Getting to the Truth Faster; Axon Partners with iNPUT-ACE ... - input ace

Push-Stun Mode – Pressing or pushing an activated CEW onto a subject's body, allowing electrical energy to be transferred to that individual.

Incident types have been reorganized in Table 10 to illustrate descending deployment probabilities. There are clearly a wide assortment of likelihoods, ranging from 100% for CEW‑related cases involving "murder or attempted murder", over 50% for both "assault on a police officer" and "obstruction", and less than 10% for "driving while intoxicated", "disturbing the peace" and "kidnapping".

In 8 (12.3%) cooperative incidents, the subject became immediately cooperative after a CEW was unholstered and a warning issued by police.

First, there are a number of variables that are not collected as part of the SB/OR Reporting System and are no longer available for consideration. Second, there are new variables that have been added that were not part of the RCMP's previous CEW forms. Third, there are certain variables that have the same name but have changed in terms of their meaning. In some cases, the changes have been relatively minor; for example, in Table 2 (see Appendix 2), the Setting variable now includes a category for "Indoor and Outdoor". In other instances, however, the modification may have a greater impact on the recording, reporting and interpretation of the data; for instance, the variables Substance Use (Table 3 in Appendix 2) and Possession of a Weapon (Table 4 in Appendix 2) both are now preceded by the word Perceived. And, finally, the variable Incident Type has changed so dramatically that it is no longer comparable across reports. Under the RCMP's previous CEW reporting system, Incident Type was task-oriented; however, under the new SB/OR system, Incident Type is now based on the nature of the offence that precipitated contact between police and the subject.

Part One provides readers with contextual information with respect to: (a) the genesis and evolution of the Commission's work related to the CEW; (b) the RCMP's Incident Management / Intervention Model (IM/IM); (c) the RCMP's SB/OR Reporting System, which captures data and information pertaining to CEW usage by its members; and (d) the CEW itself.

3.1.5. Multiple deployment or continuous cycling of the CEW may be hazardous to a subject. Unless situational factors dictate otherwise, members must not cycle the CEW for more than 5 seconds on a subject and will avoid multiple deployments.

With respect to CEW Occurrence Characteristics (Figure 25 and Table 28 in Appendix 2), there was some minor shuffling evident in the distribution of CEW reports across RCMP divisions. The most notable change was the drop of almost 10 points in the proportion of cases recorded in British Columbia. The largest corresponding increases occurred in Saskatchewan and Alberta, but only the gain in Saskatchewan was statistically significant. The figures for British Columbia and Saskatchewan are, respectively, a historical low and high. The results for Duty Type, particularly for "General Duty", appear, at first glance, to be quite different between 2009 and 2010. However, this divergence is likely the result of the considerable number of missing cases in 2009 compared to no missing cases in the current reporting year. If one looks only at "known" cases, the figure for "General Duty" in 2009 rises to 94.6%, a finding comparable to 2010. Similarly, controlling for missing cases, Constables account for 91.1% of CEW reports in 2009; this is an equivalent percentage to 2010.

In addition to providing descriptive statistics and exploring significant bivariate relationships, an important goal of the present report is to highlight on-going changes in the manner in which CEWs are employed by RCMP members in the field. This section analyzes historical, yearly change in two ways. First, the results from 2010 are compared with those of 2009. And, second, an examination of specific variables over a time period from 2002 to 2010 is undertaken to identify longitudinal patterns in CEW use. The results of these two sets of analyses are presented below.

Members were called to an incident where a male was stabbed by his wife. The wife was still reported to be at the location and the victim was unconscious. When members arrived, the subject was located in the bathroom. The door was locked and she would not open it. There was a sheet covering a hole on the door. One member ripped the sheet down and found the subject sitting on the toilet crying. A CEW was drawn and displayed to the subject, as the one-plus-one rule applied. Members believed that the subject was emotionally disturbed at the time. When asked to come out, the subject refused and continued crying. Eventually, through verbal intervention and de-escalation, the subject surrendered and members were able to restrain her.

Push-stun mode is primarily used in actively combative or assaultive situations where RCMP members cannot achieve separation from the subject, as in the following case.

The RCMP's divisional rankings were also consistent with those of the previous year. With the exception of the Yukon, which rose from 10th in 2009 to 7th place, no province or territory moved more than two spots in the 2010 rankings. In terms of proportions of CEW reports, the largest drop (9.3%) was recorded in British Columbia. Very small drops were also present in Newfoundland and Labrador, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and New Brunswick. Conversely, the proportion of reports attributable to Saskatchewan increased by 4.5 percent. Modest increases were also found in Nova Scotia, Alberta and Manitoba. A comparison of 2009 and 2010 figures is presented in Table 28 (see Appendix 2).

Information regarding injuries is sparse within the SB/OR Reporting System. The description of injuries that was previously available through the RCMP's CEW usage reports has, unfortunately, been discontinued. In its place are, arguably, less illuminating questions.

And, lastly, the Weapon Model section of Table 4 (Appendix 2) highlights the ongoing phasing‑out of the Taser® M26 by the RCMP. In 2010, the M26 model was used in only 10% of events.

6.2.2. To make changes or additions after submission of an SB/OR report, unlock the SB/OR report and have the submitting member make the required changes or additions and resubmit. Attach a copy of the revised report to the operational file in addition to the original report to ensure changes are tracked.

5.2. Whenever possible, in medically high risk situations, request medical assistance before using the CEW. If medical assistance is not requested or a CEW deployment is necessary before the arrival of medical assistance, obtain medical assistance as soon as practicable.

Figure 39b (see also Table 39) shows that the total number of CEW cartridges deployed has steadily declined since 2008. Perhaps more importantly, the graph reveals a long-term trend that CEWs are more apt to be cycled only once as opposed to two or more times. In terms of the proportion of cycling, 2010 marked an all-time high for cycling the device once and a record low for two cycling, and for three or more cycling.

By comparison, the results for Emotionally Disturbed show a simple, direct effect: CEW engagement is more likely when the subject is deemed emotionally disturbed (Figure 23 and Table 13 in Appendix 2).

Part Six examines both quantitative and qualitative analyses of the narrative summaries provided in the RCMP's CEW-related SB/OR reports, offering greater context around the circumstances of CEW usage by the RCMP in 2010.

6.1.8. If a CEW is unintentionally discharged, report the incident to your supervisor and record the details in your notebook.

A search of the residence was completed and the subject was located in the basement. The subject was hiding underneath a mattress and was ordered to come out. The CEW challenge was given and lethal over-watch maintained. The subject cooperated, the CEW was not deployed, and the subject was handcuffed. The CEW was immediately holstered and not brought out again.

Due to the relatively small number of cases involving youth, considerable care must be taken in interpreting even the descriptive results. Still, there were several notable differences when "youth cases" were compared to the overall results.

The average number of usage reports per RCMP member remained virtually unchanged between 2009 (1.26) and 2010 (1.24) (Figure 27).

While the analyses offered in the previous section are appropriate for comparing more recent changes from 2009 to 2010, they are not able to discern potentially important long-range trends. This section attempts to identify and evaluate important historical trends in relation to the comparisons examined in Section 5A above.Footnote 19

Figure 37 (see also Table 37) reveals that, with minor fluctuations, the percentage of events where push-stun mode was used more than once was relatively consistent at about 37% between 2003 and 2005. The following two years experienced a slight increase in usage, followed by a sharp decline in 2008. Percentages in 2009 and 2010 seem to reflect the earlier trend in push-stun mode deployment observed in the 2003 to 2005 time period. This trend seems, at least in part, to reflect ongoing shifts in the manner in which RCMP members use CEWs. As stated previously, because push-stun mode is appropriate in very close encounters, its use is generally not optimal for officer safety. Thus, use is limited to more exigent circumstances when probes cannot be effectively used.

Conducted Energy Weapon (CEW) – A device that delivers high voltage, low current, shocks to a subject, designed to cause temporary incapacitation through involuntary muscle disruption or pain compliance. Also referred to as a conducted energy device (CED), electronic control device (ECD), stun gun or TASER®.

