Depth of Field and Depth of Focus - depth of filed

You have three options for decreasing your depth of field. You can widen your aperture by decreasing the f/stop number, moving closer to your subject, or using a longer focal length.

It’s possible to simulate a shallow depth-of-field effect digitally. You can add a blur effect in Photoshop or use apps or editing software that digitally simulate the effect.

The top highlights DoF when using an aperture of f/2.8. The girl is in focus, but the dog in the foreground and the tree in the background are blurry.

Using the wide aperture f/4 kept Depth of Field very shallow to capture the mushrooms in focus with a blurry background. DOF was also made shallower by shooting extremely close to the subject. Olympus E-M5 III, Olympus 12-40mm f/2.8 lens.

While the other types of image degradation happen at wide apertures, diffraction causes the image to be unsharp at small aperture. It makes the picture look slightly blurry or out of focus. Landscape photographers tend toward using small apertures for maximum DOF, but the gain in sharpness is counteracted by diffraction. It happens when light squeezes through the narrow opening of a small aperture, causing it to bend and form a distorted image. The opening of small apertures like f/16 or f/22 is a mere pinhole.

A landscape photographer may take three or more images. The first focuses on the foreground element, the second on the midground, and the third on the background.

When you select a focal point, the focus isn’t equally distributed in front of and behind this point. Most of the time, one-third of your focus falls in front of your focal point and the other two-thirds behind it.

On Full-frame cameras, minor diffraction becomes noticeable above f/11. Many landscape photographers automatically use f/16, unaware that diffraction might affect resolution. This was standard practice in the film days because film lacked enough resolution to actually show the effects of diffraction. However, small f/stops should only be used when necessary. When using a wide-angle lens, f/11 has sufficient DOF for most landscapes. f/16 should be reserved for scenes with close foreground objects.

Diffraction is more severe on cropped formats because the f/stop diameters are even smaller than the same f/stops on full-frame lenses. This applies to APS-C, Micro Four Thirds (MFT) and compact cameras. Diffraction generally worsens by the format’s crop factor when compared to full-frame. For example, MFT has a crop factor of 2x, so diffraction at f/11 is roughly as severe as a full-frame lens at f/22. Diffraction is a particularly important consideration for MFT and smaller formats because it becomes noticeable at much wider f/stops than full-frame. On MFT, diffraction becomes noticeable above f/8.

Finally, the focal length of your lens also impacts the DoF. If you have a zoom lens, try a with less zoom for a greater depth of field. Changing the focal length also affects your composition. So, balancing the perfect DoF with the perfect frame is best.

This is one reason portrait photographers prefer apertures of f/1.4 to f/5.6. It’s also why landscape photographers prefer apertures from f/11 to f/22. But that’s not all there is to it. Other details factor into how wide or narrow your depth of field is.

DOF isn’t controlled entirely by the aperture. DOF becomes shallower by moving closer to the subject. If you get very close to the subject, it’s possible to have a blurry background even when using a small aperture. Also, the higher the lens focal length, the shallower the DOF at each f/stop.Using the small aperture f/16 created broad Depth of Field so you can see the village in the background. Olympus E-M5 III, Olympus 12-100mm f/4 lens.

The aperture setting is the easiest way to control DoF. Generally speaking, the wider the aperture, the shallower the depth of field. But opening up the aperture lets in more light. You may need to balance the increased light with a faster shutter speed.

Fast lenses are significantly more expensive and bigger because they’re constructed of larger, more complex glass elements. For example, Sony offers a 16-35mm lens in an f/4 version that costs around $1000, and a f/2.8 version for over $2000.

Notice that the DoF in front and behind my subject changes a lot. With an aperture of f/11, my DoF was 9.32 ft (2.84 m). With f/2.8, only 1.97 ft (0.6 m) will be in focus. It’s a much narrower range.

You should use the sweet spot whenever possible. This would most typically be in compositions where DOF doesn’t matter, like when all of the elements fall within the same plane of focus. An example is a picture of a distant mountain with nothing in the near foreground. In this case, DOF would look the same whether you shot it at f/2.8 or f/16 because the mountain falls within a single plane of focus.

