Optical Flats - optical flatness testing

Carpenter, C. J. Cognitive dissonance, ego-involvement, and motivated reasoning. Ann. Int. Comun. Assoc. 43, 1–23 (2019).

Westfall, J., Van Boven, L., Chambers, J. R. & Judd, C. M. Perceiving political polarization in the United States: party identity strength and attitude extremity exacerbate the perceived partisan divide. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 145–158 (2015).

Jacoby, W. G. Is there a culture war? Conflicting value structures in American public opinion. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 108, 754–771 (2014).

Message framing has the potential to reduce polarization to the extent that it assuages ego- and group-justification motives by, for example, alleviating personal or collective insecurity, or taps into system-justification motives by appealing to patriotic traditions. However, some frames may increase polarization by eliciting ego- or group-defensiveness, accentuating categorical differences between groups, or highlighting individual and group differences in system-justifying (or system-challenging) attitudes. Unfortunately, there are often political incentives for partisan elites to exploit the more polarizing strategies of message framing to maximize support and turnout among their staunchest constituents.

Neal, Z. P. A sign of the times? Weak and strong polarization in the US Congress, 1973–2016. Soc. Netw. 60, 103–112 (2020).

Carmines, E. G. & Woods, J. The role of party activists in the evolution of the abortion issue. Polit. Behav. 24, 361–377 (2002).

In summary, ideological and issue polarization, partisan alignment, and affective polarization (like all other outcomes of social influence) depend on who, what and how, that is, the source of communication, the particulars of the message and the channel or platform of transmission20,188,189,190. Some factors increase polarization, as when highly polarized elites stoke issue, ideological and affective polarization among voters, or when restrictive framing of nationalist messages increases partisan or ideological alignment with respect to immigration or foreign policy. Other variables contribute to depolarization, as when strategic framing of environmental values, activation of system justification motives at the national level, and sympathetic narratives about immigrants bring liberals and conservatives closer together (at least temporarily).

In summary, ego, group and system justification mechanisms contribute to ideological and issue polarization, partisan alignment and affective polarization. Those who endorse liberal and conservative attitudes exhibit ego- and group-justifying biases favouring themselves and the groups to which they belong, contributing to symmetric forms of polarization99,140. However, they differ in terms of system-justifying (versus system-challenging) motives, which might help to explain asymmetric polarization10,34,47,48,73,74.

Observation with a magnifying power of 20x or more is usually accomplished by a compound microscope, which is composed of an objective lens and an eye-piece separated by a definite distance. The objective lens forms a magnified but inverted real image of the object under inspection, and the eye-piece, which is a special kind of magnifier, further magnifies the real image. Thus the compound microscope can be compared to a two- step amplifier, wheras a magnifier is considered as a single-step one. Hence the former can have a very high magnifying power, such as 100x to 1000x; and when used at low magnifying power of 20x to 30x, it has a wider image field and a longer working distance than a magnifier with the same magnifying power

Knuckey, J. & Hassan, K. Authoritarianism and support for Trump in the 2016 presidential election. Soc. Sci. J. 59, 47–60 (2022).

Isom, D. A., Mikell, T. C. & Boehme, H. M. White America, threat to the status quo, and affiliation with the alt-right: a qualitative approach. Sociol. Spect. 41, 213–228 (2021).

Porat, R., Tamir, M., Wohl, M. J., Gur, T. & Halperin, E. Motivated emotion and the rally around the flag effect: liberals are motivated to feel collective angst (like conservatives) when faced with existential threat. Cogn. Emot. 33, 480–491 (2019).

Bond, R. M. et al. A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature 489, 295–298 (2012).

Morisi, D., Jost, J. T., Panagopoulos, C., & Valtonen, J. Is there an ideological asymmetry in the incumbency effect? Evidence from US Congressional elections. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211046830 (2022).

Cowan, S. K. & Baldassarri, D. “It could turn ugly”: selective disclosure of attitudes in political discussion networks. Soc. Netw. 52, 1–17 (2018). Using a novel set of survey questions, this research illustrates the mechanism of selective disclosure: the tendency to withhold political attitudes from those with whom one disagrees in an attempt to avoid conflict.

Importantly, individuals play an active part in selecting and navigating their social networks. Much network homophily — the tendency for people to associate with similar others — is based on socio-demographic characteristics (such as race, education, income, age and gender). At the same time, there is evidence that ideological and partisan considerations inform the choice of friends, as well as business and romantic partners218,219,220,221. It is not entirely clear whether people are explicitly choosing interaction partners on the basis of political considerations or whether ideological homophily is a byproduct of associational patterns rooted in socio-demographic similarities59. This is an important question because the implications for polarization differ.

Kriesi, H. et al. Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: six European countries compared. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 45, 921–956 (2006).

Iyengar, S. & Hahn, K. S. Red media, blue media: evidence of ideological selectivity in media use. J. Commun. 59, 19–39 (2009).

Jost, J. T., Hennes, E. P. & Lavine, H. in The Oxford Handbook of Social Cognition (ed. Carlston, D. E.) 851–875 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Kinder, D. R. & Kalmoe, N. P. Neither Liberal Nor Conservative: Ideological Innocence In The American Public (Univ. Chicago Press, 2017).

Guess, A. & Coppock, A. Does counter-attitudinal information cause backlash? Results from three large survey experiments. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 50, 1497–1515 (2020).

Krupnikov, Y. & Ryan J. B. The Other Divide: Polarization And Disengagement In American Politics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Crowson, H. M. & Brandes, J. A. Differentiating between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton voters using facets of right-wing authoritarianism and social-dominance orientation: a brief report. Psychol. Rep. 120, 364–373 (2017).

DiMaggio, P., Evans, J. & Bryson, B. Have Americans’ social attitudes become more polarized? Am. J. Sociol. 102, 690–755 (1996).

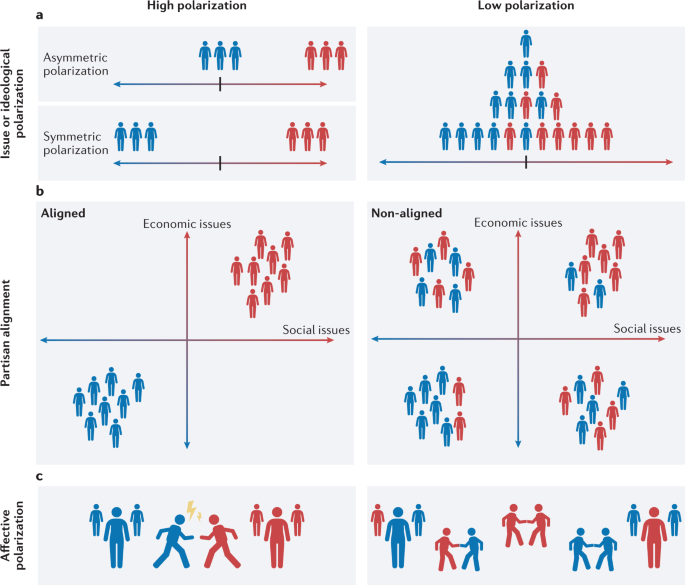

a | High issue/ideological polarization occurs when one (asymmetric) or both groups (symmetric) move towards the extremes and away from the centre with respect to issues and/or ideology. There is low issue/ideological polarization when most people hold moderate positions and there is considerable overlap between groups. b | Partisan issue alignment occurs when groups neatly divide over many issues. Low alignment occurs when the issue preferences of various segments of society are crosscutting. c | Affective polarization occurs when members of different groups (or parties) hold starkly positive feelings about members of their own group and/or starkly negative feelings about members of the other group(s).

Abramowitz, A. I. The Great Alignment: Race, Party Transformation, and the Rise of Donald Trump (Yale Univ. Press, 2018).

Lees, J. & Cikara, M. Inaccurate group meta-perceptions drive negative out-group attributions in competitive contexts. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 279–286 (2020).

