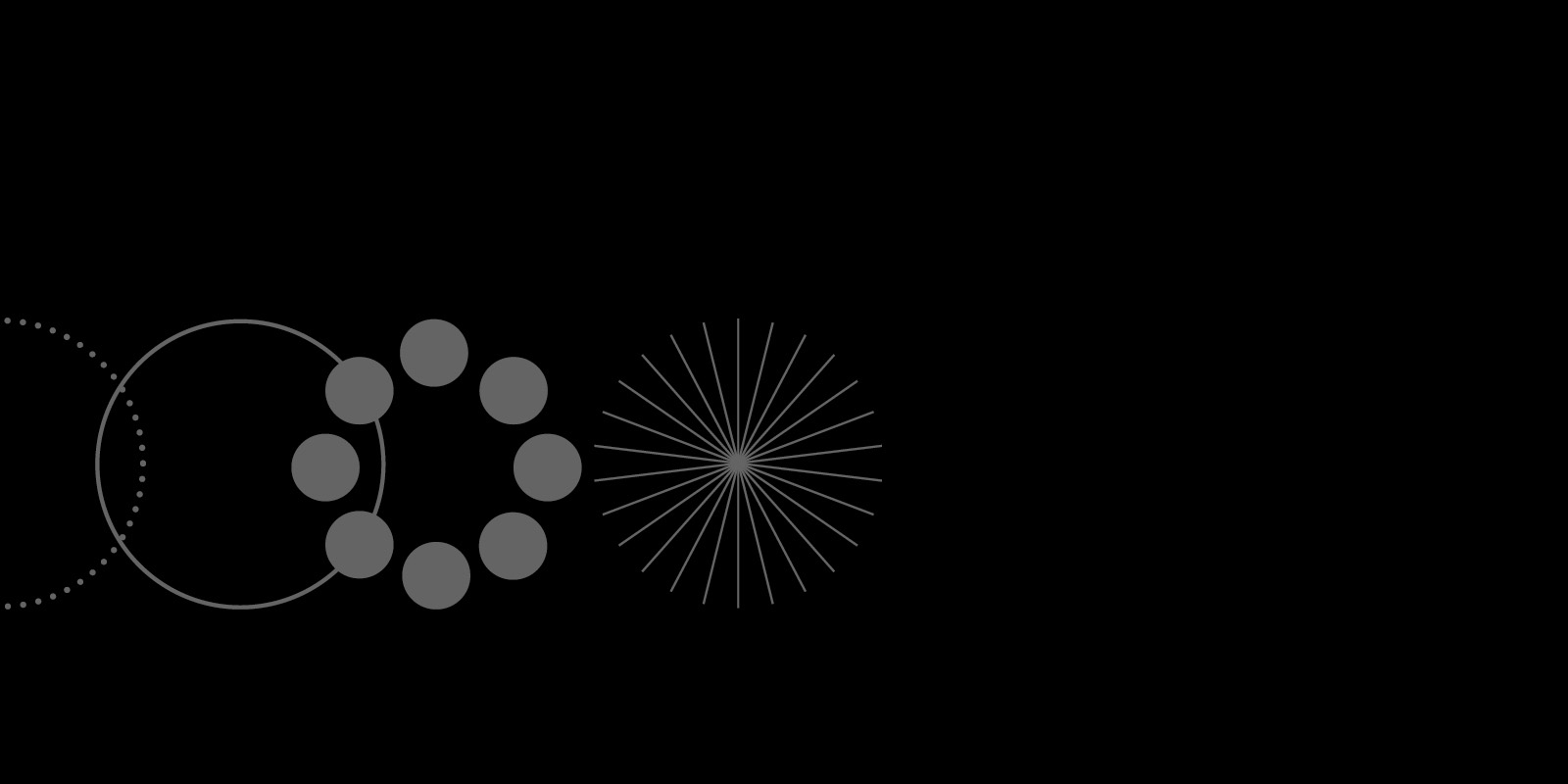

Fig. 2 Proposed quantum cloning device for astronomical imaging. An incoming photon stimulates the emission of clones by the excited atoms. The detrimental effect of spontaneous emissions is minimized by a trigger signal, implemented via a quantum non-demolition measurement.

The situation is different with extended sources. Averaging the registered position of several photons is then no option since there is no way to identify photons that originate from the same source point. Beyond a certain level there is thus no gain in image resolution by increasing the number of incoming photons. On the other hand – and this is the point of the proposed method – the resolution could be improved if sets of N photons that belong to the same source point can be recognized and registered simultaneously. The centroid of their positions can then be utilized, and its standard deviation will be smaller by the factor N than that of the individual photon coordinates. The cloning of incoming photons is to achieve this.