For example, the subject may have been injured in the altercation that led to the CEW being deployed. In general, however, the narrative summaries extracted from the RCMP's SB/OR Reporting System suggested that the medical exams were primarily related to the CEW.

Finally, there were 15 miscellaneous grievous bodily harm or death cases found in the CEW reports extracted from the SB/OR Reporting System.

The subject initially refused to cooperate with the members' directions to remain inside the residence. When the subject was physically restrained with soft hand control to prevent him from walking outside, he became instantly combative and assaultive. The subject reared and bucked his body while continuing a barrage of obscenities and verbal abuse. After several more members arrived to assist in holding the subject back, he began to fight by kicking his legs, rearing his body and bucking back. The subject was forced back into the residence and the tussle ended with the subject on the stairs on his stomach. Members were still unable to restrain the subject, and member no. 1 announced to fellow members that she had a CEW. Member no. 1 removed the CEW from its holster. The subject was warned that she had a CEW and that if he did not stop fighting it would be used. The subject did not stop his behaviour and instead fought back even harder. Member no. 1 removed the cartridge from the CEW, positioned herself among the other members present, and yelled out "Taser." Member no. 1 deployed the CEW in push-stun mode against the subject's back. After the first deployment, which was held against the subject for half of the cycle, the subject resumed his assaultive behaviour and would not become cooperative or compliant. Member no. 1 deployed the CEW a second time. This time, the subject indicated that he would stop resisting. Several other members were then able to handcuff the subject.

In the vast majority (85.5%) of cases, RCMP members judged the CEW to have been effective in controlling subjects (Table 4 in Appendix 2). It should be noted that since this is a new question, there is no basis for direct comparison with previous CEW annual reports published by the Commission. However, this figure is consistent with previous questions that asked whether the CEW "avoided the use of lethal force" or "avoided injuries". The variable Impediments captures the circumstances in which the CEW was not considered effective. Approximately one‑quarter of ineffective deployments were owing to the CEW having no effect on the subject. Secondary analyses found that all those subjects not affected by the CEW were under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol. Although several potential response categories are available, the large proportion of "other" impediments suggests that the reasons for the CEW having been ineffectual were extremely diverse.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) responds to approximately 7,000 calls for service each day, or more than 2.5 million annually (RCMP, 2010a: 37). There are situations, however, where police officers are required to use force to achieve a lawful objective (e.g. making an arrest, acting in self-defence or protecting others). The Criminal Code authorizes such force as long as it is reasonable in the circumstances.

As noted in the Background section of the report, the Incident Type variable reported in Table 1 (see Appendix 2) has changed considerably when compared to the Commission's previous annual CEW reports. As a result, it will be difficult for readers to make year-to-year comparisons.

In a typical tactical case, RCMP members are called to a scene where the subject has, according to the information available, committed a serious or violent crime (often common or spousal assault) or is threatening same (usually with a weapon). In cooperative cases, members were able to serve the warrant or resolve the situation without resistance of any kind. In both of the following examples, the CEW was drawn before the subject was encountered.

In 27 CEW incidents (14.1%) in 2010, grievous bodily harm was inferred from "non‑compliance with additional circumstances", such as the refusal to show hands, a weapon in plain view, the presence of a possible weapon, or threat cues. There is no clear indication as to how these cases differed from similar "non-compliance with additional circumstances" that were classified as active resistant. In these cases, there seems to have been a degree of subjectivity or difference in interpretation on the part of the RCMP member.

Chi-square is not the most appropriate statistical technique for evaluating longitudinal relationships, but the cross‑tabulations that underlie the technique are very effective in illustrating trends. More sophisticated statistical techniques (i.e. mixed effects logistic regression models) were used to validate the chi-square results.

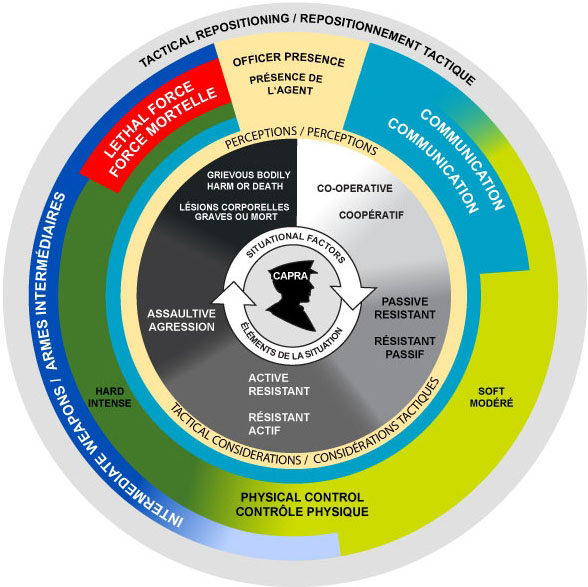

To assist its members in deciding (and explaining) when, where and what kind of intervention strategies to use in managing incidents, the RCMP developed the Incident Management / Intervention Model (IM/IM). Essentially, the IM/IM represents the process or framework by which RCMP members assess, plan and respond to situations that threaten public and/or officer safety through justifiable and reasonable intervention.

Axon Academy

9.1.3. Testing of the CEW will determine the working state of the CEW and whether the weapon is functioning as per the manufacturer's specifications.

Members responded to a complaint of an intoxicated male who had broken the window of his mother's residence. The members located the subject of the complaint in the rear yard of the residence. In his hands were an axe and a machete. He was instructed to drop his weapons and come towards the police. He turned and walked into a shed in the rear yard. RCMP members approached and he came out of the shed with the axe and machete still in his hands. He was ordered several times to drop the weapons. A CEW challenge was issued while lethal force over-watch was provided by other members at the scene. The subject still did not drop the axe or machete and the CEW was deployed in probe mode. He then dropped the weapons and fell to the ground.

It is important for readers to note that all of the following analyses were limited to circumstances in which the CEW was actually deployed.

The member saw a male running out of the house and told him to stop, as he was under arrest. The command was given again to the subject at which point he stopped and began walking towards the officer with his fists clenched and raised. He was staring at the officer and appeared to be assaultive. The member drew the CEW from the holster and turned it on while ordering the subject to stop and get on the ground. The CEW was pointed at the subject using the laser sight to aim at mid-torso. The subject saw the CEW being pointed at him and repeatedly told the officer to shoot him. The member told the subject to stop and the subject charged at the officer. The CEW was deployed at the subject's mid-torso area. The CEW had a momentary effect on the subject, but then the subject continued to walk towards the member and began swinging his arms to break the wires from the CEW.

My Axon

Another 24 events (12.5%) involved "tactical" conditions. In some cases, the seriousness of the tactical approach was heightened by the circumstances of the call, including the subject's recent actions, and his or her criminal/violent history.

3.1.4. Where tactically feasible, members will issue a verbal warning so the subject is aware that a CEW is about to be deployed.

The findings for cycling presented in Figure 38 (see also Table 38) display a similar stable pattern between 2003 and 2009. However, 2010 marks a notable break in this historical trend, falling to a rate of 8.6%. In other words, in the current reporting year, fewer than 10% of CEW events resulted in multiple cycling of the device. It is difficult to speculate as to the cause of this drop. Further data will be required to determine whether the 2010 result for multiple probe cycling is merely an anomaly or represents a substantive change.

Part Seven looks at two special populations that the Commission has identified as being at risk: youth aged 13 to 17, and subjects identified as being mentally ill.

Overall, the number of CEW occurrences dropped by 14.2% in 2010Footnote 9. In terms of a breakdown by RCMP jurisdiction, the number of CEW reports: increased in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Nova Scotia; decreased in the Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, British Columbia, National Headquarters, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island; and remained constant in Alberta, Ontario, the National Capital Region and Quebec.Footnote 10

As Figure 1 illustrates, the IM/IM is not considered to be a "use of force continuum", nor does it imply a linear path of use of force by police. Rather, the circular representation of the model infers that any level of intervention is available to the member, at any time, in order to effectively manage the suspect's corresponding level of resistance and account for situational factors and risk as assessed and perceived by the member. The IM/IM framework has the RCMP's problem-solving model known as CAPRA (Clients/Acquire and Analyze/Partnerships/Response/Assess) as its focal point (RCMP, 2011).