Stronger evidence that affective polarization can generate issue polarization comes from a study demonstrating that out-party animus measured prior to the COVID-19 outbreak was a strong predictor of issue polarization concerning ‘stay-at-home’ orders and other pandemic-related policies, even after adjusting for partisanship15. Furthermore, partisanship exacerbates issue-based conflict27, and party activists are capable of pushing candidates to take more extreme positions on issues over time37. Strongly identified partisans (who tend to be affectively polarized) exhibit more alignment than weakly identified partisans38. Moreover, longitudinal research demonstrated that ideological consistency at time 1 predicted affective polarization at time 2, and affective polarization at time 1 predicted ideological consistency at time 2, all other things being equal82,87.

Hobolt, S. B., Leeper, T. J. & Tilley, J. Divided by the vote: affective polarization in the wake of the Brexit referendum. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 1476–1493 (2021).

Cross-national comparisons of political polarization are complicated by variations in political systems and cleavage alignments. In the USA, there are three major cleavages on economic, civil rights and moral issues, with the moral dimension largely crosscutting the other two dimensions40,77. In European countries, there are longstanding territorial, religious and social class cleavages and more recent cleavages pertaining to globalization and integration with the European Union333,334. Despite these differences, the cognitive–motivational and social-communicative processes that contribute to polarization seem to be largely the same in the USA and Europe.

Much has been written about how Internet and social media platforms exacerbate political polarization70,127,231,255,256,257,258,259,260,261,262,263. Personalized machine-learning algorithms and the freedom to choose content tend to increase the likelihood of selective information exposure to previously unimaginable levels. Thus, many worry that social media platforms are merely becoming ideological echo chambers in which people who are strongly motivated by ego-justifying, group-justifying or system-justifying (or system-challenging) goals seek out like-minded others261,264,265. At the same time, it is important to bear in mind that patterns of online ideological segregation resemble offline patterns of media consumption205, and most social media users are exposed to reasonable levels of ideological heterogeneity206,207,257,266,267,268.

Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J. & Newman, B. Intellectual humility in the sociopolitical domain. Self Identity 19, 989–1016 (2020).

Jost, J. T., van der Linden, S., Panagopoulos, C. & Hardin, C. D. Ideological asymmetries in conformity, desire for shared reality, and the spread of misinformation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 23, 77–83 (2018). From the perspective of system justification theory, this article reviews evidence of ideological asymmetry such that conservatives prioritize conformity, possess a stronger desire for a shared reality with those who share their ideology, and maintain more homogeneous networks, compared to liberals.

Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y. & Ryan, J. B. Affective polarization or partisan disdain? Untangling a dislike for the opposing party from a dislike of partisanship. Public. Opin. Q. 82, 379–390 (2018).

Van Boven, L., Judd, C. M. & Sherman, D. K. Political polarization projection: social projection of partisan attitude extremity and attitudinal processes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 103, 84 (2012).

It may usually be impossible to realize this condition exactly, but the nearer the eye is brought to the magni- fier, the more closely the magnifying power takes a value given by the above formula. Hence the magnifying power of a 300 mm magnifier will be approximately (1 + 0.83) or 1.83x, and that one of a 250 mm one will be about (1 + 1.0) or 2x. This means that the magnifying power of a magnifier is always greater than 1x, however weak it may be, as long as it is used under the condition stated above. The medium power magnifier with a normal magnifying power of 5x or 7x can also have a magnifying power of nearly 6x or 8x respectively if used under the above condition. To realize this condition, hold the magnifier with one hand and keep it as close as possible to your eye, while adjusting the position of the object under in- spection with the other hand until the magnified virtual image can be observed sharply. This is the second basic point about using magnifiers.

Vegetti, F. The political nature of ideological polarization: the case of Hungary. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 681, 78–96 (2019).

However, there is clearly a market for political misinformation255, and technology companies such as Twitter and Facebook profit from the spread of ‘fake news’, which increases customer engagement and therefore advertising revenue256. These market incentives both reflect and exacerbate ideological and affective forms of polarization, insofar as emotionally charged material, such as that which is contemptuous of ideological adversaries, is more likely to go ‘viral’ than more measured types of political discourse260,263,269,270.

Brown, J. R. & Enos, R. D. The measurement of partisan sorting for 180 million voters. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 998–1008 (2021).

Mijs, J. J. The paradox of inequality: income inequality and belief in meritocracy go hand in hand. Socioecon. Rev. 19, 7–35 (2021).

McCarty, N., Poole, K. T. & Rosenthal, H. Polarized America: the Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches (MIT Press, 2016).

Martinez, J. E., Feldman, L. A., Feldman, M. J. & Cikara, M. Narratives shape cognitive representations of immigrants and immigration-policy preferences. Psychol. Sci. 32, 135–152 (2021).

Jacquet, J., Dietrich, M. & Jost, J. T. The ideological divide and climate change opinion: “top-down” and “bottom-up” approaches. Front. Psychol. 5, 1458 (2014).

Pew Research Center. Large majority of the public views prosecution of capitol rioters as ‘very important’. Pew Research https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/03/18/large-majority-of-the-public-views-prosecution-of-capitol-rioters-as-very-important/ (2021).

In this Review we have imposed conceptual structure on a vast and rapidly growing but fragmented, multi-disciplinary body of scholarship on political polarization. Specifically, we reviewed evidence concerning the effects of cognitive–motivational mechanisms (ego-justification, group-justification and system-justification) in social-communicative contexts (as a function of source, channel and message factors) on three different operationalizations of political polarization (ideological/issue separation, partisan alignment and affective polarization). Unfortunately, the empirical literature has not advanced to the point that it is possible to hypothesize with precision how any given attempt at political communication will interact with cognitive–motivational mechanisms in specific social-communication contexts to influence polarization or depolarization. We have nonetheless identified the key variables that scholars may use in determining when various types of polarization are likely to arise and — if they deem the situation problematic — in devising depolarization interventions.

Grossmann, M. & Thaler, D. Mass–elite divides in aversion to social change and support for Donald Trump. Am. Polit. Res. 46, 753–784 (2018).

Lee, S., Rojas, H. & Yamamoto, M. Social media, messaging apps, and affective polarization in the United States and Japan. Mass. Commun. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2021.1953534 (2021).

Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. in Cognitive Dissonance: Reexamining a Pivotal Theory in Psychology 3–24 (American Psychological Association, 2019).

Descriptive social norms about what other people think or do and injunctive norms about what people ought to think or do are two major sources of social influence322. Both can lead partisans to feel socially pressured to hold particular opinions or enact certain behaviours. In one experiment, Republicans received a message indicating that a clear majority of fellow Republicans agreed that the climate is changing and are taking action to combat climate change. These individuals — relative to those who did not receive this message — were more likely to report believing in climate change and to have climate-friendly intentions323,324. In this case, information about descriptive norms served to reduce issue polarization concerning climate change, but the effects generally depend upon the message and topic.

For political polarization (or depolarization) to occur, the cognitive–motivational mechanisms described above must play out in some social or political context61. To systematize our discussion of social-communicative contexts we invoke McGuire’s188 communication/persuasion matrix, which distinguishes among source, message, channel, receiver and target (or destination) characteristics as determinants of social influence20,189,190. A guiding assumption of this general approach is that the kinds of cognitive and motivational mechanisms described above play mediating (or, in some cases, moderating) roles in explaining, for instance, whether specific messages communicated by certain sources are persuasive — or, in the present context, serve to increase or decrease political polarization.

Third, disentangling the myriad effects of competing social influences on political polarization will require careful attention to the cognitive and motivational mechanisms that mediate message reception. It is usual to offer psychological speculations, such as the supposition that partisan communication activates group-justifying motives or that conservative communication activates system-justifying motives — and we have engaged in such speculation here. However, few (if any) studies actually connect the dots (see, for example, critiques of existing research on motivated political reasoning103,300,301). This is a critical step for drawing definitive conclusions about how specific independent variables influence the three types of political polarization discussed here.