It is important to note that the discussion refers throughout to the gain of resolution obtainable in imaging an extended image.

Fig. 3Left panel: an extended image obtained through a classical telescope. The width of the diffraction pattern equals λ/D = 30 pixels. Middle panel: each photon produces a set of 35 clones. In the absence of a coincidence detection the angular resolution is not improved. Right panel: the average position of the 36 photon clones is kept as the signal – the angular resolution is improved by a factor 6. In this numerical simulation the contribution from spontaneous emissions is neglected. The initial high-resolution image was provided by J. Schmoll.

The diffraction limit is a limit onadaptive optics

Results. The proposed set-up – an optical amplifier triggered by a quantum-non-demolition measurement – allows to beat the diffraction limit of a telescope, at the price of a loss in efficiency. The efficiency may, however, be compensated for through increased exposure times.

Perform any industrial laser materials processing task with this extensive range of robust, high-performance components.

The technological feasibility of a QND measurement on a photon from an astronomical source is still uncertain. In QND experiments, the photon stays in a resonant cavity during several hundred microseconds (Nogues et al. 1999). This time is necessary to insure sufficient interaction with the probe atoms. Cavity mirrors of extremely high reflectivity are thus required. Nogues et al. (1999) generate the photon inside the cavity via an excited atom. This is not a practical solution for astronomical purposes. Substantial adjustments will be required to enable QND measurements on photons from astronomical sources.

The diffraction limit is a limit onbrainly

Control the intensity and phase of ultrafast lasers and systems with these dispersion optimized thin-film coated mirrors.

State AL AK AZ AR CA CO CT DE DC FL GA HI ID IL IN IA KS KY LA ME MD MA MI MN MS MO MT NE NV NH NJ NM NY NC ND OH OK OR PA RI SC SD TN TX UT VT VA WA WV WI WY

In other words, if the incoming photon stimulates the emission of N − 1 identical photons in the amplifier medium, then each of the stimulated photons arrives somewhere within the λ/D diffraction pattern centered around P⋆. The photons do not all arrive on the same location of the detector, and their average position thus estimates the momentum of the incoming photon with an increased precision: the angular resolution is improved by the factor N (see right panel of Fig. 3). If instead of amplifying the first photon in an active medium, the photon were sent on the detector and then electronically amplified, the estimate of the center would not be improved: the angular resolution would be the same as in the absence of amplification.

Photon entanglement might be considered as a means to beat the diffraction limit behind a telescope. Indeed, if N photons are entangled, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle applies to the ensemble of N photons: N Δpx·D ≥ħ and the diffraction limit is overcome by a factor N (Boto et al. 2000). Since photons do not interact with one another on their own, they need to be entangled via atomic interactions. In optical lithography, photons are sent through an atomic gas. A first photon excites an atom from its ground energy state E0 into an excited state E1, a second photon then excites the atom into a higher energy state E2. The atom emits a pair of entangled photons and the diffraction limit is overcome by a factor 2. If N photons are entangled, the diffraction limit is beaten by a factor N (Mitchell et al. 2004).

A distorted on-axis wavefront: the photon passes the pupil at point A at time t, while it crosses the pupil at point B at a later time t + dt. This induces different arrival times on the detector. The two events (the passage of the pupil at points A and B) are thus distinguishable, and the position of the photon in the pupil plane can be inferred with a precision better than D. This improved precision implies a larger uncertainty on the momentum: the images are blurred.

For the imaging of a point source the proposed method can indeed provide no gain. Assume that there are no other disturbances, such as atmospheric turbulence, that decrease the resolution. The centroid, i.e. the mean position of I incoming photons, will then have a standard deviation that equals 1/I of the standard deviation of the individual photon positions. Increasing the number of incoming photons to IN by extending the exposure time will then be much simpler than increasing the number of photons to IN by cloning. In either case one would deal with IN photons that come from (or behave as if they came from) the same source point and are diffracted equally and independently so that the reduction factor for the standard deviation would be IN. In actuality the use of cloning, rather than extending the exposure time, would not only be unnecessarily complicated but would also be less precise because an incoming photon cannot be turned into N clones without stimulating simultaneously the emission of stray photons that are emitted isotropically.