Part Two presents descriptive analyses of CEW-related SB/OR reports completed by RCMP officers between January 1 and December 31, 2010. The various analyses have been organized in a way so as to correspond, as closely as possible, with the various categories found in the SB/OR system.

Members were called to a bar fight and a male suspect was seen leaving the bar. The subject managed to elude the police, while members continued to search for him. The subject had reportedly broken a beer bottle over another person's head and then left the scene. A short time later, a male matching the description of the subject was seen walking back in the direction of where the fight had taken place, with a golf club in hand. Members approached and placed the subject under arrest. The subject then fled from the members. A further search for the subject was done and he was located on the front deck of his home. The subject called on the members and stated that there would be a fight if they tried to arrest him. The subject then threatened to shoot the members with a 9mm handgun and stated that they would have to take him out if they wanted to arrest him. The subject could be seen standing in his doorway but would not show his hands to the members. The subject was very belligerent with the members and would not show himself completely. The subject was believed to have just assaulted a person with a weapon, was seen carrying a golf club back in the direction of the fight, and fled police when confronted. The subject was continually aggressive towards the members and repeatedly stated that if approached, he would fight or shoot the members. The subject eventually retreated back into the residence. Member no. 1 gained a vantage point at the front of the house while member no. 2 maintained lethal over-watch. The door opened and member no. 1 heard what he believed to be a shot from a firearm. The other members immediately used trees and anything they could for cover. Member no. 1 heard another sound, very much like the first sound, and saw the subject standing in the doorway. At this time, however, member no. 1 could not confirm whether the subject had a weapon in his hands. Given the violent nature of the assault to begin with, and the threats uttered by the subject at members, member no. 1 deployed the CEW to prevent the subject from accessing any other weapons and to prevent any injury to members, as the subject had now escalated the incident to either shooting at members or at least throwing objects at them to try and injure them. After the subject was taken into custody, it was discovered that the subject had been throwing golf balls at the members.

The RCMP received a complaint that a man had broken into a residence through the kitchen window. The complainant stated that the subject was violent and intoxicated, but did not know if weapons were involved. After talking to the complainant on scene, the member determined that the subject had committed break and enter. Due to the fact that the complainant was upset and believed that the subject was violent, the member feared grievous bodily harm, or even possibly death, to all involved and, as such, decided to use his/her CEW to clear the residence. The member did not know if the subject was armed with a weapon or not, nor did he/she know his state of mind or ability to harm another. The member believed his/her CEW to be the most effective, least harmful, intervention tool at the time. The member entered the residence after taking his/her CEW out of its holster. The member announced RCMP presence and went down the steps of the basement. The member announced police presence again and ordered the subject to come out. There was a small central room with three closed doors from it. The member threw open the first door, announced RCMP presence, and cleared the small furnace room from the doorway. The member repeated this sequence for the next door. The third door opened and a male stepped out. The member trained the CEW upon him and ordered him to step out to the middle of the central room and to kneel upon the floor. The member kept the CEW in the low-ready position until member no. 2 had the male under control in handcuffs. Member no. 2 removed the subject from the residence while the other member cleared the remaining rooms in the basement. At this point, the member re-holstered his/her CEW.

For 2009 and 2010, the RCMP's "A" Division (National Capital Region), "C" Division (Quebec), and "O" Division (Ontario) did not generate any CEW reports.

As has historically been the case, a large proportion of CEW reports were generated by the western provinces in 2010. Together, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba contributed about 80% of all reports. This percentage was approximately the same as last year's figure (78.5%). While British Columbia produced more reports than any other province, the comparative gap was much less significant than it has been in the past. In 2009, the RCMP in British Columbia created 1.86 times as many reports (in terms of CEW usage) as the next closest province, Alberta. By comparison, the ratio was only 1.19 in 2010.

As an intermediate force option, one of the goals of CEW usage is to de-escalate increasingly serious situations, thus avoiding the need for lethal force. This section of the report examines CEW attempts to de-escalate subject behaviour. It considers only incidents in which the CEW was drawn but not ultimately deployed, as deployment is taken as de facto evidence that the CEW did not function as a mechanism of de-escalation. This is not to say that the CEW should never be deployed, as CEW deployment can effectively resolve an incident in many cases. But, in terms of de-escalation, engagement does not represent a positive outcome. De-escalation also considers only those behaviours categorized as passive resistant or higher. After taking these considerations into account, the results in this section are based on 352 cases.

Another significant form of assaultive behaviour in 2010 CEW incidents consisted of threat cues (77 cases, or 32.1%). Threat cues are prompts or warning signals that RCMP members recognize as precursors to more aggressive behaviour. Threat cues included such things as adopting a bladed or boxer's stance, intense staring, the clenching and unclenching of fists, and noticeable body tensing. In many cases, threat cues were exacerbated by closing the distance. In other words, these behaviours became even more worrisome when the subject began to move toward the officer. Earlier, it was noted that non-compliance coupled with threat cues was sometimes identified as being actively resistant. However, it is much more commonly classified as assaultive.

In contrast to the above, approximately two-thirds (66.4%) of all RCMP members across Canada who were CEW-certified in 2010 were serving in British Columbia (465 members), Alberta (646 members), Saskatchewan (505 members) or Manitoba (383 members) (Baldwin and Lackie, 2011: 30).Footnote 11

Moreover, while the decrease in the average number of cycles was not large, it was nevertheless statistically significant (Figure 32a and Table 32 in Appendix 2). Specifically, 2010 experienced far fewer cases of the CEW being cycled two or more times.

As demonstrated in Figure 18a (see also Table 6 in Appendix 2), results show that only a small number (3.5%) of subjects were injured by CEW usage in 2010. Puncture marks which are characteristic of probe deployment are not considered by the RCMP to constitute injury. Subjects who were injured were almost always (91.3%) offered medical attention, and most of those who were offered medical treatment accepted. RCMP members were treated for injuries in only a fraction (1.4%) of CEW-related cases.

In push-stun mode, the device is pressed against the subject and a charge is delivered through small, non-penetrating probes. In probe mode, two small barbs with wires attached are ejected from the CEW and embedded into the subject's skin or clothes; an electrical charge is then delivered through the wire tethers.

Among the most significant changes to the SB/OR Reporting System is its increased emphasis on capturing subject behaviour. Figure 11 (see also Table 4 in Appendix 2) presents several of these subject-oriented variables. The general categorization of subject behaviour indicates that most subjects (84.7%) encountered by RCMP members in CEW incidents were at least actively resistant. More specifically, 18.8% of subjects were deemed Actively Resistant, 36.6% were thought to be Assaultive and 29.3% displayed behaviour consistent with the intent to cause Grievous Harm or Death (10% of subjects involved in CEW incidents were considered Cooperative).Footnote 14

For the purpose of illustration, we begin by testing the association between CEW Deployment and Substance Use (Figure 19 and Table 7 in Appendix 2). In this case, both variables were measured dichotomously as in "yes" or "no". That is, the CEW was either deployed or it was not, and substance use was either perceived by RCMP members to be involved or it was not. The proportion of "yes" answers for CEW Deployment is of particular interest here. Figure 19 shows that when substance use was not involved, the CEW was deployed 22.9% of the time. However, when substance use was manifest, the proportion of cases in which the CEW was deployed rose to 35.3%. The chi-square statistic of 8.24 (at one degree of freedom [df]) is significant (p < 0.05). Thus, we can conclude that substance use was related to CEW usage and that it significantly increased the probability that the CEW was deployed by RCMP members.