The concept of polarization is also used to characterize states or trends in the conditions of intergroup relations. That is, polarization may refer to a large or increasing gap between two or more groups. This has clear relevance to politics, which often involves group-level competition over policy issues and/or ideologies. For example, there is a strong consensus among scholars of politics in the USA that liberal and conservative political elites (including members of Congress, party activists, donors and judicial appointees) have grown increasingly polarized over the past few decades27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. At the same time, the extent to which elite-level polarization has influenced the belief systems of ordinary citizens remains a matter of debate8,27,35,36,37,38,39,40.

Halliez, A. A. & Thornton, J. R. Examining trends in ideological identification: 1972–2016. Am. Polit. Res. 49, 259–268 (2021).

being independent of the distance between the magnifier and the eye. From the formula it is easily calculated that a magnifier with a 25 mm focal length has a normal magnifying power of 10x, and one with a 50 mm focal length has 5x normal magnifying power It can be seen also that the normal magnifying power of a „weak“ magnifier with a 250 mm focal length is 1.0x, meaning that no benefit can be obtained by using such a magnifier. Furthermore, a weaker one with a 300 mm focal length has a normal magnifying power of 0.83x, which means that the size of the virtual image viewed through it is smaller than that of the objekt viewed with the naked eye at a distance of 250 mm! These results are absolutely correct so far as the „normal magnifying power“ is concerned.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G. & Lelkes, Y. Affect, not ideology: a social identity perspective on polarization. Public. Opin. Q. 76, 405–431 (2012).

Azevedo, F. & Jost, J. T. The ideological basis of anti-scientific attitudes: effects of authoritarianism, conservatism, religiosity, social dominance, and system justification. Group Process. Interg. Relat. 24, 518–549 (2021).

Some studies suggest that social media platforms are frequently used to spread out-group animosity, thereby exacerbating affective polarization261. For example, an analysis of nearly 600,000 Facebook posts and more than 200,000 Twitter posts by media outlets on the political left (such as the New York Times and MSNBC) and political right (such as Fox News and Breitbart) found that posts mentioning the political in-group were shared more often than other posts (with estimated increases in diffusion rate ranging from 0% to 37%). However, posts mentioning the out-group were even more likely to be shared (with estimated diffusion rate increases ranging from 29% to 57%260). Sentiment analysis of messages about the out-group revealed that they frequently expressed negative emotions such as anger, moral outrage and mockery. A follow-up study of more than 800 Facebook posts and a million Twitter posts from the official accounts of members of the US Congress showed that messages mentioning the out-group, but not the in-group, were more likely to be shared than other posts (increased diffusion rates ranging from 58% to 180%260). Retweets often included anger-related language260; this is important because anger inflames political polarization by, among other things, increasing cognitive oversimplification and categorical thinking that divides ‘us’ and ‘them.’132.

Cohen, G. L. Party over policy: the dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 808–822 (2003).

Stewart, A., McCarty, N. & Bryson, J. Polarization under rising inequality and economic decline. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd4201 (2020).

Framing occurs whenever a political actor (such as a candidate or opinion leader) highlights a subset of relevant considerations about an issue, candidate or event, leading their audience members to think about the topic in a particular way273,274,275. Several studies show that stressing certain values can change support for specific issues. For example, framing environmental issues in terms of conservative values such as purity, sanctity, commerce or patriotism might lead conservatives to express more support for pro-environmental legislation275,276,277,278,279. Abstract rhetoric used by in-group members may also increase alignment between values and identities. For instance, Republican elite discourse has for decades emphasized traditional family values and resistance to social change, and this seems to have increased the correlation between partisanship and ideology more steeply among Republican than Democratic voters47.

Mellers, B., Tetlock, P. & Arkes, H. R. Forecasting tournaments, epistemic humility and attitude depolarization. Cognition 188, 19–26 (2019).

Ashokkumar, A. et al. Censoring political opposition online: who does it and why. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 91, 104031 (2020). This study finds that supporters of a political cause (such as abortion restriction or gun control) recommend deleting ideologically incongruent messages and banning sources of ideologically incongruent messages, even when messages are inoffensive.

Message frames can shift the salience of group identities and therefore the basis for group-justification. For example, Democratic parents express very different social and political attitudes when their status as parents (as compared to their status as Democrats) is made salient280. The parental frame resulted in issue depolarization: Democrats expressed attitudes that were more similar to those of Republicans when their parental identification was made salient compared to various other experimental conditions (such as when their partisan identity was made salient). Likewise, emphasizing a superordinate national identity can reduce out-group animus as well as affective and ideological polarization281,282,283, consistent with social identity theory90,92,139.

In terms of research interventions, reducing ego-defensiveness by encouraging people to affirm positive things about themselves sometimes helps to reduce information-processing biases129,130. Other intervention strategies focus on correcting misperceptions, encouraging more complex thinking, and reducing anger and competitive feelings26,131,132. Some of these techniques (reducing anger and competition) might reduce ego-defensive motivation itself, whereas others (correcting misperceptions) seek to undo the consequences of ego-defensive processing. However, the latter run the risk of provoking additional efforts at ego-justification if they are not implemented carefully and subtly133,134. Finally, cultivating a spirit of intellectual humility (responding generously and humbly towards others) could help to reduce political polarization by reducing ego-defensiveness135,136,137,138. However, these studies focused on relatively short-term changes; more research is needed to develop interventions that promote lasting forms of change.

Stern, C. & Crawford, J. T. Ideological conflict and prejudice: an adversarial collaboration examining correlates and ideological (a)symmetries. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 12, 42–53 (2021).

Nature Reviews Psychology thanks Jeff Lees, Konstantin Vossing and Leor Zmigrod for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Azevedo, F., Jost, J. T. & Rothmund, T. “Making America great again”: system justification in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 3, 231–240 (2017).

Lau, R. R., Anderson, D. J., Ditono, T. M., Kleinberg, M. S. & Redlawsk, D. P. Effect of media environment diversity and advertising tone on information search, selective exposure, and affective polarization. Polit. Behav. 39, 231–255 (2017).

Druckman, J. N. A framework for the study of persuasion. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 25, 65–88 (2022). This review provides a framework for drawing generalization from research on persuasion, focusing on the actors (speakers and receivers), treatments (topics, content and media), outcomes (attitudes, behaviours, emotions and identities) and settings (competition, space, time, process and culture).

Kubin, E., Puryear, C., Schein, C. & Gray, K. Personal experiences bridge moral and political divides better than facts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2008389118 (2021).

Social psychologists have long argued that people are driven to maintain or enhance cognitive consistency and congruence among beliefs, opinions and values108,109. Consistent with this argument, there is abundant evidence that since the 1960s those who endorse liberal attitudes have increasingly joined the Democratic Party, and those who endorse conservative attitudes have increasingly joined the Republican Party35,110. Consequently, the correlation between partisanship and ideology has risen from roughly r = 0.4 in 1988 to r = 0.6 in 2012 (refs.47,91). From a psychological perspective, the increasing alignment between relational (or identity-based) and ideological commitments could reflect a reduction in cognitive dissonance. That is, to maintain the integrity of their self-concept, people seek to reduce inconsistencies between self-categorization as a good group member, on one hand, and important beliefs, opinions and values, on the other. From a more macro-political perspective, increased alignment between partisanship and ideology reflects a ‘sorting’ process that increases intergroup conflict35,38,77.

Mudde, C. Fighting the system? Populist radical right parties and party system change. Party Politics 20, 217–226 (2014).

Hart, P. S., Feldman, L., Leiserowitz, A. & Maibach, E. Extending the impacts of hostile media perceptions: influences on discussion and opinion polarization in the context of climate change. Sci. Commun. 37, 506–532 (2015).

Polarization of light

Likewise, ideological polarization in general — not just on specific issues or values — can drive affective polarization. In a large-scale experiment, participants read about two hypothetical political candidates who were represented as either slightly liberal and slightly conservative (in the convergent condition) or as very liberal and very conservative (divergent condition). In feeling thermometer ratings, participants were more affectively polarized in the divergent condition, expressing more warmth towards the more extreme candidate whose ideology they shared and less warmth towards the more extreme candidate whose ideology they did not share. This effect was stronger for participants who were more interested in politics and more ideologically extreme themselves83. Another series of experiments demonstrated that learning about policy disagreements between rank-and-file Democrats and Republicans made partisan identities more salient and caused participants to express more warmth towards in-party members and less warmth towards out-party members81.