The aperture isn’t the only mechanism that regulates light. Shutter Speed, ISO* and ambient light also do. Light can flow through each by any proportion, but it must add up to 100% for proper exposure. Whenever light is changed by opening or closing the aperture, an equal amount of light must be added or subtracted by changing the shutter speed, ISO, or literally by adding light to the scene. Shutter speed and ISO are also adjusted in stops. Slowing the shutter speed from 1/500th sec to 1/250th sec increases light by 1 stop. Changing ISO from 800 to 400 removes a stop. If the sun emerges from behind the clouds, this may add several stops of light to the scene and you have to adjust the settings accordingly. This interconnected relationship between aperture, shutter speed and ISO is called the exposure triangle.

Landscape photographers often want the entire scene in focus, from the closest rock to the farthest mountain. This is a “deep” depth of field. In the landscape image below, there is a deep DoF. The waterfall in the background and the trees and rocks in the foreground are in focus.

f-number

But there’s a bit more to it than that. A 200mm lens focused at 9.8 ft (3 m) doesn’t show you the same composition as a 50mm lens focused at the same distance.

Vignetting is when the corners of the frame appear darkened. It’s most visible at a lens’ maximum aperture. At wide apertures, light enters the lens from various angles. Light from diagonal angles reaches the center of the camera’s sensor, but it’s physically blocked by the lens barrel from directly reaching the corners. This results in light fall-off in the corner of the image. Vignetting disappears as the f/stop approaches the lens’ sweet spot. It’s easily corrected in post-processing or can be left as a deliberate creative effect.

LoCA appears as red, green, yellow or bluish colored fringing along the lines and details in an image. The fringing can bleed across the image, causing it to look blurred. When present, it’s more noticeable at wide f/stops. It’s caused when the lens focuses different wavelengths of color at slightly different positions on the focal plane. LoCa is usually a minor problem that isn’t obvious on all lenses. It can be reduced by using a smaller f/stop. Fringing in the final image can be reduced in post-processing. There are several types of chromatic aberration, but LoCa is the one affected by aperture.

If you want to take advantage of a narrow depth of field, you need distance between the subject and background. For instance, if your model stands against a wall, you can’t blur the wall. The model and the wall are on the same plane of focus. So, ask your model to step towards you.

With flowers in the foreground and mountains behind it, this scene demanded a lot of DOF. f/11 handled it just fine. Nikon D810, Nikon 16-35mm f2.8 lens.

There is one instance where your DoF can be manipulated. That is by using a tilt-shift lens. By playing around with the “tilt” of a lens, you can place an entire scene in focus when using a wide aperture.

Spherical aberration causes softness in the image center when shooting at wide f/stops. It happens because light rays passing through the edge of the lens don’t converge at exactly the same point as rays passing through the center of the lens. You can minimize it by shooting at a smaller f/stop. It’s probably worth tolerating a bit of softness from aberration if you’re after the shallowest possible DOF. Some lenses are so good that softness from aberration is barely present when shooting at wide apertures.

Pupilaperture

To become familiar with the f/stops, set your camera to Aperture Priority mode and remove the lens cap. Find the f/ number on the display-it may look something like this: “F 11”. Rotate the aperture dial and observe how the f/ number changes as you cycle through them. Also observe how the shutter speed changes as you change the f/stop. The 1/3 stops in between the prime f/stops are just for fine tuning-you don’t need to pay too much attention to them.

The portrait below has a shallow depth of field. Notice the near eye (left) is in focus, but the back eye (right) is blurred. To get both eyes and nose in focus, you would need to use a narrower aperture (larger f-number).

*ISO doesn’t physically transmit any light to the sensor. It’s digital gain, which means that it artificially adds exposure to the image.

I enter my camera body (Sony a7R IV) and 50mm lens. But this time, I’ll put f/2.8 instead of f/11. To be consistent, I’ll keep my subject’s distance at 9.84 ft (3 m).

To do this, you use a shallow depth of field, meaning your foreground is in focus, but the background is not. This is also called bokeh.

Changing the depth of field in photography is a great technique all photographers should know. To increase your depth of field, you have three options. You can narrow your aperture by increasing the f-stop number, moving further away from your subject, or using a shorter focal length.

Shallow Depth of Field can create a dreamy effect with only the subject sharp and everything else blurry. DOF was also made shallower in this shot because I used a telephoto lens. I shot this at the lens’ widest aperture of f/4. I also left the corner vignetting intact because it looks cool, an artifact of shooting wide open. Sony A7rV, Sony 100-400mm G Master f/4 lens.