As has commonly been the case in the past, in 2010, the vast majority of CEW reports were filed by General Duty (96.5%) RCMP members with the rank of Constable (91.1%) (figures 3 and 4; Table 1 in Appendix 2). This is expected given that the majority of the RCMP's front-line members are uniformed constables.

Member no. 1 located a male in the north parking lot sitting alone in a gazebo. Member no. 1 observed that the male matched the description given by the complainant: dressed all in black, wearing a toque. Member no. 1 requested that member no. 2 attend his location to speak with the male. Members no. 1 and no. 2 approached the male in the gazebo. The male stood up from the bench and walked out into the parking lot. Member no. 1 told the male to stop advancing. Member no. 2 asked the male what his name was, but he did not respond. Member no. 2 subsequently asked him three times, but the male would not speak. Member no. 2 could see that the male was starting to tense up his body and become agitated. Member no. 1 commanded the subject to his knees. Member no. 2 pulled out his CEW to cover member no. 1 as he advanced on the subject. Member no. 1 was able to guide the subject to the ground without injury.

In addition to the general query regarding the behaviour exhibited by the subject, the SB/OR Reporting System also asks RCMP members the following question: Based on your assessment, did you perceive a threat from the subject that was greater than the behaviour being displayed during this event? In almost half of all cases (and two-thirds of cases if "Grievous Harm or Death" is excluded, as perceived greater threat does not apply), RCMP members noted that there was some factor (or combination of factors) that elevated situational risk (Figure 12a).

RCMP training warns against the over-use of the CEW as a means of compliance. Members are instructed to assess the appropriateness of CEW use based on the ineffectiveness of, for example, officer presence, communication skills, police instructions/commands, or direct physical attempts at control without a weapon, and the subject's threat/behavioural level as represented in the RCMP's IM/IM. In fact, RCMP CEW training evaluates whether the weapon was properly used taking into account, among other things, the degree of communication between the officer and the subject before, during, and after the incident, and whether de-escalation tactics were considered prior to the deployment of the weapon. Reinforcing this practice, section 3.1.3 of the RCMP's Operational Manual on CEWs states that "[w]here tactically feasible, members will use de-escalation techniques and/or other crisis intervention techniques before using a CEW." Likewise, the Braidwood Commission on Conducted Energy Weapon Use (2009: 19) recommended that:

Braidwood Commission of Inquiry on Conducted Energy Weapon Use (2009). Restoring Public Confidence: Restricting the Use of Conducted Energy Weapons in British Columbia. Vancouver, British Columbia: Braidwood Commission of Inquiry on Conducted Energy Use.

Figures 39a and 39b (see also Table 39 in Appendix 2) present data at the Force-wide level. Again, Figure 39a illustrates the long-range trend of declining deployment rates since 2005 and the corresponding increase in the CEW being used as a tool of deterrence, particularly as of 2008.

6.3.3. Maintain a sign out log form 6333 for each CEW assigned to the unit by recording the time, date and name of each member signing out a CEW.

Members were executing a warrant at a residence. The residence was well known to members as a location where alcohol was purchased and consumed. Members had reason to believe that there was a possibility of numerous intoxicated subjects being present. Members approached the residence, knocked on the door, and announced: "Police Search Warrant." This was said a number of times. There was no response from within the residence and at this point members used force to kick down the door. Member no. 1 entered the residence with his CEW drawn, activated and at the low-ready position. Member no. 1 entered the dwelling and located the suspect. Members were able to clear the residence with no injuries to the police or the public. The suspect complied with members' directions and demonstrated cooperative behaviour before, during and after the search with no change in behaviour.

The types of events that typically lead to CEW usage tend to result in more than one police officer responding to the call. On average, 3.1 RCMP members were present at CEW-related incidents in 2010 (Figure 5; Table 2 in Appendix 2). This is a slight increase from the previous year's figure of 2.8 members (see Table 29 in Appendix 2).

It was dark in the residence. Members approached the subject, who was face down with his hands hidden. Member no. 1 kept the CEW trained on the subject while member no. 2 went hands-on to arrest the subject. The subject became highly resistant at this time. Member no. 1 issued the CEW challenge, but the subject did not respond. Eventually, member no. 1 re-holstered the CEW and assisted member no. 2 in getting the subject's hands out from under his body and placing him in handcuffs.

Placed in historical context, the increase in the mean number of CEW reports per RCMP member involved in a CEW incident in 2010 is not as unusual as it first appears (Figure 34 and Table 34 in Appendix 2). Rather, 2009 was a somewhat anomalous year in terms of the number of RCMP members with multiple reports. The 2010 value of 30%, while still the highest recorded, is more comparable to the values reported between 2006 and 2008.

6.4.1. Ensure that supervisors as well as Divisional Use of Force Coordinators/delegate review all SB/OR reportswhen a CEW was used as soon as possible after they are completed for adherence to applicable directives.

In very rare cases, RCMP members either threaten the use of a CEW or actually deployFootnote 2 a device as an intervention option to control a subject. In June 2011, the RCMP provided the Commission for Public Complaints Against the RCMP (Commission) with 2010 CEW data from its Subject Behaviour / Officer Response (SB/OR) Reporting System. The present report, comprised of 9 sections,Footnote 3 provides the results of analyses conducted by the Commission pertaining to the RCMP's use of the CEW in calendar year 2010.

With respect to Incident Type,Footnote 12 the three most common incidents involving CEWs in 2010 were Assault (25.8%), Mental Health (15.4%) and Assault on a Police Officer (12.7%). By aggregating the various sub-categories of assault (i.e. assault, sexual assault, and assault on police and other peace officers), all assault-related incidents represented approximately two in every five occurrences (39.2%). And, as demonstrated in Figure 2 and Table 1 (see Appendix 2), the remaining incidents were spread across a wide variety of offences and circumstances.

4.1. Only candidates taking the CEW User Course or the CEW Instructor Course or the Cadet Training Program are permitted to participate in the CEW Voluntary Exposure Exercise. Any such exposure is to be done under the direct supervision of an RCMP CEW Instructor.

Following these reports, the Commission began to systematically analyze the RCMP's use of the CEW on a yearly basis. The first report, which examined RCMP CEW usage during calendar year 2008, was released on March 31, 2009. On June 24, 2010, the Commission released its analysis of the RCMP's use of the CEW during the 2009 calendar year.

There are also a few clear differences with respect to Incident Type. Specifically, youth were less likely to be involved in cases of "assault" but more apt to be involved in "weapons offences" with respect to 2010 CEW-related incidents.

2.5. Probe mode means the deployment of an activated CEW by discharging and propelling two electrical probes, equipped with small barbs that hook onto a subject's clothing or skin, allowing electrical energy to be transferred to that subject.

Active resistance is a highly varied behavioural categorization. As the term suggests, active resistance most often involves specific adversarial behaviours on the part of the subject. In 2010, active resistance on the part of subjects was identified in 123 CEW events. Over one-third (43 cases, or 35.0%) of active resistant events involved the following:

At 4:26 p.m., member no. 1 arrived with a signed warrant, and a search for the subject began. Member no. 1 was advised that the subject was hiding in the attic, underneath the insulation, as this was the only area where the insulation had been disturbed. Member no. 1 entered the residence to assist, and member no. 2 indicated that there was a knife missing from the block of knives on the kitchen counter. Given that the subject was known to be violent and may be armed with a knife, member no. 1 went up into the attic and took his CEW out of its holster with the laser light activated and advised the subject that the police knew he was there and that member no. 1 had a CEW trained on him. Member no. 1 immediately saw the subject's hands come up from underneath the insulation and he was advised to keep them raised so that police could see them, and to move slowly. The subject was very cooperative and complied with all directions asked of him. He stood up on his feet and kept his hands visible the entire time.

Passive resistance was the smallest of the behavioural categories. Unlike the classification of "cooperative", the designation of passive resistant does not lend itself to easily identifiable sub-categories. Generally speaking, passive resistance refers to circumstances where subjects were uncooperative or non-compliant, especially with regard to following police officers' instructions. For example, subjects were not listening to the RCMP members' orders, but they were not yet behaving in a way that could be perceived as being actively resistant.

