Environmentally-friendly and Smokeless Incinerator - incenirator

Additionally, I wanted offline-video capabilities, and only Plex and Oculus Video support those on Go (in spite of the standard Netflix Android and iOS apps offering offline-download viewing).

The bigger compromise on the screen's part, really, is a narrower field of view (FOV) than Oculus Rift and HTC Vive. Those headsets offer 110 degrees of FOV by default, while Oculus Go matches its Gear VR sibling at roughly 101 degrees.

Ars Technica has been separating the signal from the noise for over 25 years. With our unique combination of technical savvy and wide-ranging interest in the technological arts and sciences, Ars is the trusted source in a sea of information. After all, you don’t need to know everything, only what’s important.

Oculus may not much care for this weird description, but its new Go headset is the Genica MPTrip of its time. Here is a comfortable, solid-performance headset, with a better pixel resolution than the pricier, PC-specific Rift, that can deliver an acceptable-compromise dive into the VR difference. No more coordinating phones with plastic VR shells or slapping phones into cardboard cutouts or zapping your phone battery to try out unoptimized "VR" content. The Go is not perfect, but for many people, we recommend spending $199 right now to have a good, wire-free time in the bustling-yet-fractured Go ecosystem.

Should you wish to guide an on-screen avatar or hero, for example, you can't expect to hold the touchpad in a certain direction as if it were a joystick. Oculus Go developers must come up with other solutions, and mini-game compilation They Suspect Nothing takes a few stabs at the problem. All of them suck.

I wanted a media player that would let me have it all. First on my list: the ability to transform my virtual cinema display however I saw fit. Down on the ground? Up in the sky? Closer to or farther from my face? Plex and Netflix could both do this, with Plex's virtual screen being the easiest to move around as I saw fit. Netflix's similar free-transform options were hidden in a far corner of its "virtual home" interface, while the built-in Oculus Video app only let me move its virtual screen, not resize it.

Yet Oculus Go's LCD panel doesn't look cheap. For one, its 2560x1440 resolution exceeds its pricier home-VR siblings (2160x1200) by a scale of 42 percent. That boosted resolution, combined with "fast-switching" LCD technology, make it look considerably better than other LCD-driven VR headsets.

The biggest catch with my long-session Go use comes from its budget-minded battery. We eventually learned that Go comes packed with a 2,600mAh battery—just shy of many 2016 flagship phones that use the same Snapdragon SoC. Testing exactly how well that battery works in this headset, however, has been difficult.

Recently, the path to "cheap," accessible VR required nothing short of a pricey smartphone. Whether you buy into Samsung's Gear VR ecosystem or Google options like Daydream and Cardboard, you're expected to slap a phone into a headset, like bread into a toaster. An add-on headset's lenses then translate whatever stereo image appears on your phone screen, and if you paid for something more elaborate than Cardboard, you can also expect a simple hand controller and additional motion-sensing capabilities. Otherwise, you commonly control apps and games with nothing more than the direction of your visual "gaze."

What's more, Go is just smooth, comfortable, and powerful enough to rev up my "VR might happen" fever and optimism all over again. I am already imagining more ways in which a wireless virtual display, mixed with hand-tracked controls, would improve my day-to-day life. I am already selling my friends on this future by handing them an affordable headset and watching them ask when they can buy one.

Why am I bringing this up in an Oculus article? Because while putting the Go—a standalone, no-wires, no-phone-needed VR headset—through its paces, I couldn't help but rewind time to a serviceable, lacking, and affordable glimpse at the future of how I'd interact with technology.

Upside downtriangle road signmeaning

The headset's other intangibles raise this use case above "party trick." The screen's pixel density is good enough for comfortable, clear video content. The combination of Go's cloth-strap fit and foam face cushion aren't quite as elegant as the Rift, which uses a firmer plastic strap, so it feels a little more forward-heavy. But it's still fine for long sessions—and certainly more comfortable and weight-balanced than the original Vive. And by building the Go's LCD display, which has the same size (5.5-inches) as other Gear VR panels, directly into the headset, Oculus and Xiaomi have engineered methods to evenly dissipate heat across the Go's flat front.