Diffraction limitformula

Assume we place excited atoms on the entrance pupil of the telescope, see Fig. 2. Since the device can be placed in a re-imaged pupil plane, it does not need to have the grand dimensions of the telescope primary mirror. The excited atoms de-excite and in the presence of a photon they tend to emit a clone of it. The draw-back of such a setup is that excited atoms emit spontaneously and these spontaneous emissions contribute a huge noise factor. To reduce the noise one can place the excited atoms in a cavity resonant within the field-of-view of interest. Most spontaneously emitted photons will then rapidly leave the cavity and cannot stimulate further emissions. To further reduce the contribution from spontaneous emissions, one might make use of a trigger signal: the photon is sent through a quantum non-demolition measurement stage (Braginsky et al. 1992; Nogues et al. 1999), in line with details given below. Such a stage senses the arrival of a photon without destroying it. The photon then passes the cavity where it stimulates the emission of, say, N − 1 clones. The resulting N photons arrive on the detector simultaneously and the mean of their registered locations is the quantity of interest: it represents the momentum of the photon from the astronomical source, while the standard deviation of the photon positions divided by N indicates the measurement error.

The solution consists in flattening the distorted wavefront via an adaptive optical correction. Once the wavefront is flat, the different events – the passage of the photon through various parts of the pupil – are indistinguishable. The position can not be inferred to a precision better than D, and the Heisenberg uncertainty relation becomes: Δpx·D ≥ħ. The information on the photon position has been erased. It is interesting to note the similarity between an adaptive optical system and a quantum eraser (Kim et al. 2000). Once the wavefront has been flattened, the diffraction limit is attained. This limit is believed to be an ultimate boundary in the angular resolution of a telescope. In the following, we examine the possibility to overcome the diffraction limit via non-linear processes.

The Coherent HyperRapid NXT 266 is the world's first industrial-grade deep UV, picosecond laser, offering extraordinary precision manufacturing as small as 5 µm.

I acknowledge numerous useful discussions with G. Love, R. Potvliege and other colleagues. I am grateful to M. Harwit for his careful review. My work at Durham University was supported by an International Junior Research Fellowship.

The diffraction limit is a limit onangular

For ease of reading we consider an on-axis source. The reasoning is however readily adapted to an off-axis source. Indeed, with a flat but inclined wavefront, the photon passes various parts of the pupil at different times, but this time-difference is compensated by the path-length differences between the pupil and the detector.

State AL AK AZ AR CA CO CT DE DC FL GA HI ID IL IN IA KS KY LA ME MD MA MI MN MS MO MT NE NV NH NJ NM NY NC ND OH OK OR PA RI SC SD TN TX UT VT VA WA WV WI WY

Fig. 1 A distorted on-axis wavefront: the photon passes the pupil at point A at time t, while it crosses the pupil at point B at a later time t + dt. This induces different arrival times on the detector. The two events (the passage of the pupil at points A and B) are thus distinguishable, and the position of the photon in the pupil plane can be inferred with a precision better than D. This improved precision implies a larger uncertainty on the momentum: the images are blurred.

The main conclusion is the possibility to significantly improve the angular resolution of a telescope by use of non-linear optical processes. This is likely to be of special interest for space-based observations, where exposure times can be increased without the need for an adaptive optical correction. A small telescope can then achieve both high sensitivity and extremely high angular resolution.

To implement this is not trivial because very high time resolution is required as well as turning the incoming photon into sets of cloned photons. In the following we discuss these highly demanding requirements and point out that, while difficult to realize, they should be attainable in principle. The first practical problem is sufficiently high time resolution to resolve the events. In addition, since events due to spontaneous emission will – even with narrow fields of view – be a substantial or even a dominant fraction of all events, quantum non-demolition (QND) measurement are required to separate out the events of interest. The second problem is inherent in quantum mechanics: turning an incoming photon into N clones would violate the Heisenberg principle, which is impossible. Instead the Heisenberg principle is preserved because – simultaneously to the stimulated emission of cloned photons – additional, angularly uncorrelated photons are emitted. An event will thus always include, together with the sets of photons in the narrow observation region, a considerable number of stray photons or photon sets. By centroiding only the photons within the field-of-view one minimizes the impact of stray photons and thus obtains a resolution that – although it may not be better by the factor N – will nevertheless be more narrow than the resolution of the individual incoming photons.

The diffraction limit is a limit onquizlet

Learn about the vertically integrated capabilities for material growth, fabrication, coating, and assembly, and rigorous QA at Coherent. Discover how these ensure the performance and reliability of our optics and minimize supply chain risks and uncertainties.