Kalla, J. L. & Broockman, D. E. Reducing exclusionary attitudes through interpersonal conversation: evidence from three field experiments. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 114, 410–425 (2020).

As noted above, ‘us versus them’ dynamics can result in stereotyping and false or exaggerated beliefs about the out-group132,146,147,148,149. In one study, Republicans overestimated the percentage of Democrats who were LGBTQ by 25 points, whereas Democrats overestimated the percentage of Republicans who were evangelicals by 20 points150. By exaggerating the prototypical characteristics of out-group members in these ways, ideologues increase the perceived social distance between different groups and might stereotype, discredit or marginalize the out-group. Partisans might also represent their adversaries as more obstructionist95, more ideologically extreme122,151,152,153, more prejudiced against the in-group55, or more violent154 than they actually are. Presumably, distorting images of the out-group as deviant, hostile, stubborn, extreme and unreasonable serves to justify treating the out-group unfavourably55,89,95,155.

Mullinix, K. J. Partisanship and preference formation: competing motivations, elite polarization, and issue importance. Polit. Behav. 38, 383–411 (2016).

Pierson, P. & Schickler, E. Madison’s constitution under stress: a developmental analysis of political polarization. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 23, 37–58 (2020).

Stanley, M. L., Henne, P., Yang, B. W. & De Brigard, F. Resistance to position change, motivated reasoning, and polarization. Polit. Behav. 42, 891–913 (2020).

Baldassarri, D. & Park, B. Was there a culture war? Partisan polarization and secular trends in US public opinion. J. Polit. 82, 809–827 (2020). This analysis of trends in public opinion in the USA over time finds partisan polarization on economic and civil rights issues, whereas opinions on moral issues followed a trend of secularization. Both Democrats and Republicans have increasingly adopted more progressive moral views, but Republicans changed their views more slowly than Democrats.

Brewer, M. B. in The Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of Prejudice (eds Sibley, C. G. & Barlow, F. K.) 90–110 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2017).

Voelkel, J. G. et al. Interventions reducing affective polarization do not improve anti-democratic attitudes. Nat. Hum. Behav. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/7evmp (2021).

Representations of nationalism and national identification might serve as ‘master frames’ that shape collective self-understanding285,286. Prior to 2000, Democrats and Republicans differed little in terms of nationalist beliefs, but as of 2016 they held very different conceptions, apparently because of 9/11, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and racial resentment in response to Barack Obama’s presidency286. By framing patriotism in politically conservative terms, Republican elites appear to have increased the alignment between Republican partisanship and nationalist values. Experimental studies suggest that increasing system justification motivation may, in some cases, raise the national attachment levels of people who hold liberal views so that they more closely resemble those of people who hold conservative views, thereby temporarily reducing polarization on issues of patriotism — but not nationalism, defined as an attitude of superiority towards other countries282,287,288,289.

van der Linden, S., Panagopoulos, C., Azevedo, F. & Jost, J. T. The paranoid style in American politics revisited: an ideological asymmetry in conspiratorial thinking. Polit. Psychol. 42, 23–51 (2021).

Polarization examples

Barberá, P. in Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field (eds Persily, N. & Tucker, J.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2020).

Kingzette, J. et al. How affective polarization undermines support for democratic norms. Public Opin. Q. 85, 663–677 (2021).

Drummond, C. & Fischhoff, B. Does “putting on your thinking cap” reduce myside bias in evaluation of scientific evidence? Think. Reason. 25, 477–505 (2019).

Huddy, L. & Yair, O. Reducing affective polarization: warm group relations or policy compromise? Polit. Psychol. 42, 291–309 (2021).

Hacker, J. & Pierson, P. in Solutions to Political Polarization in America (ed. Persily, N.) 59–70 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2015).

Archival research reveals that mainstream media coverage of Democratic elites’ support for climate action stimulated resistance and even backlash (decreased support) among Republican voters144. Likewise, exposure to same-party and other-party messages on partisan media platforms often increases affective polarization, in the latter case because of resistance to change and the spontaneous generation of counterarguments249. Thus, out-party cues often repel citizens while in-party cues tend to attract them. In this way, ego- and group-justifying motives exacerbate issue polarization when viewers are aware of partisan or ideological disagreement. Such circumstances also make individual and group differences in system justification motivation more predictive of political behavior and more salient to political actors by drawing attention to the fact that some people are driven to defend the status quo while others are driven to challenge it101,107,171,172,250,251,252.

Elite signals are typically communicated to citizens through mass media channels that have changed immensely since the advent of cable television and the ideological segmentation of news content238. Politically engaged viewers, who are more attentive to elite cues191, have increasingly tuned into cable and Internet news sources239,240,241,242, while others have dropped out243,244. Exposure to ideologically driven networks (such as Fox News on the political right and MSNBC on the political left) exerts both persuasive245,246 and reinforcement effects247. The former occurs when, for instance, Independents who view Fox News are convinced to support a Republican candidate. The latter occurs when Republicans who view Fox News become even more likely to vote for a Republican candidate. Partisan media exposure also increases issue polarization, especially among viewers who are already fairly extreme in their views248.

Partisan alignment can also influence affective polarization. For example, citizens who take more issue positions on the same side of the ideological spectrum as their party (that is, are more aligned) exhibit more out-group animus and affective polarization, adjusting for many other factors84.

Brown, J. R., Enos, R. D., Feigenbaum, J. & Mazumder, S. Childhood cross-ethnic exposure predicts political behavior seven decades later: evidence from linked administrative data. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe8432 (2021).

Mernyk, J. S., Pink, S. L., Druckman, J. N. & Willer, R. Correcting inaccurate metaperceptions reduces Americans’ support for partisan violence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2116851119 (2022).

Druckman, J. N., Levendusky, M. S. & McLain, A. No need to watch: how the effects of partisan media can spread via inter-personal discussions. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 62, 99–112 (2018).

Ditto, P. H. et al. At least bias is bipartisan: a meta-analytic comparison of partisan bias in liberals and conservatives. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 14, 273–291 (2019).

Hennes, E. P., Ruisch, B. C., Feygina, I., Monteiro, C. A. & Jost, J. T. Motivated recall in the service of the economic system: the case of anthropogenic climate change. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 145, 755–771 (2016).

Ashokkumar, A., Galaif, M. & Swann, W. B. Jr Tribalism can corrupt: why people denounce or protect immoral group members. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 85, 103874 (2019).

Additional cognitive–motivational mechanisms that may exacerbate issue polarization include other forms of reduction in cognitive dissonance, such as selective avoidance of counter-attitudinal information and motivated resistance to attitude change (see Table 1), both of which reflect ego-defensive motives to avoid inconsistency and maintain the individual’s pre-existing beliefs, opinions and values100,123,124,125,126. For instance, Republicans who were consistently exposed to messages from a liberal Twitter bot exhibited backlash, expressing even more conservative opinions as a result127. This suggests the presence of ego-defensiveness: Republicans were not merely indifferent to liberal messaging but actively sought to combat it or to compensate for its anticipated effects. Exposure to a conservative bot did not meaningfully affect Democrats in this study. Other studies suggest that people might engage in counterfactual thinking about ‘what might have been’ in a creative but self-serving (or group-serving) manner in order to maintain their own pre-existing attitudes. For example, Donald Trump supporters felt that it was less unethical to spread the falsehood that more people attended Trump’s presidential inauguration than Barack Obama’s presidential inauguration after pondering the counterfactual possibility that “If security had been less tight at Trump’s inauguration, then more people would have attended it than Obama’s inauguration,” compared to an experimental condition in which this counterfactual was not raised128. Thus, people may rationalize the spread of misinformation through the biased use of information about ‘what might have been’.

Goya-Tocchetto, D., Kay, A. C., Vuletich, H., Vonasch, A. & Payne, K. The partisan trade-off bias: when political polarization meets policy trade-offs. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 98, 104231 (2022).

