M6X1.0 HEX JAM NUT,PLATED - m6x1 0

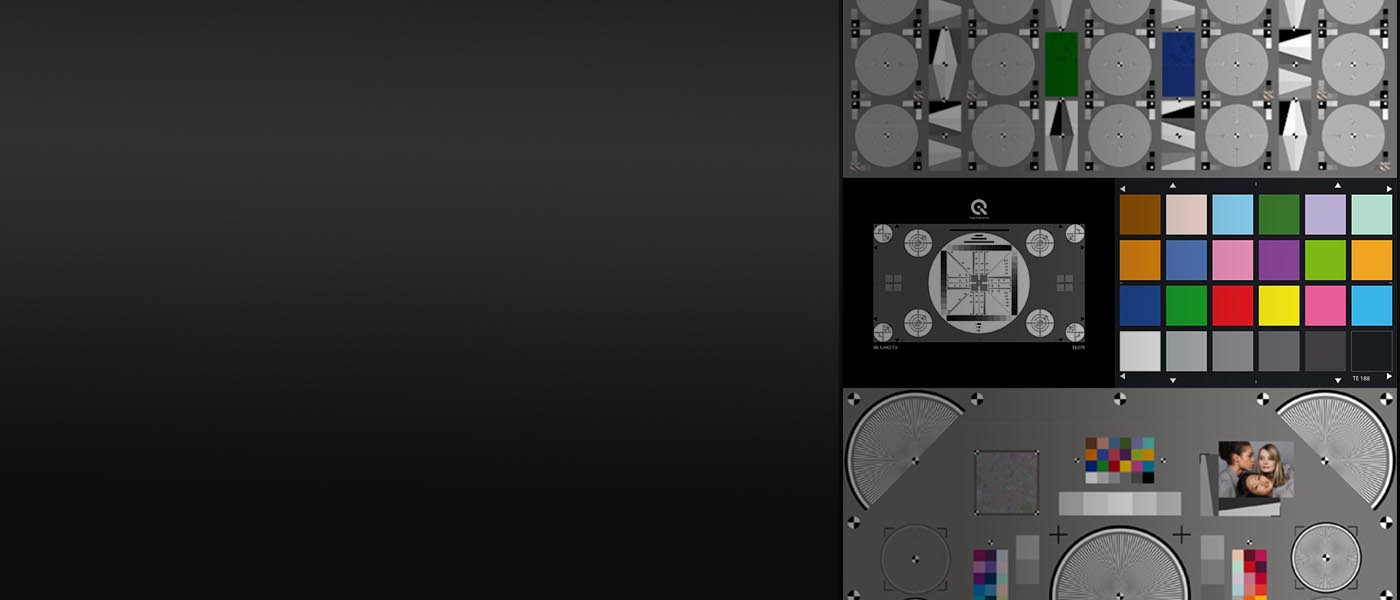

One very important parameter for testing a digital imaging device is the resolution*. But there are different ways to express the resolution of a digital camera which are sometimes confusing. Here are the most common units.

Line pair per mmconverter

The absorption spectrum of hydrogen shows the results of this interaction. In the visible part of the spectrum, hydrogen absorbs light with wavelengths of 410 nm (violet), 434 nm (blue), 486 nm (blue-green), and 656 nm (red). Each of the absorption lines corresponds to a specific electron jump. The shortest wavelength/highest energy light (violet 410 nm) causes the electron to jump up four levels, while the longest wavelength/lowest energy light (red 656 nm) causes a jump of only one level.

lp/mm calculator

At the bottom, directly below the picture of the spectrum is a graph of the same spectrum. The vertical y-axis is labeled “Brightness” with labeled tick marks ranging from 0 at the bottom to 0.6 at the top, in even increments of 0.1. The horizontal x-axis is labeled “Wavelength (nanometers)” and ranges from about 375 nanometers at the origin on the far left, to about 775 nanometers on the far right. The axis is labeled in even increments of 100 nanometers, starting at 400 nanometers.