1.6. Members whose CEW certification has lapsed must not use the CEW operationally until the re-certification training has been completed.

7.3.2. Training Cartridges permitted for use in training are: blue TASER simulation Air Cartridge model 44205 with a 21-foot, non-conductive nylon wire for use in RCMP scenario-based training. This training cartridge will be purchased only by CEW instructors or Division Training Coordinators.

Essentially, a conducted energy weapon (CEW) is a less-lethal device that delivers high voltage, low current, electrical shocks with the intent of temporarily incapacitating a subject through involuntary muscle contractions or pain compliance. In Canada, CEWs are prohibited weapons under the Criminal Code and as such are not available to the general public.

In other cases, negotiation and communication skills, rather than the CEW, were effective in bringing an incident to its successful conclusion.

NOTE: Candidates participating in the CEW User Course, CEW Instructors Course or the Cadet Training Program may handle/use the CEW under the supervision of an instructor as prescribed by course material.

Section 25 of the Criminal Code of Canada empowers police officers to use as much force as is necessary in enforcing the law. In situations where a police officer believes that there exists a reasonable risk of death or grievous bodily harm to any person, that section specifically authorizes him or her to use lethal force in response to the threat.

The member was advised that the subject had jumped off a snowmobile near the shed out back. The member approached the shed and advised the subject that he was under arrest and to place his hands on the wall. The subject stated that he was going into the shed, and proceeded to open the door. The member feared that there were possible weapons inside the shed, as it is a common practice for the local people to store their firearms in this manner. The member drew his/her CEW and held it at the low-ready position. The member again told the subject to place his hands on the wall. The subject appeared as if he was going to enter the shed. The member pointed the CEW at the subject's centre of mass and told him to put his hands on the wall or he would be hit with 50,000 volts of electricity. At this point, the subject complied with the commands and placed his hands on the wall of the shed. The subject was handcuffed and the CEW was holstered.

NOTE: This is a newer version of the currently approved TASER Standard Air Cartridge model 34222 which is no longer available for purchase. Model 34222 is still approved and will be phased out through attrition.

The chi-square test is a widely used method for measuring whether or not a statistically significant relationship exists between two nominal or categorical variables. In the field of statistics, a result is called "statistically significant" if it is unlikely to have occurred by chance.

On average, male and female subjects were approximately 31 years of age. In addition, 7% of all subjects were 50 years of age or older. These figures are comparable to those recorded in previous years by the RCMP.

The statistics for Deployment Type are consistent with the conclusions drawn from Table 52: i.e. the CEW is used much more as a deterrent against youth compared to the rest of the population. In particular, the figures for "Laser Sight Activated" and "Draw and Display" are both considerably higher when the subject is a youth.

While the RCMP's "V" Division, "L" Division, "K" Division, "D" Division, and "M" Division each experienced higher CEW deployment rates compared to the total Force-wide average, all divisions seem to reflect the overall trends in usage and deployment. In general, there is surprisingly little variation between divisions. In addition, there do not appear to be any "red flags" or areas of concern. For a more detailed breakdown of figures at the RCMP divisional level, please refer to tables 40 through 50 in Appendix 2.

Non-compliant behaviour, in conjunction with other situational characteristics, can also be classified as active resistance (20 cases, 16.3%). Subjects that were not cooperative in circumstances heightened by the presence of a weapon or threat cues were often noted as active resistant. The most common example of non-compliance that constituted active resistance involved subjects' unwillingness to show their hands. Illustrative examples of all three of these circumstances are provided below.

2.2. Data download means the retrieval of information, recorded and stored in the CEW about its deployment, through the data port-function by connecting the data port to a computer. A data download provides information about CEW usage which can be valuable to an investigation.

Dispatch received information from a complainant that an assault had taken place. The subject was violent, intoxicated, had a hatred/personal grudge against one of the responding members and was looking for payback. The complainant stated that if the subject knew that police were on their way, he would attempt to leave and avoid police capture at all costs. The subject was well known to police and extreme caution was always taken when dealing with the subject. The Operations Communications Centre's Risk Manager advised the three members attending to wait for backup, due to the violent nature of the subject. On arrival, the members approached the front door of the residence. The subject came to the door after several knocks and police presence was announced. The CEW was trained on the subject when the subject opened the door. The subject was told to exit the house, but he refused and began walking back inside, stating that he did nothing wrong. With CEW over-watch, two members advanced and restrained the subject's arms as he began to walk into another room. The subject then became compliant and handcuffs were placed on the subject. At this point, the CEW was re-holstered.

The RCMP's Subject Behaviour / Officer Response (SB/OR) Reporting System is a standardized method of recording subject behaviour and the use of intervention options. RCMP members are to complete a SB/OR report if they are involved in an incident where the intervention option consisted of: (a) the use of hard physical control, intermediate weapons, or lethal force; or (b) the use of soft physical control which resulted in an injury to the subject, RCMP member, or other person.

7.3.7. An operational cartridge should not be stored and carried in the extended DPM of the Taser Model X26E. Cartridges are to be stored in the cartridge carrier/holder provided on the holster.

5.6.2. Photograph the injury or afflicted area as observed, or the area of the injury or affliction as described by the subject and secure as evidence.

It should be noted that, because of the special issues that often accompany policing in Canada's northern regions, some of the Commission's previous CEW annual reports have devoted detailed attention to RCMP divisions and detachments in the North (i.e. Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut). In contrast to past years, however, there were simply too few CEW cases from the North in 2010 to attempt either generalizations or comparisons with previous years.

Figure 36 (see also Table 36) demonstrates that the decrease in CEW engagement between 2009 and 2010 is indicative of a much longer-term trend. From 2002 to 2004, the rate of deployment rose from 72.1% to 91.0%. Put another way, in 2004, almost all CEW occurrences resulted in deployment. Since that pinnacle in 2004, the rate of deployment has declined every year. By 2007, it had essentially returned to 2002 levels. The decline between 2009 and 2010 was not as precipitous as it was between 2008 and 2009, but it was still significant. It is also worth noting that the overall number of reports dropped for the fourth year in a row.

6.5.1. Review all SB/OR reports as soon as practicable after they are completed to ensure consistency with national directives.

As described in Part Six, section A.1, 65 CEW incidents (9.9%) were categorized by RCMP members as involving a cooperative subject. And, 50 (76.9%) of these incidents appear to be broadly associated with what might be termed "tactical entry" or "tactical approach". In general, these are incidents in which members were serving a warrant, or were approaching a crime in progress, and where a CEW was drawn as a precaution prior to entering a residence, other building, or situation.

7.3.1. Operational Cartridges permitted for operational use, with both the M26 and X26E are: TASER Standard Air Cartridge model 44200 with 21-foot filament.

The second issue addressed through bivariate analyses relates to the issue of injury seriousness. The RCMP's previous CEW usage reports collected information on whether subjects had been examined at a medical facility. Medical examination was taken as a rough proxy for seriousness or severity of injuries, with the caveat that subjects were sometimes taken for medical exams even if their injuries were not directly related to the use of a CEW.Footnote 18 However, as noted earlier in Part Three, the present SB/OR Reporting System generates far less detail regarding the consideration of injuries. As shown in Table 6 (Appendix 2), while the SB/OR Reporting System collects data and information related to subject injuries, very few cases of injuries were reported. Medical treatment was offered in a large proportion of cases involving injury, and such offers were almost always accepted by subjects. The new Medical Examination variable is derived from the SB/OR variable Subject Level of Treatment, which is filtered to ensure that only injuries related to the use of the CEW are considered.

Similar to push-stun mode, probes were usually deployed only once (Figure 17a; see also Table 5 in Appendix 2). Further, when deployed in probe mode, it was not uncommon for the CEW to be cycled only once (Figure 17b); cycles of greater number occurred in only 9% of successful probe deployments. A value of 0 for Number of Cycles indicated that one or both probes did not make contact with the subject and, as a result, the weapon did not cycle (see also Number of Probe Impacts in Table 5, Appendix 2).Footnote 16 The chest, back and lower body were the most common impact locations. And, in contrast to push-stun mode usage, RCMP members were more apt (60%) to employ the probe mode for a full cycle duration.