Arceneaux, K. & Johnson, M. Changing Minds or Changing Channels? Partisan News in an Age of Choice (Univ. Chicago Press, 2013).

Van Bavel, J. J. & Packer, D. The Power of Us: Harnessing Our Shared Identities to Improve Performance, Increase Cooperation, and Promote Social Harmony (Little Brown Spark, 2021).

Groenendyk, E. & Krupnikov, Y. What motivates reasoning? A theory of goal-dependent political evaluation. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 65, 180–196 (2021).

Duckitt, J. A dual-process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 33, 41–113 (2001).

The ideological homogeneity of social networks is enhanced by structural dynamics such as geographic sorting209,210,211, the growing politicization of the rural–urban divide212,213, and ‘lifestyle’ differences that are correlated with political orientation107,214,215,216 (see also Box 1). These geographic and cultural divisions are likely to limit exposure to ‘the other side’, especially among individuals who hold more conservative attitudes and are less open to new or different experiences217.

Pronin, E., Lin, D. Y. & Ross, L. The bias blind spot: perceptions of bias in self versus others. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 28, 369–381 (2002).

Jost, J. T. et al. How social media facilitates political protest: information, motivation, and social networks. Polit. Psychol. 39 (suppl. 1), 58–118 (2018).

Womick, J., Rothmund, T., Azevedo, F., King, L. A. & Jost, J. T. Group-based dominance and authoritarian aggression predict support for Donald Trump in the 2016 US presidential election. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 10, 643–652 (2019).

Finkel, E. J. et al. Political sectarianism in America. Science 370, 533–536 (2020). This article discusses the causes and consequences of a concept related to affective polarization — political sectarianism — which involves othering, aversion and moralization.

Hargittai, E., Gallo, J. & Kane, M. Cross-ideological discussions among conservative and liberal bloggers. Public Choice 134, 67–86 (2008).

Hetherington, M. & Weiler, J. Prius Or Pickup? How The Answers To Four Simple Questions Explain America’s Great Divide (Houghton Mifflin, 2018).

Lelkes, Y. Affective polarization and ideological sorting: a reciprocal, albeit weak, relationship. Forum 16, 67–79 (2018).

Lelkes, Y., Sood, G. & Iyengar, S. The hostile audience: the effect of access to broadband internet on partisan affect. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 61, 5–20 (2017).

Cialdini, R. B., Levy, A., Herman, C. P. & Evenbeck, S. Attitudinal politics: the strategy of moderation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 25, 100–108 (1973).

Lipset, S. M. & Rokkan, S. in Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives 1–64 (The Free Press, 1967).

Bayes, R., Druckman, J., Goods, A. & Molden, D. C. When and how different motives can drive motivated political reasoning. Polit. Psychol. 41, 1031–1052 (2020).

Levendusky, M. & Malhotra, N. (Mis)perceptions of partisan polarization in the American public. Public Opin. Q. 80, 378–391 (2016).

Many people avoid interpersonal conflict, which can be ego-damaging, without permanently modifying their social network. For example, during close election campaigns, people eschew political conversations with adversaries by skipping family reunions or shortening Thanksgiving dinners231. When contact is unavoidable, people engage in selective disclosure232,233. That is, they simply withhold their attitudes from people with whom they expect to disagree. This could result in pluralistic ignorance (an exaggerated appearance of homogeneity) because only certain political views are expressed, and disagreement is suppressed233,234,235,236. Thus, even among people who maintain reasonably heterogeneous online and offline relationships, ego-defensive mechanisms such as selective disclosure145 (and selective censorship) could undermine the depolarizing potential of these networks. These mechanisms might also reinforce in-group norms by concealing within-group variability, potentially exacerbating other forms of alignment and polarization143,237.

Fiorina, M. P., Abrams, S. J. & Pope, J. C. Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America 3rd edn (Pearson Longman, 2010).

It is especially important to distinguish between states and trends when studying polarization in cross-national contexts. For example, there is evidence that ideological, issue and affective polarization have increased rapidly in the USA in the past few decades339,340, but it is also true that levels of polarization in the USA are smaller than (or similar to) levels observed in other countries65,341. Historically speaking, polarization in the USA reflects social patterns that began with Southern realignment following civil rights legislation, the rise of single-issue interest groups, changes in campaign finance law, and the withdrawal of moderates from party politics and primary races, especially on the political right10,27,31,34,37,72,342,343). By contrast, the rise of polarization in Europe is largely attributed to anti-establishment movements and newly founded populist parties67,344,345.

Morgeson, F. V. III, Sharma, P. N., Sharma, U. & Hult, G. T. M. Partisan bias and citizen satisfaction, confidence, and trust in the US Federal Government. Public Manag. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1945667 (2021).

The compound microscope does however have some disadvantages; it is massive and expensive, the object under inspection must be placed on its stage, and the observed magnified image is inverted. Here one sees the advantage of having 20x to 30x magnifiers, which make possible the observation of the erect (i.e. not inverted) image of each part of a large object that cannot be laid on the microscope stage. Such magnifiers are indispen- sable, for instance, in photo-mechanical processes. These high magnifying power magnifiers, however, have a very short working distance, and further, the opti- cal axis of the observer’s eye must coincide correctly with that of the magnifier. This latter condition requires some experience on the part of the user, and incorrect use of these magnifiers prevents the user from taking full advantage of their performance. It should be emphasized again that one should carefully select the magnifying power of magnifiers, now available from about 2x to 30x.

Broockman, D. E., Kalla, J. L. & Westwood S. J. Does affective polarization undermine democratic norms or accountability? Am. J. Polit. Sci. (in the press).

Because issue and affective polarization have increased most among demographic groups (such as the elderly) that are less likely to use the internet and social media platforms, the authors of one study272 concluded that social media was unlikely to be a major driver of polarization. However, this conclusion was based on a design in which individual social media usage was not measured or manipulated, and so could be subject to the ecological fallacy (drawing inappropriate inferences about individual behavior on the basis of aggregate trends261).

Hogg, M. A., Turner, J. C. & Davidson, B. Polarized norms and social frames of reference: a test of the self-categorization theory of group polarization. Basic. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 11, 77–100 (1990).

Rogers, N. & Jost, J. T. Liberals as cultural omnivores. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 7, 255–265 (2022). This analysis reveals that self-identified liberalism was positively associated with the total number of cultural exposures across a wide range of domains. The ideological asymmetry in cultural sorting was statistically mediated by individual differences in openness to new experiences.

Boxell, L., Gentzkow, M. & Shapiro, J. M. Greater internet use is not associated with faster growth in political polarization among US demographic groups. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 10612–10617 (2017).

Political communication often takes a narrative format in which events are described in chronological order alongside information about key characters and their actions190,291. Many of these narratives provide moral lessons or takeaways292. For instance, narratives about marginalized groups, such as struggle-oriented stories about immigrants, can counteract system justification tendencies that might otherwise discount or disparage immigrants’ experiences293,294,295. In addition, giving people an opportunity to participate in a ‘non-judgemental exchange of narratives’ was found to increase feelings of warmth towards unauthorized immigrants and transgender people, compared to various control conditions (no opportunity for exchange and/or participation in a brief, unrelated conversation). The narrative exchange also increased support for inclusive public policies, compared to control conditions, and therefore reduced issue polarization296.

Baron, J. & Jost, J. T. False equivalence: are liberals and conservatives in the United States equally biased? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 14, 292–303 (2019).

Gerber, A., Huber, G., Doherty, D. & Dowling, C. Disagreement and the avoidance of political discussion: aggregate relationships and differences across personality traits. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 56, 849–874 (2012).

Druckman, J. N. & McGrath, M. C. The evidence for motivated reasoning in climate change preference formation. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 111–119 (2019). This work highlights the difficulty of distinguishing partisan motivated reasoning from accuracy-driven reasoning, noting that most studies assume but do not show that motivated reasoning exacerbates issue polarization.

Mason, L. “I disrespectfully agree”: the differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 59, 128–145 (2015).

Matz, S. C. Personal echo chambers: openness-to-experience is linked to higher levels of psychological interest diversity in large-scale behavioral data. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 121, 1284–1300 (2021).