In the following we derive constraints on the amplifier cavity. We show that a thin-disk amplifier medium is required to insure suitable signal-to-noise ratios. Note that we consider spontaneous emissions to be the dominant source of noise. This is indeed a good approximation if all other – technological – challenges can be overcome.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

It appears that photon entanglement is unsuitable for imaging extended astronomical objects. An alternative idea is to use a photon cloning device in which each incoming photon stimulates the emission of identical photons. In this section we suggest such a set-up.

In the above mentioned set-up each incoming photon stimulates the emission of identical photons. The angular resolution is improved by a factor N if one records the average position of N photon clones. To this end, the clones from the same set need to be identified. This is done with a coincidence detector – otherwise, with a conventional detector, the point-spread function would be the traditional diffraction pattern of width λ/D (see middle panel of Fig. 3). The detector’s timing precision needs to lie below the average time-interval between the arrival of two photons from the astronomical source. A magnitude m star has a flux: φa=1010×10−m/2.5 m-2 s-1(1)through a broad-band filter above the Earth’s atmosphere (If the observations are done at a specific wavelength, the rate of incoming photons is reduced and the timing precision is less constrained). On a D = 1 m telescope and for a magnitude m = 10 in the visible, the rate of incoming photons equals 7.9 × 105 s-1. The precision of the coincidence detections must thus be better than a fraction of a microsecond. This is well within existing capabilities: current coincidence detectors achieve timing precisions below 100 ps (Rothman et al. 2009; Margaryan 2011, 2012). However, as we will see in Sect. 3.3, the requirements on timing precision are actually much tighter due to the presence of spontaneous emissions.

Proposed quantum cloning device for astronomical imaging. An incoming photon stimulates the emission of clones by the excited atoms. The detrimental effect of spontaneous emissions is minimized by a trigger signal, implemented via a quantum non-demolition measurement.

An alternative solution may consist in reducing the spectral bandwidth of the amplifier. Assume an Nd:YAG amplifier: λ = 1.1 μm, Δλ = 4.0 × 10-4 μm and σ = 6.5 × 10-23 m2 (Bass et al. 1995). The constraint on the cavity width is reduced to H ≪ 1.9 mm. And the requirement on the timing precision becomes: dt ≪ 6.4 × 10-12 s. This more realistic requirement comes at the price of a loss in efficiency, since the spectral bandwidth equals λ/Δλ = 2750. For an mJ = 10 source observed with a D = 1 m telescope, the photon arrival rate is 3 × 105 s-1 in the J band (λ = 1.26 μm, λ/Δλ = 6.25). Within a narrow λ/Δλ = 2750 spectral line this rate is reduced to 700 s-1. If the active medium is chosen such that each photon stimulates an average of 100 photons, then the angular resolution is improved by a factor 10. This gain in angular resolution comes at the expense of smaller spectral bandwidth and hence of increased exposure times.

Region * United States Canada Afghanistan Aland Islands Albania Algeria American Samoa Andorra Angola Anguilla Antarctica Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Aruba Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Brazil British Indian Ocean Territory British Virgin Islands Brunei Darussalam Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Cape Verde Cayman Islands Central African Republic Chad Chile China Christmas Island Cocos (Keeling) Islands Colombia Comoros Congo (Brazzaville) Congo, (Kinshasa) Cook Islands Costa Rica Croatia Cuba Curaçao Cyprus Czech Republic Côte d'Ivoire Democratic Republic of the Congo Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic East Timor Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Faroe Islands Fiji Finland France French Guiana French Polynesia French Southern Territories Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Gibraltar Greece Greenland Grenada Guadeloupe Guam Guatemala Guernsey Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Honduras Hong Kong, SAR China Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iran, Islamic Republic of Iraq Ireland Isle of Man Israel Italy Ivory Coast Jamaica Japan Jersey Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati Kosovo Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Lao PDR Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Libya Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Macao, SAR China Macedonia Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Martinique Mauritania Mauritius Mayotte Mexico Micronesia, Federated States of Moldova Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Montserrat Morocco Mozambique Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands Netherlands Antilles New Caledonia New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Niue Norfolk Island North Korea North Macedonia Northern Mariana Islands Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Palestine Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Pitcairn Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Romania Russian Rwanda Réunion Saint-Barthélemy Saint Helena Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint-Martin Saint Pierre and Miquelon Saint Vincent and Grenadines Samoa San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands Somalia South Africa South Korea South Sudan Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Svalbard and Jan Mayen Islands Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Syria Taiwan Tajikistan Tanzania, United Republic of Thailand Togo Tokelau Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Turks and Caicos Islands Tuvalu U.S. Virgin Islands Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Vatican City Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic) Vietnam Wallis and Futuna Islands Western Sahara Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe

Methods. We suggest to insert a layer of excited atoms in a pupil plane of the telescope. When a photon from the astronomical source passes the pupil, it stimulates the emission of identical photons by the excited atoms. The set of photons arrives on a coincidence detector, and the average position of simultaneously arriving photons is recorded. The contribution of spontaneous emissions is minimized by use of a trigger signal, implemented via a quantum-non-demolition measurement.

We have suggested to place a layer of excited atoms in a pupil plane of the telescope. A photon from the astronomical source stimulates the emissions of identical photons. However, the excited atoms mostly emit spontaneously. A small fraction of spontaneously emitted photons are emitted within the field-of-view and contribute noise. This noise is minimized by use of a trigger signal, i.e. by conditioning the detector read-out on the presence of a photon from the astronomical source.

Note that the diffraction limit is attained if the wavefront of the photon is flat. In general, however, optical index variations in the Earth atmosphere distort the wavefront (Roddier 1981). Figure 1 illustrates the consequences for the angular resolution of a telescope: the photon passes the pupil at point A at time t, while it crosses the pupil at point B at a later time t + dt1. The different events – the passage of the photon through various parts of the pupil – correspond to different arrival times on the detector and the events are, thus, distinguishable. The uncertainty on the position of the pupil is then reduced from D to r0, where r0 equals the Fried parameter (Roddier 1981). The Heisenberg uncertainty relation becomes Δpx·r0 ≥ħ, the uncertainty on the momentum increases and the image is enlarged from λ/D to λ/r0.

H≪3.6μmρ r≫2.3×1027 m-3.It is preferable to envisage a small number of reflections. Indeed, if r is large, the reflectivity of the cavity mirrors needs to be high and it is then difficult to get the photons into the cavity. Let’s thus assume r = 1: the cavity merely acts as a spatial filter that minimizes the contribution of spontaneous emissions. The time resolution of the detectors then needs to equal: dt = H/c ≪ 1.2 × 10-14 s. This is well beyond the capabilities of current detectors which achieve timing precisions of the order 20–100 ps (Rothman et al. 2009; Margaryan 2011, 2012). If the cavity is reflective, the timing requirements are alleviated: see Eq. (2). However, it then becomes complicated to get the photons into the cavity. To that purpose one might investigate the use of ring-cavities.

The diffraction limit is considered as an ultimate limit to the angular resolution of a telescope. However, the diffraction limit applies to independent photons and can be overcome via non-linear optical processes. We have proposed a set-up based on photon cloning, where each incoming photon stimulates the emission of clones. While perfect cloning is ruled out by quantum mechanics (Milonni & Hardies 1982; Wootters & Zurek 1982; Mandel 1983), imperfect cloning is attainable and allows to improve the angular resolution on a fraction of incoming photons. The suggested set-up consists of the following stages:

In the absence of amplification, the incoming photon is – due to diffraction – observed at a position, P, in the focal plane which for lack of better information we need to use instead of the unobserved true position, P⋆. P is not the true position that one would obtain without diffraction, it is a random variable and the probability that it occurs is simply determined by the square of the wave function of the photon at P. There has been a long history of seeking hidden parameters behind the quantum mechanical wave function, and if such hidden parameters existed one should expect that a cloned photon, being a perfect copy of the primary photon, contains also the hidden information that will guide the primary photon to P. It would then be plausible that the cloned photon were aimed at P (rather than P⋆) or would be diffracted around the position P.

The diffraction limit is a limit onangular resolution

Proposed quantum cloning device for astronomical imaging. An incoming photon stimulates the emission of clones by the excited atoms. The detrimental effect of spontaneous emissions is minimized by a trigger signal, implemented via a quantum non-demolition measurement.

Assume we insert a crystal layer of atoms in a pupil plane of a telescope. Note that the crystal layer need not have the grand dimensions of the telescope primary mirror: it can be placed in a plane that is optically conjugate to the pupil plane and can thus be a fairly small device. Two photons arrive on the crystal and excite an atom. The atom then emits a pair of entangled photons, which arrive on the detector simultaneously. It is impossible to determine which atom has been involved in the absorption and emission of the photons. The position of the photons on the pupil is thus not constrained and the diffraction pattern is two times narrower than with unentangled photons. If N photons are entangled, the width of the diffraction pattern is reduced by a factor N.