The member attended the subject's residence to arrest him for breaching his probation order. The member was invited in by the subject's mother and step‑father. The member then spoke to the subject in the entryway and informed him that he was under arrest for breach and would be spending the night in custody. The subject appeared to understand. He started to cry and went over to hug his mother. After the hug, the subject then proceeded to walk into the kitchen, so the member detained the subject by grabbing his arm and again informing him that he was under arrest. The subject pulled away from the member and said: "Don"t touch me." It was at this point that the subject reached for a knife on the kitchen counter, turned away from the member, stabbed his own stomach, and fell to the floor. The weapon was a butter knife and was thrown off to the side by the subject. The kitchen was very small; the subject's mother was on his right side and his girlfriend was on his left, while his father was also in the kitchen. Due to the small size of the room and the number of people present, the member got on the subject's back, unholstered his CEW and turned it on. The CEW was placed in the back of the subject and the member demanded that the subject put his hands behind his back. The subject refused and grabbed a hold of the kitchen table. The member gave the subject the CEW warning and told him again to put his hands behind his back. The subject then put his hands around his back and was handcuffed.

In contrast to assaultive cases where subjects fight with police officers, there was a small number of cases (28, or 14.6%) where the subjects' clear intent was to do serious harm to the RCMP members.

While RCMP members were setting up a perimeter, the subject exited the house unexpectedly. A member told the subject to be still, but the subject hesitated for a moment. Observing that the subject was tempted to flee, the member deployed a CEW to prevent the subject from either entering a vehicle and leaving the scene (and possibly attempting to realize his plan to kill his ex-wife's family), or possibly using the weapon that he had in his possession to harm the officers.

The Commission would also like to thank Mr. Simon Baldwin of the RCMP's National Use of Force Unit for his cooperation and assistance in terms of responding to requests for data and information in a timely and comprehensive manner.

Simply stated, with one notable exception, none of the variables analyzed were significantly related to medical attention. Figure 24 (see also Table 15 in Appendix 2) shows an association between Deployment Mode and the need for medical attention. Specifically, probe mode produced a greater proportion of medical cases than did push-stun mode.

6.4.3. If required by provincial or territorial policy, forward quarterly and annual reports on CEW use to the appropriate provincial or territorial ministry.

Having established a descriptive framework in the previous section, this report now turns to bivariate relationships. In contrast to descriptive statistics, bivariate analyses allow for the testing of relationships between two variables. For example, the first set of analyses presented in this part of the report considers the relationships between CEW deployment and the various conditions surrounding the events. Specifically, chi-square (x²)Footnote 17 analyses were conducted to compare CEW deployment (or non-deployment) with the following variables:

The situation with regard to CEW usage in mental health incidents declined in 2010 by about two-thirds the number reported in 2009. Figures 50a and 50b (see also Table 59 in Appendix 2) indicate that the proportion of both total CEW reports related to mental health incidents and total CEW deployment or engagement reports involving the mental health designation returned to 2008 levels after increases in 2009. As well, the percentage of mental health reports where the CEW was engaged continued to fall, showing a trend of declining deployment rates since 2005.

The probability of deployment of the CEW for these types of events was also greater than the overall average, particularly when engaging the device in probe mode (Figure 56a and Table 63 in Appendix 2). In other words, the CEW is more likely to be deployed in CEW incidents when the subject is deemed to be suffering from a mental health issue (Figure 56b).

Incident Type (Figure 20 and Table 10), Subject's Age (Figure 22 and Table 12), Emotionally Disturbed (Figure 23 and Table 13), RCMP Division (Figure 21a and Table 14a) and Member's Years of Service (Figure 21b and Table 14b) all showed a similar pattern of a positive relationship.

It is somewhat surprising that the numbers pertaining to perceived substance use and alcohol were relatively low for youth compared to the total population (see Table 55 in Appendix 2).

A summary of the factors relevant to the circumstances surrounding CEW usage by the RCMP in 2010 is presented in figures 1 through 4 below, and in Table 1 (see Appendix 2).

Zero (0) probe impact indicates that neither probe made contact with the target. One (1) probe impact indicates that one probe made contact with the target, while the other probe did not. Two (2)probe impacts indicate that both probes made contact with the target. The CEW will only cycle if both probes make contact with the target.

7.2.2.3. Use only the following authorized AA batteries listed in order of preference: Taser International (Rechargeable NiMH 44700); and Eveready Energizer ACCU (Rechargeable NiMH in 2100 mA or more).

9.1.1.3. a supervisor of an incident, a Divisional Use of Force Coordinator, a Criminal Operations Officer, or NCROPS determines that testing is warranted in the circumstances, including in order to address any concerns about the performance of a CEW or the circumstances or impacts of its use; or

The remaining 53 assaultive events (22.1%) were more ambiguous and difficult to further classify. Often, it was simply the totality of the situation which led to the assaultive assessment, as in the following example:

As in previous years, RCMP members perceived substance use amongst subjects in a large percentage (76.0%) of events involving the CEW. Alcohol was believed to be involved in two-thirds of all cases, while drug use was suspected in over one-quarter of incidents. While these figures are high, it is worth noting that they have been in decline over the past four years. These declines are not precipitous, but it remains unclear as to why substance use is playing a slightly diminished role in CEW incidents.

As per the RCMP's CEW policy, "Members must fully and accurately report and articulate their actions." In the present study, however, it was observed in numerous cases that the various narrative sections of the SB/OR Reporting System filled out by RCMP members were incoherent, inaccurate and/or incomplete. As a result, the RCMP should consider reviewing its policies and practices regarding quality assurance and the inputting of data and information about CEW use and deployment into the SB/OR Reporting System. Moreover, the RCMP should consider whether it is necessary to provide additional training or guidance to members and those in supervisory roles about this issue.

Regular Member (Police Officers) – For the purpose of the present report, the term "member" refers to regular RCMP officers who are trained and sworn as peace officers. Civilian members and public service employees of the RCMP are not authorized to use CEWs.

CEW Challenge – Standard form of police articulation, prior to the use of the CEW, designed to identify the officer and make the subject aware of the consequences of CEW deployment (Example: "Police – stop – or you will be hit with 50,000 volts of electricity!").

5.6.4. Collect the expended cartridge and probes as taught in CEW training, and secure them as an exhibit for a minimum of 90 days. Cartridges that are not required for criminal, civil, or code of conduct investigations can be disposed of after 90 days.

The presence of a weapon was identified in over 60% of CEW events in 2010, marking a significant increase over previous years (Figure 13a; see also Table 4 in Appendix 2). This is an area that experienced a shift in languageFootnote 15 in the RCMP's SB/OR Reporting System, possibly producing the change in the results. Nevertheless, this should not downplay the significance of the rise in the presence of weapons; it merely suggests that some proportion of the increase might be attributable to differences in the manner in which the information is currently being recorded by the RCMP compared to previous years.

9.1.5. A CEW that tests outside of the manufacturer's specifications will be removed from service by the Division and will be returned to the armourer for destruction.

Moreover, as noted previously in Part Seven of the present report, mental health incidents in 2010 primarily involved subjects who were suicidal (67.4%), most of whom were in possession of a weapon such as a knife (figures 54a and 54b; see also Table 63 in Appendix 2).

In the Commission's previous CEW annual reports, the present section has been titled Narrative Summaries, whereby qualitative coding techniques were used to provide more detailed information on the context that gave rise to CEW incidents and to produce broad categories of CEW-related behavioural circumstances. However, the RCMP's SB/OR Reporting System now includes a classification for Subject Behaviour (see Table 4, Appendix 2). As a result, Part A of this section instead tries to provide the context for these classifications. Part B, on the other hand, looks more directly at the issues of escalation and de-escalation in relation to CEW usage.