What's more, Oculus sent us a working headset last week for the sake of a review—and I have no shortage of thoughts about what Oculus has gotten right with its first "budget" VR product. Before I break down performance, software, features, and limitations, I want to set the scene by rewinding to another era in which a "futuristic" gadget sector began plummeting in price.

The other major "corner-cutting" feature in the Go is its LCD screen. VR purists are familiar with OLED technology, since its benefits—deeper, truer blacks, less ghosting than existing LCD panels—made it the de facto choice for early VR headsets. But OLED costs much more to implement, both because of its raw materials and because the panels are harder to perfectly calibrate.

Circleroadsigns

Additionally, the above charts for system performance shouldn't be taken as Go gospel. Games and apps can elect to toggle Go's optional overclock (which, among other things, enables that high-end 72Hz screen refresh; the screen otherwise defaults to a 60Hz frame rate). As a result, various games and apps push Go's SoC (and sip the battery) at dramatically different rates. Android's stock Web browser, Chrome, runs a lot more efficiently than fully 3D games, for example, but there's also the simple fact that switching apps and bringing up various menus brings up much more 3D data and rendering than most Android SoCs are built for.

Surprise! Oculus released a new virtual reality headset today. The Oculus Go standalone headset is now for sale at Amazon, Newegg, and Best Buy starting at $199—yes, $199, with no other hardware required—following a retail-launch unveil at Facebook's annual F8 conference.

Really, the Oculus Go controller doesn't give Anshar players much in the way of control possibilities. It includes only one action button (the trigger) and one unwieldy touchpad. The reason for that might be to maintain compatibility with Samsung Gear VR, which shipped in 2014 with a default, nickel-sized thumbpad on the headset's side. Unlike the trackpad found on the HTC Vive wand, which can pick out precise taps and directions, Gear VR and Go limit users to basic swipes in four cardinal directions. That's likely because it's hard to tap or swipe precisely on Gear VR's itty-bitty pad, but Oculus had an opportunity to expand on this functionality with the Go ecosystem going forward.

That doesn't mean the combination of VR presence and simple, imprecise pointing can't unite for solid games. Oculus Go launches with the recommended likes of République, a PC and touchscreen stealth-puzzle game whose new VR version leans nimbly into Oculus Go's limits; Wands, a simple-but-effective magic-dueling PVP game; and Catan VR, a board game that would benefit from pure hand-tracking but still sells a solid wood-for-sheep experience.

What does a yellowtriangle road signmean

For the fast-switching uninitiated, here's a quick (and admittedly meager) primer. LCD panels' lights can activate individually at an incredibly rapid rate, but when they need to be completely dimmed, that "instant" process can take hundreds of times longer, and the result looks like a "ghosting" shimmer. (For a reminder of how bad this can look, watch high-speed content like sports on an old LCD TV—then multiply that by the VR issue of a screen resting centimeters from your eyeballs.) Different solutions have since been proposed to slash the time needed for individual pixels' total dimming; in one, electric fields are rapidly applied to an LCD panel's molecules in more inventive ways. While Oculus hasn't been forthcoming with its own take on the concept, its implementation is absolutely impressive.

Also, much like phone-driven VR headsets, Oculus Go only recognizes three degrees of freedom (3DOF). This means you can expect realistic VR effects when you rotate or tilt your head. As soon as you lean in any direction, however, the effect is broken. Go does not offer positional tracking while seated, and it certainly doesn't work if you get up and walk. The Samsung Gear VR operates with the same limitation, and as a result, Oculus Go's app selection is pretty much identical to that of Gear VR's.

VR is an isolating experience, but at least TV- and monitor-connected systems include screen-share features by default—and some games do really clever things to make their second-screen content all the more enjoyable for friends in the room. I'm still a huge fan of makeshift VR Pictionary, but such an experience is impossible on Oculus Go.