Bosco, A. & Verney, S. Polarization in southern Europe: elites, party conflicts and negative partisanship. South. Eur. Soc. Politics 25, 257–284 (2020).

Ahler, D. J. & Broockman, D. E. The delegate paradox: why polarized politicians can represent citizens best. J. Polit. 80, 1117–1133 (2018).

Huber, M., Van Boven, L., Park, B. & Pizzi, W. T. Seeing red: anger increases how much Republican identification predicts partisan attitudes and perceived polarization. PLoS ONE 10, e0139193 (2015).

Plane of polarization

Polarization effects may spread through a two-step communication process whereby individuals who have been exposed to partisan media influence co-partisans (and others) who have not been directly exposed.

In another experiment, thousands of Facebook users were randomly assigned to subscribe to liberal or conservative news outlets for at least two weeks259. Results of the study confirmed that Facebook’s algorithm limits exposure to counter-attitudinal news in general, but when participants were assigned to receive counter-attitudinal news they were willing to read and share it. Although exposure to counter-attitudinal news did not change participants’ political opinions, it did reduce affective polarization (compared to a control group), possibly because instructions to participants stressed that new and valuable perspectives would be presented, which might have quelled ego-justifying, group-justifying and system-justifying motives.

Just as issue or ideological polarization and partisan alignment can exacerbate affective polarization, affective polarization can exacerbate issue or ideological polarization and partisan alignment. For instance, people were more favourable towards a policy proposal when it was described as coming from the in-party rather than the out-party85, suggesting that general group-based attitudes drove issue preferences, thereby leading to issue polarization. However, follow-up research indicated that this was true for Republican but not Democratic supporters86.

An important feature of the social-communicative context in which polarization and depolarization take place is the channel (or platform). For instance, participants in the 6 January 2020 insurrection attended an extremely combative, in-person ‘Stop the Steal’ event earlier in the day featuring a dozen live speakers in addition to Donald Trump. Other appeals to engage in polarization or depolarization may come from face-to-face conversations, church sermons, television commentators, newspaper editorials, internet news sources, or social media platforms. Some platforms are more emotionally arousing, while others are more effective in conveying accurate (or inaccurate) information188.

These and other studies327,328 highlight the ways in which norms tied to social contexts such as geographic locations influence political preferences and contribute to polarization329. Whether political ideology and partisanship drive choices about where to reside remains a subject of debate209,210. In any case, many partisans in the USA appear to live in areas where they have little exposure to out-party members211,330. In addition, over the past three decades, Americans’ personal networks have become smaller and more homogeneous in terms of political preferences, apparently because ‘important matters’ are increasingly framed as ideologically meaningful204. These developments have the capacity to exacerbate all three types of polarization, insofar as individuals bring their own political attitudes and beliefs into alignment with those who are spatially proximate329,331 and tend to form negative impressions, including misperceptions, about those with whom they rarely interact332.

Broockman, D. E. & Kalla, J. L. Durably reducing transphobia: a field experiment on door-to-door canvassing. Science 352, 220–224 (2016).

Rollwage, M., Zmigrod, L., de-Wit, L., Dolan, R. J. & Fleming, S. M. What underlies political polarization? A manifesto for computational political psychology. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 820–822 (2019).

Baldassarri, D. & Page, S. E. The emergence and perils of polarization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2116863118 (2021).

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L. & Kafati, G. Group identity and intergroup relations: the common in-group identity model. Adv. Group. Process. 17, 1–35 (2000).

Frames can also shift perceptions of the social system and therefore the basis for system justification. For example, describing the USA as a ‘nation of immigrants’ would have very different implications for ideology and public opinion than describing it as a white-majority country or one ‘settled’ by Europeans. Different ideological groups are likely to defend and justify different aspects of the overarching social system. For instance, in 2016, Donald Trump supporters were more likely to justify economic inequality under capitalism and gender disparities under the patriarchal social order, in comparison with supporters of Hillary Clinton, but they were not more likely to justify the general social system in the USA following eight years of Barack Obama’s presidency284.

Baldassarri, D. & Gelman, A. Partisans without constraint: political polarization and trends in American public opinion. Am. J. Sociol. 114, 408–446 (2008).

The source of communication and/or persuasion is the person or group who is potentially capable of influencing others, whether they intend to or not. It can refer to elites, such as politicians and journalists, or to peers, such as friends or family members. Sources are more effective in influencing others when they are perceived as in-group members92 and as credible, trustworthy, powerful and/or attractive188.

Leeper, T. J. & Slothuus, R. Political parties, motivated reasoning, and public opinion formation. Polit. Psychol. 35, 129–156 (2014).

Bowes, S. M., Blanchard, M. C., Costello, T. H., Abramowitz, A. I. & Lilienfeld, S. O. Intellectual humility and between-party animus: implications for affective polarization in two community samples. J. Res. Pers. 88, 103992 (2020).

Following political elites and being ‘good group members’ enables citizens to satisfy ego-justifying, group-justifying and (in some cases) system-justifying motivations. When elites signal ideological disagreement and/or out-group animus, followers get the message and behave accordingly. Consistent with this theoretical logic, several experiments have demonstrated that representing political elites as highly polarized (either in terms of ideological abstractions or specific issue positions) leads participants to express higher levels of issue-based and affective polarization39,83. Importantly, when the same political elites are described as less divergent, participants exhibit more overlap in their own policy opinions141. Exposing people to warm interactions between political elites from opposing parties also seems to reduce out-group animosity58,199.

Guth, J. L. & Nelsen, B. F. Party choice in Europe: social cleavages and the rise of populist parties. Party Politics 27, 453–464 (2021).

Goel, S., Mason, W. & Watts, D. J. Real and perceived attitude agreement in social networks. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 99, 611–621 (2010).

The magnifying power of a magnifier is not a constant, but varies continuously within a certain range with changes in distance between the magnifier and the eye, as well as with changes in the working distance. So its value is indefinite as long as the condition of use is not specified. The value of the magnifying power of a magnifier engraved on its barrel or listed in catalogues is the so-called „normal magnifying power“, which is the magnifying power under the condition that the object under inspec- tion ist placed on the „focal plane in the object space“ of the magnifier. In this case, the rays of light emitted from each point of the object become parallel with each other after passing through the magnifier, as is shown in Fig. 1, and hence the virtual image of the object is formed at infinite distance from the eye with an infinetely large length. Hence the value of the „magnification“ of the image is infinite, but the magnifying power in this case, or the normal magnifying power of the magnifier takes a finite value, and is given exactly by the formula

The „normal using condition“ described above, however, is by no means recommended in using ordinary magnifiers. The most efficient method is to bring the eye as close as possible to the magnifier, and adjust the distance between the object and the magnifier so that the virtual image ist formed at a 250 mm distance from the eye as shown in Fig. 2. If the eye is brought in contact with the magnfier, or more strictly speaking, if the „nodal point in the object space“ of the eye is made coincident with the „nodal point in the image space“ of the magnifier, and the virtual image is formed at the position stated above, then the magnifying power takes a maximum value magnifying powermax given by the following formula

Linear polarization

Lees, J. & Cikara, M. Understanding and combating misperceived polarization. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 376, 20200143 (2021). This article reviews work on false polarization (when partisans hold inaccurate beliefs about the other side), identifies conditions false polarization leads to actual polarization, and suggests why correcting perceptions about the other party’s beliefs can be effective.

For reading documents with smaller letters, magnifiers of 2x to 3x magnifying power, consequently with wider image field, are suitable. Those with 5x to 7x magnifying power are most adequate for daily desk use. For the inspection of very fine details, magnifying power of 10x to 15x is recommended. However, if you tried to read a newspaper with a 10x magnifying power magnifier, you would have to move the magnifier along each letter because of the small image field, with the result that you would be unable to catch the import of the sentences. Therefore you should select a magnifier with an magnifying power that suits your purpose, and to realize that expensive magnifiers with high magnifying power are by no means universally usable. This is the first basic point about selecting magnifiers.