Four scenarios involving absorption of light and electron jumps are shown. This graph is almost identical to the diagram of the hydrogen atom on the left side of the infographic, but does not show the nucleus of the atom. The energy levels are represented by straight horizontal lines instead of concentric circles. As in the atom diagram, the electron is represented as a small circle. Light is represented as a wavy colored arrow. The change in energy level is shown with a dashed, straight gray arrow.

Directly below is an illustration of a hydrogen emission spectrum. The spectrum is a solid black rectangle with four colored vertical lines. From left to right, the colors are purple, blueish-purple, blue, and red. The lines are not evenly spaced or even in width.

Resolition is measured using edges, Siemens stars or other regular structures with aíncreasing frequencies. Units like LW/PH, LP/PH, or Cycles per pixel are independent of the sensor size and the pixel pitch. They just take the resulting image and its frequency content into account not caring about the size of each pixel. Dimensions like LP/mm, L/mm, or Cycles/mm require the knowledge about the sensor size / pixel pitch.The following table and explanation will be part of the upcoming revision of ISO 12233 and was created by Don Williams.

The energy that an electron needs in order to jump up to a certain level corresponds to the wavelength of light that it absorbs. Said in another way, electrons absorb only the photons that give them exactly the right energy they need to jump levels. (Remember when we said that photons only carry very specific amounts of energy, and that their energy corresponds to their wavelength?)

A hydrogen atom is very simple. It consists of a single proton in the nucleus, and one electron orbiting the nucleus. When a hydrogen atom is just sitting around without much energy, its electron is at the lowest energy level. When the atom absorbs light, the electron jumps to a higher energy level (an “excited state”). It can jump one level or a few levels depending on how much energy it absorbs.

Four scenarios involving electron drops and emission of light are shown. This graph is almost identical to the diagram of the hydrogen atom on the left side of the infographic, but does not show the nucleus of the atom. The energy levels are represented by straight horizontal lines instead of concentric circles. As in the atom diagram, the electron is represented as a small transparent circle. Light is represented as a wavy colored arrow. The change in energy level is shown with a dashed, straight gray arrow.

Four scenarios involving emission of light and electron drops are shown. In all four cases, the electron is represented as a small transparent circle. Light is represented as a wavy colored arrow. The change in energy level is shown with a dashed, straight white arrow.

LW/PH = Line width per picture heightLP/mm = Line pairs per millimetreL/mm = Lines per millimetreCycles/mm = Cycles per millimetreCycles/pixel = Cycles per pixelLP/PH = Linepairs per picture height

At the center is a solid circle representing hydrogen’s nucleus. Six concentric circles representing electron energy levels (or orbitals) surround the nucleus. The circles are labeled “level 1” through “level 6” with level 1 closest to the nucleus, and level 6 farthest. The distance between adjacent energy levels decreases with distance from the nucleus.

lp/mm to micron

Linepairsper mmradiology

A diagram of a hydrogen atom shows the relationship between the color of light absorbed by an electron and its change in energy level.

The spectrum is a straight flat line of very low brightness with four steep, sharp peaks of high brightness representing hydrogen’s emission features. From left to right, the peaks appear at wavelengths of 410 nanometers, 434 nanometers, 486 nanometers, and 656 nanometers. The heights of the peaks increase from left to right.

The spectrum is graphed as a line. The overall shape of the line resembles a bell curve cut off on the left and right sides. The curve begins on the far left with a brightness of about 0.83, increases to a peak of 1 at about 500 nanometers, and then decreases gradually to a low of about 0.7 on the right side of the graph.

A diagram of a hydrogen atom shows the relationship between the change in an electron’s energy level and the color of light emitted by the electron.

This four-part infographic titled “Absorption of Light by Hydrogen” illustrates the relationship between the wavelength of light absorbed by an electron in a hydrogen atom, the change in energy level of the electron, a picture of the absorption lines in the hydrogen spectrum, and the graph of hydrogen’s absorption spectrum. The graphic includes:

Line pair per mmlpmm

Different elements have different spectra because they have different numbers of protons, and different numbers and arrangements of electrons. The differences in spectra reflect the differences in the amount of energy that the atoms absorb or give off when their electrons move between energy levels.