More pixels, combined with faster switching, result in an LCD panel that's apparently quite cheap to manufacture while looking more like its pricier OLED equivalent. To be fair, fast switching doesn't fix the other primary issue with LCD panels—that individual pixels are never truly black, due to light bleed—and Oculus Go doesn't apply any Samsung-like "quantum dot" solution to the matter. (Meaning, we're not noticing light-frequency tricks to reach near-black levels.) You won't stick your face into Oculus Go and think the company sliced a beautifully calibrated Macbook Pro display behind these lenses. Color accuracy is decent, but there's a slight washed-out look to an average, brightly lit scene.

I might not pay $200 for a VR gaming system with the limits or fragmented library listed above, and I might not pay $200 just to comfortably generate a virtual movie screen above my bed. But all of the little ways I've dabbled with Go, including the admittedly fun act of surprising friends with its quality and features, keep me coming back and thus hovering at the "this is worth $200" mark.

Thus, my optimism about Oculus Go lands in a different use case: as a legitimate way to consume simple, minimally interactive content in comfortable fashion.

Blanktriangle road sign

One of TSN's mini-games asks players to rotate the Go controller, which makes a character move left and right along the outside of a ring. The Go controller's recognized rotation range is a little wonky, so to comfortably pull this off, I had to hold the controller with both hands. In another mini-game, players must aim a laser at a playfield, allowing you to move around a little robot avatar who follows your laser. This is frustratingly imprecise, especially because the Go pointer only offers relative motion tracking, not absolute. You can rotate and twist it, but moving the thing side to side or forward and back won't register.

In TSN, craning and positioning my hand to aim exactly where I wanted my robot hero to run never made 100-percent sense, and the urgency of the game's challenge didn't help matters. Racket Fury Table Tennis is a million times worse, because the Go controller simply cannot translate that sport's accurate arm and wrist motions. The game instead auto-warps players so that their striking angle always lines up with the ball's motion, but lining up a shot is still impossible. In spite of its visual polish and steady frame rate, this control issue alone makes Racket Fury as bad as an Atari Jaguar launch game.

You can connect Facebook credentials to share your Go's live feed of gameplay or app use over the Internet. But if you simply want to let someone else nearby see what you're seeing, there's currently no wired or wireless way to broadcast your VR images to a local screen. As a result, I get the feeling that Oculus Go's primary testers live alone. Every time a friend strapped into my test unit, our social interaction was immediately hobbled. While a friend was telling me about pleasant surprises within Oculus Go, I'd pull out my smartphone or tidy up my apartment while asking occasional questions (though Go's default speakers do a good job letting in nearby conversations, at least).

Redtriangle road signwith exclamation mark

Just be warned: the volume is still noticeable enough for anyone else nearby—imagine a standard speakerphone call at roughly 33-percent volume—and anyone who wants to hide their Oculus Go audio will appreciate its headphone jack. (You'll also want headphones for higher-volume playback; Go's built-in speakers only get so loud.)

That's the rub with any Oculus device: Facebook holds the keys to your data even if you elect not to attach Facebook credentials to an Oculus account. In spite of policies changing to comply with recent European regulations, you should take a long look at what Facebook—and various critics—say about the data it collects.

Admittedly, there's no mistaking the increased fidelity when returning to a 90Hz VR headset, but everything about Oculus Go's panel, including its fast-switching capabilities and higher resolution, adds up to better-than-good-enough. I can zip around in Anshar for long sessions without feeling like the screen or performance are playing tricks on my tummy, and the same goes for high-speed launch games like light-gun shooter Coaster Combat and skydiving curio Rush. (I say this as Ars' resident "bad VR makes me sick" staffer, and I've long criticized apps that aren't optimized for VR comfort.) Additionally, Go games and apps can employ "foveated rendering," which reduces the resolution of an image's edges for the sake of increased performance. I tried to notice this trick during my Go testing, but I couldn't pick it out.

This player was bulky and ugly with awful buttons and iffy skip protection (remember skip protection?), but for a few years, I loved it. I remember riding the bus or driving between distant cities and listening to complete album after complete album, with no CD switching or song repetition, and feeling like the future was now. Or, at least, the future that I could afford was now.