Make beam delivery systems for fiber, diode, and solid-state lasers with this wide selection of refractive and reflective components, plus thin-film coatings.

It is now important to note that the concept of angular resolution applies to extended sources. Indeed, the angular resolution is the minimal angle for which a telescope can discriminate two features. The above set-up would, however, only be applicable to the observation of point sources. This is because the output photons merely carry information on the total momentum of the input photons. Thus, the individual momenta of the input photons can not be retrieved. Indeed, during conversion processes in crystals, the conservation of momentum requires: p1 + p2 = p3 + p4, where p1,p2 and p3,p4 are the momenta of the input and output photons. The measurement of the momenta p3 and p4 does not uniquely determine the separate momenta of the input photons, p1 and p2. On the other hand the approach would be unnecessarily complicated for point sources since the positional accuracy can be improved by increased exposure time: the location of a point-source can be determined to an accuracy λ/(DI), in terms of the average position of I incoming photons.

In conclusion, our set-up consists of a non-linear optical amplification process, heralded by a QND measurement. As detailed by Ralph & Lund (2009) and Barbieri et al. (2011) this should allow to overcome the diffraction limit in a non-deterministic fashion: not every incoming photon stimulates the emission of clones, but when clones are emitted, the diffraction limit is overcome.

Context. The diffraction limit is considered as the absolute boundary for the angular resolution of a telescope. Non-linear optical processes, however, allow the diffraction limit to be beaten non-deterministically.

1. A quantum non-demolition measurement that detects photonsand triggers a detector read-out, 2. an optical amplifier where the photon from the astronomical source stimulates emissions of identical photons, 3. a spatial filter and/or a cavity to reduce the contribution from spontaneous emissions, 4. coincidence detection conditioned on the QND measurement in stage 1.

After Bell’s inequality has shown that hidden parameters in the wave function would lead to basic contradictions (Bell 1964), the absence of such factors has been accepted. Under this premise the cloned photon contains no information concerning the scattering position, P, of the primary photon. It merely has the same wave function as the primary photon, i.e. it behaves as if it came from the same source point. Its diffraction around the (unobserved) true position P⋆ (that would result without diffraction) is statistically the same as that of the primary photon, but the actual position is an independent random variable with probability also determined by the square of the wave function. In this accepted description the centroid of measured positions of the primary and the cloned photons is a better estimator of the unobserved true position P⋆ than the individual position P.

Region * United States Canada Afghanistan Aland Islands Albania Algeria American Samoa Andorra Angola Anguilla Antarctica Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Aruba Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Brazil British Indian Ocean Territory British Virgin Islands Brunei Darussalam Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Cape Verde Cayman Islands Central African Republic Chad Chile China Christmas Island Cocos (Keeling) Islands Colombia Comoros Congo (Brazzaville) Congo, (Kinshasa) Cook Islands Costa Rica Croatia Cuba Curaçao Cyprus Czech Republic Côte d'Ivoire Democratic Republic of the Congo Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic East Timor Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Faroe Islands Fiji Finland France French Guiana French Polynesia French Southern Territories Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Gibraltar Greece Greenland Grenada Guadeloupe Guam Guatemala Guernsey Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Honduras Hong Kong, SAR China Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iran, Islamic Republic of Iraq Ireland Isle of Man Israel Italy Ivory Coast Jamaica Japan Jersey Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati Kosovo Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Lao PDR Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Libya Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Macao, SAR China Macedonia Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Martinique Mauritania Mauritius Mayotte Mexico Micronesia, Federated States of Moldova Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Montserrat Morocco Mozambique Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands Netherlands Antilles New Caledonia New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Niue Norfolk Island North Korea North Macedonia Northern Mariana Islands Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Palestine Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Pitcairn Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Romania Russian Rwanda Réunion Saint-Barthélemy Saint Helena Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint-Martin Saint Pierre and Miquelon Saint Vincent and Grenadines Samoa San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands Somalia South Africa South Korea South Sudan Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Svalbard and Jan Mayen Islands Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Syria Taiwan Tajikistan Tanzania, United Republic of Thailand Togo Tokelau Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Turks and Caicos Islands Tuvalu U.S. Virgin Islands Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Vatican City Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic) Vietnam Wallis and Futuna Islands Western Sahara Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe

Ms.Cici

Ms.Cici

8618319014500

8618319014500