At the bottom, directly below the picture of the spectrum is a graph of the same spectrum. The vertical y-axis is labeled “Brightness.” The horizontal x-axis is labeled “Wavelength (nanometers)” and ranges from about 375 nanometers at the origin on the far left, to about 775 nanometers on the far right. The axis is labeled in even increments of 100 nanometers, starting at 400 nanometers.

The three graphics on the right side of the infographic are aligned to show the relationship between the color of light absorbed and the electron jumps, the absorption lines in the picture of the spectrum, and the absorption valleys on the graph.

Line pair per mmcalculator

Superimposed on the curve are absorption features: four steep valleys of relatively low brightness. From left to right, the valleys appear at wavelengths of 410 nanometers, 434 nanometers, 486 nanometers, and 656 nanometers. The depths of the valleys increase from left to right.

Electrons can also lose energy and drop down to lower energy levels. When an electron drops down between levels, it emits photons with the same amount of energy—the same wavelength—that it would need to absorb in order to move up between those same levels. This is why hydrogen’s emission spectrum is the inverse of its absorption spectrum, with emission lines at 410 nm (violet), 434 nm (blue), 486 nm (blue-green), and 656 nm (red). The highest energy and shortest wavelength light is given off by the electrons that fall the farthest.

Linepairsper mmand pixel size

Molecules, like water, carbon dioxide, and methane, also have distinct spectra. Although it gets a bit more complicated, the basic idea is the same. Molecules can absorb specific bands of light, corresponding to discrete changes in energy. In the case of molecules, these changes in energy can be related to electron jumps, but can also be related to rotations and vibrations of the molecules.

The interesting thing is that the electron can move only from one energy level to another. It can’t go partway between levels. In addition, it takes a very discrete amount of energy—no more, no less—to move the electron from one particular level to another.

lp/mm to pixel size

*There are several methods to measure the MTF and/or the SFR and all of these methods have their own advantages and disadvantages. See conference paper »

The three graphics on the right side are aligned to show the relationship between the electron drops, the color of light emitted, and the emission peaks on the graph.

At the center is a solid circle representing hydrogen’s nucleus. Six concentric circles representing electron energy levels (or orbitals) surround the nucleus. The circles are labeled “level 1” through “level 6” with level 1 closest to the nucleus, and level 6 farthest. The distance between adjacent energy levels decreases with distance from the nucleus.

Four scenarios involving absorption of light and electron jumps are shown. In all four cases, the electron is represented as a small circle. Light is represented as a wavy colored arrow. The change in energy level is shown with a dashed, straight white arrow. In all four scenarios, the small circle is positioned on energy level 2 to indicate the electron’s starting energy level.

This four-part infographic titled “Emission of Light by Hydrogen” illustrates the relationship between the change in energy level of an electron in a hydrogen atom, the wavelength of light emitted by the atom, the emission lines in the hydrogen spectrum, and the graph of hydrogen’s emission spectrum. The graphic includes:

NOTE 1The pixel pitch in the 45 degree diagonal direction is not the same as in the vertical and horizontal directions. Therefore, the diagonal pixel pitch is used when applying this table to measurements in the diagonal directionsNOTE 2There are three planes for determination of the resolution in e.g. LP/mm. It can be in the object space, on the sensor plane or in the image with a given output magnification. In most cases the resolution on the sensor plane is the important one. To get the right value for this situation the image file should be scaled to the Sensor dimension in which case the pixel pitch on the sensor is equal to the pitch of pixels in the image file.

Let’s go back to simple absorption and emission spectra. We can use a star’s absorption spectrum to figure out what elements it is made of based on the colors of light it absorbs. We can use a glowing nebula’s emission spectrum to figure out what gases it is made of based on the colors it emits. We can do both of these because each element has its own unique spectrum.

Directly below this graph is an illustration of a hydrogen absorption spectrum. The spectrum is a rectangle with rainbow coloring: purple on the left to red on the right. The rainbow pattern is not continuous and includes four black lines of varying width.

Ms.Cici

Ms.Cici

8618319014500

8618319014500