With this combination of apps, I can lie in bed, turn the brightness down on my Go display, and watch movies or TV on a screen that virtually hovers in a fixed position above my head. And, seriously, don't knock it until you've tried it. I've done this every night since getting the Go. Instead of propping my head up and fixing it to angle at a television or setting a laptop screen on some pillows, I can fidget in bed and have a clear video-viewing angle however I lie.

The game's polygon and effects budget look like the stuff of a finely tweaked PlayStation 2 game, and its action stands out thanks to a locked frame rate of... 72Hz. VR experts may look at that number and scoff, as reps from both Oculus and SteamVR have long insisted that 90Hz is the frame-rate sweet spot for VR panels. But Oculus representatives insist that a slightly lower refresh rate will suffice for clear, comfortable VR action, and I am here to say that a full week of Go testing has proven this out.

Redtriangle road signmeaning

But neither an Alf doll nor putting sticky tape on the proximity sensor worked for our tests. Go seems to require a combination of a sensed face and head or hand motion to remain on; without these, it automatically shuts down after roughly five minutes, and the device's settings and menus don't let you adjust this in any way.

Go's setup screens insist this is required "to discover and set up nearby headsets, and more." But the only thing that happens in this step of the setup phase is that your smartphone looks for a Go headset in your general GPS vicinity, then copies that headset's serial number. At that point, the app asks for Bluetooth access to transfer data from your phone (particularly Wi-Fi credentials) to your headset.

Crack the Go open and you'll find a motherboard loaded with typical smartphone parts, particularly the Qualcomm Snapdragon 821 system-on-chip (SoC). You may remember that Snapdragon model number from late 2016, when it debuted in flagship phones like the first Google Pixel (and was itself nothing more than a marginal, clock-bump update for the Snapdragon 820). The rest of the spec package resembles Android's late-2016 era, as well, with 3GB of RAM, 32GB of onboard memory, and performance numbers that fall just shy of 2016's Google Pixel. (If you're keeping score, Chinese phone manufacturer Xiaomi is largely responsible for Go's hardware, and the loud "MI" logo on its side serves as a reminder.)

Which makes the Oculus app's final demand all the more glaring: you can't boot Oculus Go without letting the Oculus app access your smartphone's GPS signal.

Triangular signs mean

In good news, Oculus Go doesn't have any cameras. That means you don't have to necessarily worry about the company tracking and logging biometric data like your height or using camera images to estimate what your home looks like. The Go also mostly functions without any Facebook-account attachment. The exception is access to one-click sharing of photos and videos of your games and apps; instead, you'll have to plug your headset into a computer, using a micro-USB cable, to grab those files.

The catch in Anshar's case is that you can't use your gamepad for more intensive maneuvers, particularly turning around. If you want to fly in the opposite direction, you have to turn your head 180 degrees. Neither Oculus' store nor the game itself informs players that they should find a spinny chair or sit on a spacious couch. Let's not forget, after all, that Oculus Go limits recognized motion to 3DOF, which means any stand-and-spin maneuvers could trigger motion sickness when the VR world doesn't line up with your real-life motions.

Worth noting: unlike other major VR headsets, Oculus Go does not include a slider or scaler to adjust "interpupillary distance"—meaning, how images line up with your own face. One of our testers reports an above-average IPD of 69mm, and his comfort issues with misaligned images in the headset were a deal-breaker. The system's "glasses spacer," which pushes the screen a bit farther from your face to make room for bulky glasses, helped a little in his case, but not enough. Oculus representatives confirmed to Ars that the company has no plans to implement a software tweak for affected users.

For one, thanks to lenses getting in the way, we can't get a colorimeter pressed onto the screen and confirm an exact 200-nit brightness, which is standard for our device-battery tests. Additionally, I was unable to trick Go's combination of a face-proximity sensor and motion detector for the sake of our battery tests. My first stab involved employing our staff intern, as pictured above.