SB/OR Example: The Subject showed active resistant behaviour by running away from members through the hallway, turning left into the last bedroom.

SB/OR Example: RCMP members ordered the subject to show his hands. He did not comply and attempted to stand up, displaying actively resistant behaviour.

There are two groups of subjects that require special consideration in the context of CEW usage and deployment by RCMP members. The first are youths, defined here as subjects under the age of 18, while the second are subjects identified in CEW reports as exhibiting mental health problems or suicidal behaviour. This section of the report uses descriptive statistics to better understand the nature of CEW cases involving these two groups. The various figures in this section (and the corresponding tables in Appendix 2) are comparable to the descriptive statistics found in Part Three of the present report.

7.2.2.1. Given the specialized and particular power supply requirements for the M26, only RCMP-approved batteries are to be used. See App. 17-7-2 for battery-reconditioning method.

As member no. 1 attempted to open the door of the subject's vehicle, finding it to be locked, the subject threw his vehicle into drive and, revving the vehicle to high RPMs in the process, indicated his intent to drive away from the members, thus exhibiting active resistant behaviour. An arm bar technique was applied to the subject by member no. 1 as an initial attempt to have him comply with the ongoing demands to stop his actions. The subject's vehicle then suddenly became mobile as member no. 1 had a firm hold on the subject's left arm, thus pulling the member forward beside the moving vehicle. Member no. 2 observed this and felt that the subject may be holding onto member no. 1 or that member no. 1 had become entangled with the vehicle or subject in some way. Member no. 2 interpreted this as being an imminent threat to the safety and well-being of member no. 1, displaying behaviour concurrent with grievous bodily harm or death. Member no. 2 deployed OC spray in an effort to stop the threat of these actions. Member no. 2 deployed a burst of the pepper spray into the facial area of the subject just as he was beginning to accelerate down the road with member no. 1 in tow for approximately 25 feet. Members then observed the subject continue to accelerate down the road, his driving pattern continuing to deteriorate until the subject ultimately entered a ditch approximately 200 metres down the road and coming to a full stop in an open field. Given the events that had just transpired and the fact that the subject had clearly shown no regard for the safety of members, member no. 1 approached the vehicle and drew the CEW as to have an additional intervention option available should the subject continue demonstrating reckless behaviour. The subject acknowledged that he would now comply with police commands and was arrested without further incident.

Since 4th quarter data and, by extension, 2010 annual data broken down by RCMP division were not available from the RCMP at the time of writing this report, 3rd quarter data from 2010 pertaining to RCMP members who were CEW-certified was used as a proxy measure.

6.1.7. As outlined in ch. 17.8., complete a Subject Behaviour/Officer Response (SB/OR) report every time a CEW is used, and attach the completed copy to the operational file. For the definition of ‘use' of a CEW, see sec. 2.8.

7.1.1. The CEW is a prohibited firearm. The CEW and its cartridges must be secured in accordance with the Public Agents Firearms Regulations.

2.6. Push stun mode means pressing or pushing an activated CEW onto designated push/stun locations on a subject, allowing electrical energy to be transferred to that subject.

With respect to tables 57 and 58 in Appendix 2, the very small number of cases renders any comparisons virtually meaningless.

7.4.2.2. after the download is complete, ensure the CEW is returned to the Senior Armourer, "Depot" Division for repair or replacement. See FM ch. 6.4.

As per the RCMP's CEW policy, "Where tactically feasible, members will issue a verbal warning so the subject is aware that a CEW is about to be deployed." The RCMP should ensure that the data and information associated with the issuance of verbal warnings during CEW events are adequately captured as a mandatory field in the SB/OR Reporting System.

Several important subject characteristics are captured in Table 3 (see Appendix 2) and displayed in figures 7 through 10 below. The overwhelming majority (91.4%) of subjects involved in 2010 CEW-related incidents were male.

6.3.2. Ensure the original CEW package received contains one CEW, fully charged Digital Power Magazine (DPM), one instruction book, one DVD, and one holster (Blade Tech Tek-Lok - for plain clothes use only).

The subject had his hands in his pockets and RCMP member no. 2 requested that he remove them. The subject then turned to member no. 2 and said, "What are you going to do if I come at you?" While stating this, the subject clenched his right hand into a fist and motioned in an aggressive manner toward member no. 2 (who was standing on the subject's left side). Member no. 1 and member no. 2 therefore took hold of the subject on each side and put him onto the floor. Member no. 1 went to the ground with the subject, who, during this time, was still assaultive and kicked the member with both feet. Member no. 1 fell backward and hit the wall. Member no. 1 stood up and drew the CEW, as the subject was still assaultive toward member no. 2, who was trying to gain control of the subject's arms. The subject had spit in member no. 2's face and continued in an assaultive manner. The CEW was turned on by member no. 1, and the cartridge was removed. Member no. 1 leaned down and used the CEW in push‑stun mode against the subject's lower back. There was no warning given for the CEW at this time, as the members were physically attempting to gain control of the subject. Member no. 1 used the CEW in push-stun mode due to the close proximity of the subject [emphasis added]. Member no. 2 was trying to take control of the subject's right hand while Security personnel tried to assist by taking control of the subject's left hand. After one cycle of the CEW, the subject was told to give the police his hands. Member no. 1 then gave Security personnel handcuffs while member no. 1 remained kneeled down with the CEW on the subject's lower back in case it was needed. Member no. 2 assisted with handcuffing the subject.

Introduced in a number of pilot jurisdictions in 2009, SB/OR reporting fully replaced the RCMP's CEW usage reports in 2010. As a result, the present report is based solely on CEW data collected through the new SB/OR Reporting System. This change in reporting mechanisms is reflected in a number of areas throughout the report.

In the following example, the subject was looking for a means of escape, but had not yet attempted to effect his escape.

The subject was off his medication. He was believed to be in possession of a knife. The subject was in his room. The member walked to the doorway and asked the subject to exit the room, informing him that he was under arrest under the Mental Health Act. The subject refused to leave and stated, "F**k you," clenched his fists, and took a bladed stance. The member drew his CEW, prompting the subject to back off and drop his fists so that his hands were visible. The members controlled the subject with soft physical control and placed him in handcuffs. The subject was then transported to the detachment for further processing.

The RCMP should continue to make refinements to its SB/OR Reporting System. For example, as was done in its previous CEW reporting system, the category of "drugs" should be further broken down into sub-categories, such as marijuana, cocaine, heroin. In cases where this information is known, it could prove valuable in terms of monitoring trends around CEW usage and deployment.

6.2.1. Ensure members submit a SB/OR report. When a CEW was used, review reports for adherence to applicable policies as soon as practicable.

Taser® – Brand name for the conducted energy weapon used by the RCMP. There are also other companies that manufacture similar devices.

According to Figure 44 (see also Table 54 in Appendix 2), in 2010, youth-related CEW incidents drew slightly fewer RCMP members relative to the overall average.

OnlineTasertraining for security guards

The statistics on deployment continue to demonstrate a downward trend as noted in the Commission's previous annual CEW reports. CEWs were deployed in one (1) out of three (3) incidents in 2010, showing a slight decline compared to 2009. The threatened use of CEWs by RCMP members is being used more and more as a deterrent or method of de-escalation, without the device having to be deployed.

1.2. The fluorescent yellow stickers on the CEW are intended to differentiate it from the pistol and must not be removed or altered under any circumstance.

In recent years, the use of the CEW by the RCMP has been examined in a number of Chair-initiated complaints. Resulting reportsFootnote 6 made a combined total of 45 recommendations to the RCMP, including 8 specifically related to the CEW.

*There were a small number of cases where the number of cycling was recorded as 0 (67, 3.0% of total) or missing (17, 0.8%). As a result, "Cycling" columns may not add up to 100%.