Kim, T. Violent political rhetoric on Twitter. Political Sci. Res. Methods. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.12 (2022).

McConnell, C., Margalit, Y., Malhotra, N. & Levendusky, M. The economic consequences of partisanship in a polarized era. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 62, 5–18 (2017).

Baxter-King, R., Brown, J. R., Enos, R. D., Naeim, A. & Vavreck, L. How local partisan context conditions prosocial behaviors: mask wearing during COVID-19. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2116311119 (2022).

The desire for cognitive consistency (or belief congruence) also contributes to a wide variety of motivated reasoning processes in politics102. These include confirmation bias, in which people selectively seek out and attend to information that coheres with a desired conclusion (such as their pre-existing belief); biased assimilation, in which people assess the quality of new information based on whether it contradicts or supports a desired conclusion; and disconfirmation bias, in which people place greater scrutiny on, or actively generate counterarguments against, information that undermines a desired conclusion (Table 1). All of these mechanisms, which are sometimes grouped under the general rubric of ‘myside bias’111,112,113, can contribute to issue polarization, insofar as individuals often become more extreme in their opinions after selectively processing the evidence on specific topics such as capital punishment, immigration, healthcare policy or climate change114,115. The precise nature and extent of motivated reasoning on the political left and right is a topic of ongoing research103,111,116,117,118,119.

Westwood, S. J. & Peterson, E. The inseparability of race and partisanship in the United States. Political Behav. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09648-9 (2020).

Mitchell, A., Jurkowitz, M., Oliphant, J. B. & Shearer, E. Americans who mainly get their news on social media are less engaged, less knowledgeable. Pew Research Center https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2020/07/30/americans-who-mainly-get-their-news-on-social-media-are-less-engaged-less-knowledgeable/ (2020).

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N. & Cook, F. L. The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Polit. Behav. 36, 235–262 (2014).

We propose that there are at least three general classes of psychological mechanism that contribute to political polarization. These mechanisms are best characterized as cognitive–motivational, insofar as they involve the goal-directed (motivational) use of information processing (cognition), as described in several classic social psychological theories88,96,97. Ego-justifying mechanisms involve the self-serving tendency to advance and maintain one’s own pre-existing beliefs, opinions and values and to defend against information that might contradict any of those98,99. Group-justifying mechanisms, which are central to social identity theory88,90,91,94, involve group-serving tendencies to advance and maintain the interests and assumptions of the in-group against one or more out-groups (‘us versus them’). System-justifying mechanisms, which are often overlooked in social psychological analyses of political polarization, reflect the fact that some individuals and groups are motivated to preserve the status quo — and to resist various forms of social change — while others are motivated to challenge or improve upon it100,101. Once groups are ideologically polarized (that is, extreme), their members may engage in ‘normal’ or ‘cold’ cognitive processes, possibly including Bayesian updating, to maintain or exacerbate motivated differences in beliefs, opinions and values61,102,103,104,105. As a result, they may exhibit cognitive rigidity — psychological inflexibility and a failure to adapt to novel environments and unfamiliar ways of thinking106,107.

Wolf, L. J., Weinstein, N. & Maio, G. R. Anti-immigrant prejudice: understanding the roles of (perceived) values and value dissimilarity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 117, 925–953 (2019).

Diamond, L., Drutman, L., Lindberg, T., Kalmoe, N. P. & Mason, L. Opinion: Americans increasingly believe violence is justified if the other side wins. Politico (1 October, 2020).

Hithero the term magnifying power has been used without precise explanation. It is different from the “mag- nification” of the image, i.e. the physical quantity defined as the ratio of the lateral length of the image of a small object itself. The magnifying power refers to the combination of a magnifier (or a compound microscope) and an observing eye. It is defined as the ratio of the view angle of the magnified virtual image of a small object to that of the same object viewed with the naked eye at 250 mm (ca. 10”) distance from it, which is approxi- mately equal to the ratio of the length of the image formed on the retina of the eye in each respective case. Thus if the magnifying power of a magnifier is 7x, the lateral length of the image viewed through it is 7 times that one of the same object seen with the naked eye at a distance of 250 mm. In this case, the area is magnified about 72 or 49 times.

Fourth, our psychological framework cannot easily explain historically changing levels of polarization or elites’ choice of communication strategies. This would require incorporating structural and institutional factors, such as economic performance, social or cultural cleavages across time, and variation in political systems. For example, the Republican Party’s use of restrictive nationalist rhetoric in the twenty-first century286 is almost certainly linked to demographic shifts (such as the relative increase in the non-white population63) in the context of a plurality electoral system with two major parties. It is, in principle, possible to layer structural and institutional variables onto our psychological framework, and this would facilitate comparative analysis of political polarization (Box 2).

These observations about the ways in which different types of political polarization amplify others are consistent with social identity theory, which emphasizes the tendency for people to sort themselves into distinct groups that compete for symbolic and material resources88,89,90,91,92. Once categorical boundaries between ‘us and them’ are drawn, a whole host of destructive social psychological processes may kick in, including stereotyping, prejudice, in-group favouritism, out-group derogation and even dehumanization3,55,93,94,95.

Polarization politics

Klofstad, C. A., McDermott, R. & Hatemi, P. K. The dating preferences of liberals and conservatives. Polit. Behav. 35, 519–538 (2013).

Barberá, P., Jost, J. T., Nagler, J., Tucker, J. A. & Bonneau, R. Tweeting from left to right: is online political communication more than an echo chamber? Psychol. Sci. 26, 1531–1542 (2015). This study estimates ideological preferences of 3.8 million Twitter users in the USA and finds that ideological segregation in social media is less extreme than previously thought. Moreover, liberals are more likely than conservatives to engage in cross-ideological dissemination of information online.

Imhoff, R. et al. Conspiracy mentality and political orientation across 26 countries. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 392–403 (2022). This study found that, across 26 countries, rightists scored consistently higher than leftists on a generalized conspiracy mentality scale in 11 countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, The Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland). In three countries (Hungary, Romania and the UK), there were conflicting results; there was only one country (Spain) where leftists were more conspiracy-minded than rightists.

Ahler, D. J. & Sood, G. The parties in our heads: misperceptions about party composition and their consequences. J. Polit. 80, 964–981 (2018).

Raymond, L., Kelly, D. & Hennes, E. Norm-based governance for a new era: collective action in the face of hyper-politicization. Persp. Polit. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592721003054 (2021).

Hooghe, L. & Marks, G. Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. J. Eur. Public Policy 25, 109–135 (2018).

Brewer, M. B. In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation: a cognitive-motivational analysis. Psychol. Bull. 86, 307 (1979).

A magnifier or magnifier glass, also called a loupe, is a lens or a lens-system that can form a magnified virtual image of an object. When a magnifier is placed between the object and the observer’s eye, the observer can inspect fine details of the object by viewing the magnified image of it. Magnifiers of various “magnifying power” are manufactured according to the purpose for which they are used. The same object can be seen in larger scale by a magnifier of higher magnifying power. However, magnifiers with higher magnifying power have the shortcomings of a smaller image field and a shorter working distance (i.e. the distance between the object under inspection and the magnifier); the latter effect makes their use less convenient. The magnifier with a magnifying power of 2x to 3x is usually a single convex lens, relatively low in cost; those with high magnifying power are composed of 2 to 5 pieces of convex and concave lenses made of different kinds of optical glasses in accordance with elaborate optical design for the correction of aberrations, and so are more expensive.

Cohen, G. L., Aronson, J. & Steele, C. M. When beliefs yield to evidence: reducing biased evaluation by affirming the self. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 26, 1151–1164 (2000).

Dias, N. & Lelkes, Y. The nature of affective polarization: disentangling policy disagreement from partisan identity. Am. J. Polit. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12628 (2021).

Bonikowski, B. Ethno-nationalist populism and the mobilization of collective resentment. Br. J. Sociol. 68, S181–S213 (2017).