Thus, I'm more comfortable with an anecdotal "about two hours" estimate for a full Go battery, which was my standard recharge point while jumping among games, apps, and media players at Go's internal "66 percent" brightness setting (the device's factory default). Should you avoid 3D gaming during your full-battery session, you can add roughly 30 more minutes. In good news, at least, Go needs less than two hours to get back to 100-percent charge via its micro-USB charging port, which is a bit faster than expected for that ancient charging standard.

As a result, I can get through multi-episode marathons of TV shows while either lying down or sitting upright without any VR-related dizziness or back-to-reality unease. I needed a day to find the fit sweet-spot of clinging firmly to my face without pressing down too hard, at which point I found myself calling the weight and strap balance "good enough" for such use.

My favorite, gotta-tell-everyone Oculus Go experience came from its variety of media-streaming apps. I had the best time using Plex, an app that connects your library of digital audio and video to connected devices on your network—or outside your network in a pinch. Like other Go media players, it can translate 360-degree video to wrap around your full field of vision, or it can create a virtual screening room (which varies by app: theater, living room, on top of the Moon, and so on). Your interest in this use case will obviously vary; a virtual cinema is perhaps more interesting if you live in a crappy dorm or want to watch a movie on a plane.

Worth noting: I still regularly have "VR raccoon" prints pop up on my face after extended use, and friends with more hair, particularly women, reported more heat getting trapped inside the headset than I did.

Oculus Go, as seen in the above gallery, is a standalone VR headset with a single, one-handed controller. It weighs about a pound (470g) and comes with a cloth-and-elastic strap that wraps around the head. Even if you've never used a VR headset, this headstrap makes instant-fitting sense: pull it over the back of your head, and its full shape and support structure fleshes out.

Triangle road signmeaning

In 2000, devices like the Rio and Nomad rapidly cashed in on Napster fever, but high prices, low memory, and serious limitations littered the pre-iPod era. Yet I recall this time fondly because of one odd device: a portable CD player that could also read MP3s. I could burn a dozen albums onto a standard CD-R, then play it on an affordable Discman clone known as the Genica MPTrip (which, if you're wondering, I discovered on Ars Technica's forums).

Almost immediately, the Go makes its "sit-down" VR limitations apparent—and these are hard to ignore, whether you call yourself a VR connoisseur or a novice. Before breaking these down, let's talk about where Go fits in the consumer-headset ecosystem. In other words, some of Go's criticisms are honestly tempered by its holy-cow $199 price point for the 32GB model (or $249 for the 64GB one).

When you put the headset on, a face-sensor wakes the screen, and a prompt asks you to hold down the "menu" button on the Go controller. You'll do this every time to calibrate your forward-facing position and the relative position of your hand. Once your Go is unlocked, a floating menu of app and game icons appears in virtual space, and you use the Go controller as a pointing device to pick through content and menus. It also serves as a button-and-motion controller in any games and apps you load. All Go apps, free and paid, are downloaded from the Oculus Store, while the Chrome browser is also compatible with VR content (including 360-degree YouTube videos).

This is in contrast to pricier home-VR solutions like Oculus Rift, HTC Vive, and PlayStation VR, which add complications to the mix: wires, a host computer or console, button-loaded controllers, and attached tracking devices. (Rift and PSVR use RGB webcams, while Vive opts for dumber IR boxes that the headset itself recognizes.) Even if you select the cheapest option in that list, the PSVR (whose total required bundle starts at roughly $500), you're still in wires-and-camera territory. (Some Windows Mixed Reality sets don't require tracking boxes, at least, but the rest still applies.)

The hardware's grand result is still one step beyond "good enough," and Oculus' new, $199 product ships alongside a few standout apps to demonstrate its impressive-yet-affordable tech. Our top pick, Anshar Online, sums up nearly every impressive aspect while also confirming when Oculus Go tells you to Oculus Stop.