As the name suggests, this category, identified in 192 CEW events, represents the most dangerous level of subject behaviour.Footnote 20 In these incidents, a subject demonstrates either the intent to cause serious harm or the capacity to do the same, or both. In 2010, the most prevalent type of incidents within this category (82 cases, or 42.7%) involved subjects deemed to be suicidal. These subjects were almost always in possession (or had just been in possession) of a weapon. The following is a very typical police encounter with a suicidal subject. Notice that it was not just the RCMP members' safety that was at issue. In these cases, members were equally as concerned for the subject, along with other parties that may have been involved.

3.1.3. Where tactically feasible, members will use de-escalation techniques and/or other crisis intervention techniques before using a CEW.

Members already on shift had located a suicidal male who had left the hospital and had stated that he was going to have the police kill him. They called for a CEW, as no members on scene had one. A member departed for the incident from the detachment, carrying a CEW. When the member arrived on scene, he took cover behind the police vehicle beside the subject. Five members had their firearms drawn and one officer was verbally engaging the male, who was holding a knife up to his throat. After approximately 30 minutes, the subject threw his knife down and complied with police direction to kneel down, then lay on his stomach to be handcuffed.

Axon MasterInstructorSchool 2024

6.3.4. Keep an adequate supply of CEWs, RCMP-approved holsters, CEW operational cartridges and replacement batteries/DPMs on hand.

One of the factors that have been added to the SB/OR Reporting System concerns an assessment of the subject's mental health in CEW incidents. The proportion of subjects judged to be emotionally disturbed was just over half (Figure 10; Table 3 in Appendix 2). The phrase "emotionally disturbed" is extremely broad and lends itself to a wide margin of subjectivity and interpretation. The rate of subjects who were perceived as Emotionally Disturbed by RCMP members, which is approximately three times as high as the Mental Health incident type designation, suggests that members routinely encountered disturbed individuals in events that were not categorized as Mental Health events. Disturbance is evident in a preponderance of incidents involving kidnapping, weapons, and threats; and, it is often cited in cases involving disturbing the peace, obstruction, and assault. The widespread prevalence of disturbance points to the importance of understanding the intersection of CEW usage and mental health. Further discussion on this topic is provided in Part Seven of the present report.

Probe Mode – Deploying an activated CEW by discharging two electrical probes, equipped with small barbs that hook onto a subject's clothing or skin, allowing electrical energy to be transferred to that individual.

6.4.2. Follow divisional internal processes and reporting requirements to ensure that any matter associated to CEW usage is resolved, including referral to division Professional Standards when appropriate, if an issue is identified during the review.

AxonTASER10

7.4.1. In compliance with the Canada Labour Code, faulty or malfunctioning CEWs must be marked or tagged accordingly and be removed from service.

Figures 29a and 29b (see also Table 31 in Appendix 2) reveal several key changes pertinent to CEW deployment. The percentage of incidents involving the Perceived Possession of a Weapon rose in 2010. The wording of this variable in the RCMP's SB/OR Reporting System is subtly different than in the previous year; specifically, the word "perceived" was added. While this same variation had no discernible impact on the Substance Use variable presented in Table 30, it is possible that identifying substance impairment always has a strong subjective element and that adding perception to reporting is unlikely to alter that assessment. Conversely, it is possible that the addition of "perceived" to weapons possession broadened the scope of weapons involvement. Again, this suggestion is not meant to downplay the importance of these findings. Rather, the nearly 12% increase in the percentage of events involving an edged weapon and the 3% increase in cases involving firearms suggests that a degree of caution in the interpretation of the results is warranted.

Several members were called to a mental health and drug addiction treatment centre. While en route, dispatch relayed that workers and the local fire department were indicating that a male was out of control and being extremely violent. The male subject was said to have HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C. In addition, he was known to bite and spit at people. The subject was said to be running around unchecked within the facility. Lastly, the subject was said to be under the influence of methamphetamine and heroin. When police arrived, the subject had isolated himself in a shower room. He was ranting, screaming, swearing, grunting, and threatening to hurt anyone who came through the door. Given the members' extensive experience in matters such as these, the members felt that a confrontation with this individual was likely imminent. The subject was displaying "assaultive" behaviour before police even entered the room. A member feared for the safety of on‑scene officers and of the treatment centre staff. Members also feared that the subject may harm himself if left in this state for too long. Attempts to negotiate with this male by staff had failed and he was not responsive to verbal communication. No further negotiation with the subject was attempted, as it was felt that he may further barricade the door and prepare for any police entry into the room. An arrest team of five members was formed, and member no. 1 carried the CEW and would be the first to enter the room. Member no. 2 pushed open the door and member no. 1 made entry into the room. The member announced that he was a police officer and that the subject should get onto the ground. This demand was made twice. The suspect yelled back "F**k You" and began to rise to his feet. The member took this action as a threat cue, and feared that both he and the other members were about to be attacked by the subject. This caused the member to fear for the safety of all parties on-scene. To defend himself and fellow officers, the member deployed the CEW in probe mode. It was not practicable for the probes to strike anywhere else other than the subject's torso. The deployment was deemed successful and the subject tipped over sideways into the bathtub. He struck his head on the edge of the tub falling roughly 8–12 inches. He suffered a small cut to his ear. The member allowed the CEW to cycle until members were able to come and remove the subject from the tub. Once on the ground, the subject attempted to continue his assaultive behaviour during handcuffing, and a short two-second burst of the CEW was utilized to get the subject handcuffed. A spit hood was applied over his face to prevent him from spitting into members' faces, eyes or mouths. Obviously, the subject's medical condition was of grave concern to everyone involved. The subject continued to thrash once placed on a bed and, as such, member no. 1 used the cord-cuff restraining device to halt the suspect's aggressive actions. The subject was taken to hospital for further assessment with regard to his mental state, his state of intoxication, the small cut to his ear, and any medical issues which might arise from the drugs, the exertion and the CEW deployment.

For example, in contrast to the overall figures, Figure 43 (see also Table 53 in Appendix 2) suggests that CEW reports involving youth were proportionately much less likely in British Columbia - "E" Division (11.4% for youth vs. 26.8% overall) and Alberta – "K" Division (11.4% for youth vs. 20.6% overall) and much more prevalent in Saskatchewan – "F" Division (31.8% for youth vs. 20.6% overall), Nova Scotia – "H" Division (15.9% for youth vs. 5.9% overall) and the Yukon – "M" Division (6.8% for youth vs. 1.8% overall).

Baldwin, Simon and Kim Lackie. RCMP Quarterly Report on Conducted Energy Weapons, July 1, 2010 to September 30, 2010. Ottawa: National Use of Force Unit, Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

In 164 of the remaining 165 cases, the CEW was deemed to have been ineffective in de‑escalating the situation; 56 of these cases (15.9%) were considered "tactical" in nature.

The subject became actively resistant again by pulling away from hospital staff. The member attempted to intervene to assist with the subject, but the subject quickly became assaultive towards the member by clenching his fists and stating that he was going to beat up the member. The subject began to approach the member with his fists still clenched. As a result of the subject's emotional state, the member feared bodily harm and unholstered the CEW. The subject stated to the member that he would not be "tased" and insisted that he was still going to beat up the member. The subject then turned and walked away from the member. The member did not deploy the CEW, but did point it at the subject and issued the CEW challenge. The subject then changed direction and started to walk toward the hospital where he was met by his mother. The subject was subsequently admitted by his mother to a psychiatric hospital overnight for further observation and assessment.

2.4. Operational cartridge means an RCMP-approved cartridge for operational use and training, except scenario-based training.

Moreover, the average number of CEW usage reports per RCMP member was 1.24 in 2010, which represented a very slight decrease compared to the previous year's average of 1.26 (Figure 6; Table 29 in Appendix 2).

7.1.2. CEWs must be carried in an RCMP-approved holster (see App. 17-7-1) on the member's non-dominant side, e.g., opposite the sidearm.

Registration: Cost of the course is $375 per student. All registrations for this course close 7 days in advance. Students wanting to access the system must first have an account and login or create a new account at MyAxon. There is a 24 to 48 hour verification approval process. Help with enrolling and payment options can be found here: Help