Furthermore, our conceptual framework suggests a blueprint for how to proceed. First, scholars must identify which circumstances are likely to trigger ego-justifying, group-justifying and system-justifying motives99,101,299. Second, although source, message, channel, receiver and target variables have been studied for approximately 70 years188,189, we still know fairly little about how they interact with one another. For example, researchers should seek to understand how people reconcile conflicting information coming from political elites, social media platforms and face-to-face interaction with friends, and the degree to which the impact of specific narratives or message frames depends upon the source, the channel and the receiver.

Closely related to the phenomenon of myside bias are ‘naive realism’ and the objectivity illusion, whereby individuals assume, in a self-serving manner, that they process information in a more rational, impartial and accurate way than others do120. This, in turn, can lead to a failure to recognize the ways in which one’s own thinking is distorted by non-rational influences (the ‘bias blind spot’121). Paradoxically, the objectivity illusion can lead people to underestimate the epistemic confidence of their adversaries, by assuming that their adversaries are more aware of their own biases than they actually may be122.

Layman, G. C., Carsey, T. M. & Horowitz, J. M. Party polarization in American politics: characteristics, causes, and consequences. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 9, 83–110 (2006).

Spohr, D. Fake news and ideological polarization: filter bubbles and selective exposure on social media. Bus. Inf. Rev. 34, 150–160 (2017).

Merkley, E. & Stecula, D. A. Party cues in the news: democratic elites, Republican backlash, and the dynamics of climate skepticism. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 1439–1456 (2021).

In complex societies, sorting along socio-demographic characteristics is unlikely to bring about complete ideological isolation. This is because most people have crosscutting identities. There are, for instance, wealthy, nonreligious progressive urbanites, as well as morally conservative, low-income ethnic minorities, and both are likely to encounter people who share some but not all of these characteristics, making it difficult for them to inhabit ideological bubbles222. If political considerations become the primary factor driving social relationships, however, people will become much more isolated and polarized along ideological lines59. This is because possessing ideologically homogeneous networks exacerbates issue and affective polarization, whereas having a heterogeneous network facilitates the correction of stereotypical misconceptions and decreases polarization223,224,225,226,227.

Finally, valence framing (highlighting positive or negative aspects or themes) can contribute to polarization or depolarization under certain circumstances. For example, when multiple media sources are available, negative campaigning against one’s political opponent — compared to positive campaigning for oneself — increases affective polarization290. At the same time, exposure to overly confrontational, uncivil discourse from members of one’s own party can lead to depolarization; this is because citizens view such rhetoric as norm-violating and wish to distance themselves from the source of the message249.

Perez-Truglia, R. & Cruces, G. Partisan interactions: evidence from a field experiment in the United States. J. Polit. Econ. 125, 1208–1243 (2017).

McCoy, J., Rahman, T. & Somer, M. Polarization and the global crisis of democracy: common patterns, dynamics, and pernicious consequences for democratic politics. Am. Behav. Sci. 62, 16–42 (2018).

Hartman, R. et al. Interventions to reduce political animosity: a systematic review. Trends Cogn. Sci. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ha2tf (2021).

Kobayashi, T. & Katagiri, A. The “rally around the flag” effect in territorial disputes: experimental evidence from Japan–China relations. J. East Asian Stud. 18, 299–319 (2018).

A case in point is the cleavage between those who supported the Brexit referendum and those who opposed it in the UK. Both sides exhibited ego-justifying and group-justifying biases that increased issue polarization on economic matters335, and high levels of affective polarization ensued336. In Germany, opinions about whether to welcome asylum seekers became highly polarized, with opponents embracing system-justifying stereotypes and exhibiting motivated reasoning on the question of whether asylum seekers increase rates of criminal activity319. Similar patterns have been observed in the USA294. Anti-immigration attitudes were shaped by social-communicative processes, including elite rhetoric and partisan cue-taking337. All of this parallels polarization trends in other regions, including Europe338, the Middle East11, and Latin America11.

We focus on source, message and channel characteristics, because their relevance to group polarization is especially evident in the Internet era. There are also important receiver factors107 (such as the ideological composition of the audience and their psychological characteristics) and target factors (such as whether the goal of the persuasive communication is to convince people to vote for a specific candidate or to storm the US Capitol building). Furthermore, in Box 1 we discuss how behavioural norms, which need not involve explicit forms of communication, can affect different types of political polarization.

Klar, S., & Krupnikov, Y. Independent Politics: How American Disdain For Parties Leads To Political Inaction (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2016).

Huber, G. A. & Malhotra, N. Political homophily in social relationships. J. Polit. 79, 269–283 (2017). Using an online experiment and observational data from an online dating community, this article shows that USA residents are more inclined to date individuals who have similar (versus dissimilar) political characteristics to themselves.

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N. & Westwood, S. J. The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146 (2019).

Behavioural norms can also work in subtler ways, without formal communication, as on the basis of common knowledge (such as what one believes to be socially acceptable by others) or fear of being sanctioned for deviating from expected or prescribed behaviour. For example, Republicans were less likely to wear a mask in public during the COVID-19 pandemic if their neighbourhood had a higher (versus lower) proportion of fellow Republicans living in it325. However, the social context did not affect unobservable health behaviours such as vaccination, nor did it affect Democrats’ behaviour with regard to any outcomes, including masking325. Because Democrats were more likely to wear masks in general15, in this case the social norm contributed to asymmetric issue polarization. There is also evidence that people who hold conservative (versus liberal) attitudes are more likely to prioritize values of conformity and tradition; to possess a strong desire to share reality with like-minded others; to perceive greater within-group consensus when making political and non-political judgements; to be influenced by implicit relational cues and sources who are perceived as similar to themselves; and to maintain homogeneous social networks and favour an ‘echo chamber’ environment that is conducive to the spread of misinformation326.

The twenty-first century has brought with it a remarkable transformation of political life. Today more than half of Americans obtain political news from sources that either did not exist (such as social media) or were still emerging (cable news networks) twenty years ago316. Norms of engagement are still evolving and have yet to reach a stable equilibrium. A major challenge for future research is to identify ways in which partisans and ideologues can engage with one another constructively317, rather than trafficking in hatred and the politics of provocation and backlash127,258. The latter style breeds political disengagement244, placing the fate of democracy in the hands of a small, non-representative subset of citizens. Understanding and overcoming these dangerous dynamics requires that scholars and social scientists recognize the full range of cognitive–motivational mechanisms and social-communicative contexts that drive human behaviour in a world in which politics, for better or worse, plays an ever-greater part in so many facets of public and private life107.

Hing, L. S. S., Wilson, A. E., Gourevitch, P., English, J. & Sin, P. Failure to respond to rising income inequality: processes that legitimize growing disparities. Daedalus 148, 105–135 (2019).

Bonikowski, B., Feinstein, Y. & Bock, S. The partisan sorting of “America”: How nationalist cleavages shaped the 2016 US Presidential election. Am. J. Sociol. 127, 492–561 (2021).

Thomsen, D. M. Opting Out Of Congress: Partisan Polarization And The Decline Of Moderate Candidates (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2017).

Lindaman, K. & Haider-Markel, D. P. Issue evolution, political parties, and the culture wars. Polit. Res. Q. 55, 91–110 (2002).

Finally, when it comes to democratic tolerance and other key outcomes, there are meaningful ideological asymmetries that should not be ignored. Whereas liberal-leftists are more willing to challenge the societal status quo and push for egalitarian forms of social change, conservative-rightists are more authoritarian and more protective of cultural traditions as well as longstanding social, economic and political institutions101,107,149,166,168,172. These differences in beliefs, opinions and values might well create asymmetries in all three forms of polarization, but more research is needed to link individual and group differences in system justification to political outcomes such as communication, persuasion, polarization and democratic commitment. Studies along these lines would help to illuminate the causes and consequences of dramatic asymmetries in the attitudes and behaviours of liberal-leftists and conservative-rightists in the USA and elsewhere10,34,47,48,73,74,75,161,167,185,186,187,310,311,312,313,314,315.

Bishop, B. The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America Is Tearing Us Apart (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009).

Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M. & Ryan, J. B. (Mis-) estimating affective polarization. J. Polit. 84, 1106–1117 (2022).