Go also includes Oculus' first stab at tiny, open-air speakers as the system default. This pair of speakers bounces low-volume sound off your skull, and the effect is impressive because of how quickly its novelty melts away. You'll want any reduction in bulk or ear-covering material that you can get for the sake of weight balance and heat dissipation, and Go delivers adequate sound without trapping your head. What's more, it employs delightful virtual-surround trickery, as I discovered in tests of Anshar Online, when I could hear laser blasts coming from behind me.

Chances are, these and other future Go games will have to shine in spite of limits, not because of them (think of the late '00s explosion of clever touchscreen arcade games). But Go wastes an opportunity to raise the control bar as a default, installed option—not even one additional action button! As a result, controls in games are likely going to feel pretty crappy for Oculus Go's short-term future.

Oculus Go differs from both of these camps in significant ways, but it more closely resembles the phone-based one. The difference there, of course, is that this headset is a pre-built, all-in-one product, so there's no phone-toaster requirement. But its origins as a smartphone-like device hide behind a few screws.

While we're nitpicking, Oculus Go requires connecting the headset to your existing smartphone and thus installing the Oculus app for the sake of setting Go up—even though Oculus Go's interface includes everything you need (settings panels, virtual keyboards) for the sake of filling out things like Wi-Fi passwords. For a device that promises "phone-free VR," it sure seems stupid of Oculus to immediately demand you get your phone out to jump into VR. This requirement also feels particularly tone-deaf in the wake of so much scrutiny over Facebook's apps and data permissions.

Instead, Go makes the dubious choice of maintaining this limited control default. Anshar is still satisfying within these limits, but it's hard to get around how quickly the game runs out of steam. It feels like a very polished tech demo. The same can be said for most of the Oculus Go's launch library, only with more bad news for anybody in search of comfortable sit-down VR games.

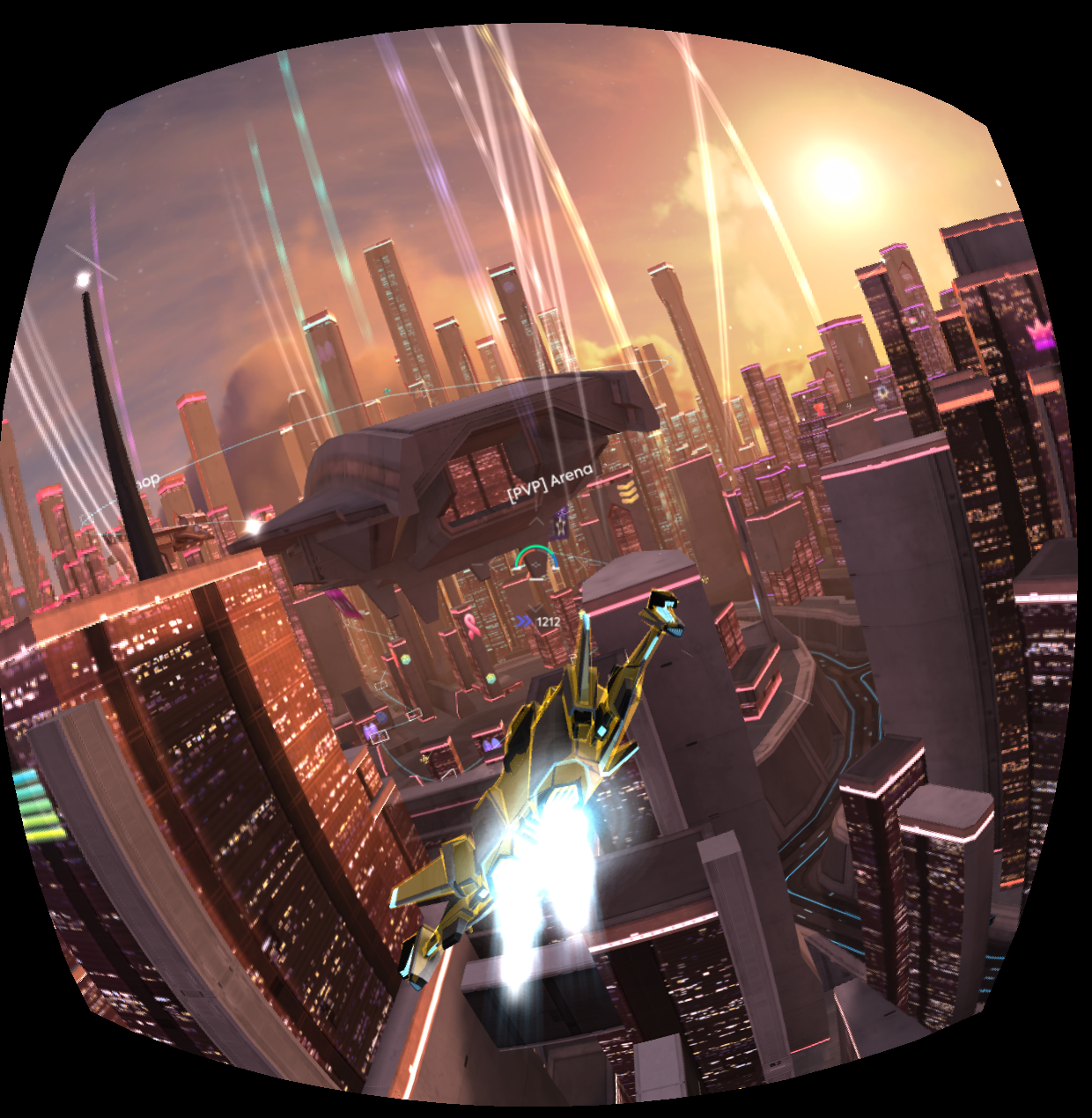

This game wowed us at the first Oculus Go preview event in March because it combined VR tricks with simple, action-packed gameplay and fluid 3D performance. Your mission: pilot a fighter jet around futuristic, Halo-like cities to either complete single-player missions or engage in online, multiplayer dogfights. To steer your jet, just look in any direction. Swipe the Go controller's touchpad to change your speed from full-blast to pause-and-hover, and tap its trigger button to shoot lasers. That's it. Fly and fight.

But you can't talk about a $199 VR device without appreciating what got its mix of quality and affordability across the finish line. Oculus Go wouldn't be where it is—incredible LCD performance, impressive skull-bouncing speakers, optimized 3D imagery, and a cleverly engineered cloth headstrap, all at a low price—without Facebook and Xiaomi's combined R&D muscle. When Mark Zuckerberg set a goal of getting "a billion people in VR" last year, he must have believed Oculus Go would launch in such an impressive fashion.

There also doesn't appear to be any support for local multiplayer connections should multiple friends own Go hardware and want to have a little VR party. Remember, the $200 price point was sweet enough for Game Boy and GBA owners to come together with link cables and local-multiplayer aspirations; Oculus would be wise to follow suit instead of forcing games and apps through their online matchmaking services.

That brings us to one massive pitfall in a budget-minded VR headset: a lack of ways to let nearby friends into the experience.

All of which is to say: I see two paths forward for privacy-conscious users. One: Oculus lightens up thanks to public pressure by putting the entire setup phase into the headset itself and giving users the freedom to leave their smartphones completely free of an unnecessary Oculus app and GPS-coordinates demand. Two: the Android development community delivers a custom, side-loaded launcher that lets users access legitimate Oculus Store software while sidestepping Oculus' current, overreaching requirements.

I spent 30 minutes looking for a manual override to this asinine GPS requirement and came up short. I have synced countless devices in the same space using nothing more than Bluetooth, and Oculus should be downright ashamed for overreaching this way. (Funnily enough, Go and the Oculus app work just fine if you go in and immediately disable the app's GPS access after the setup phase.)

The hardware's flat front doesn't just help with heat dissipation, by the way. Oculus Go is the only VR headset on the market right now with this design shape, which means you can just set it down flat on a table after a session. That's different from the likes of Rift, Vive, PlayStation VR, and other awkwardly shaped, cord-heavy designs. I've appreciated not having to anxiously and carefully balance this headset when putting it down between sessions.

Ms.Cici

Ms.Cici

8618319014500

8618319014500