Choosing the right depth of field affects all types of photography, from portraits to landscapes. Continue reading to understand depth of field and how to use it in your photos.

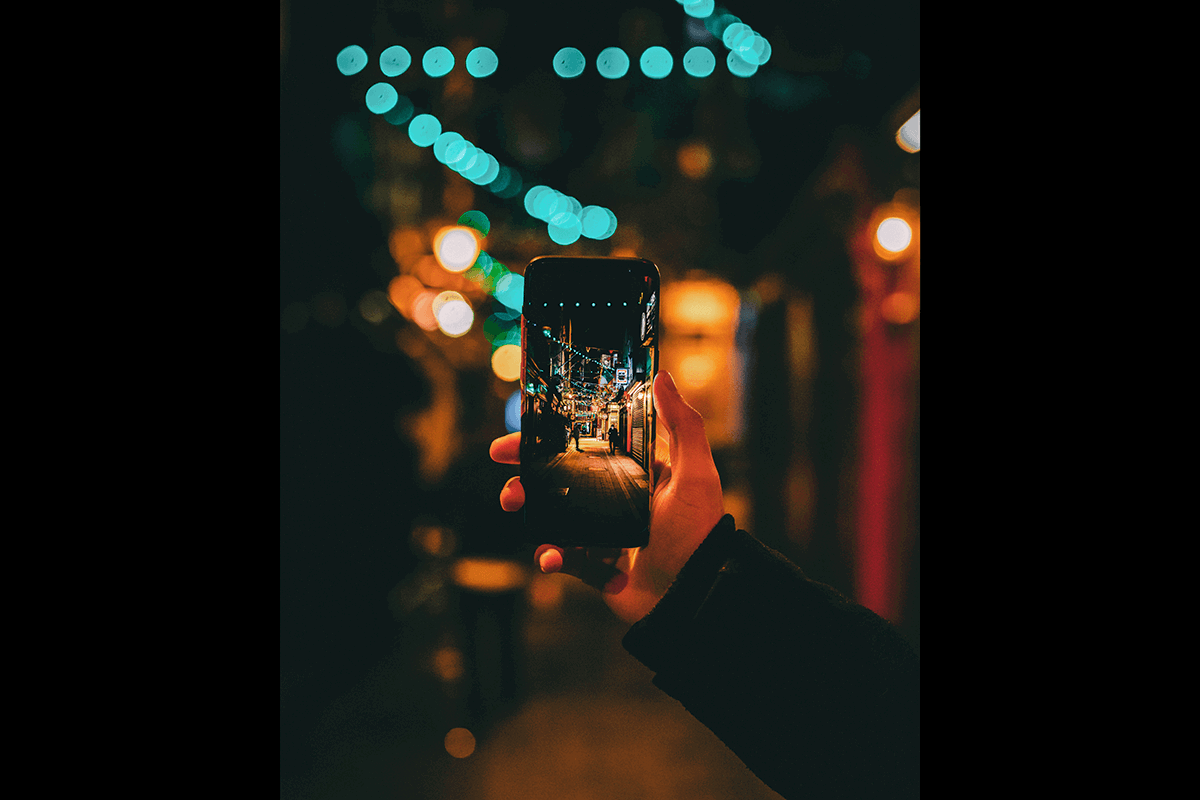

It is possible to combine a shallow and deep depth of field in one photo. The photo below cleverly uses a smartphone to capture a wide DoF in the image. Then, they photographed the image on the phone using a shallow depth of field.

Now that I’ve introduced you to the DoF calculator, play with it a bit. Enter your camera body and focal lengths to see how the numbers change. Many factors control the depth of field.

Depth of field in photography describes how much of the scene is in focus. More specifically, DoF is the distance between the closest and farthest points of the image that are in focus.

F-stop

In photography jargon, a fast lens has a large maximum aperture like f/2.8 or wider. A slow lens has a smaller maximum aperture like f/5.6. Fast implies that the lens transmits more light, allowing a faster shutter speed to freeze movement. A fast lens also has shallower depth of field at the maximum aperture, making it easier to create images with a blurred background.

Remember, it’s extremely difficult to create a blurred background if your subject and the background are too close. Creating the depth of field you want is all about depth relationships.

Depth of field has much to do with distance—but relative distance rather than absolute distance. Moving farther away from your subject gives a greater DoF. In contrast, moving closer gives a shallower DoF.

First, I enter my camera (Sony a7R IV—because sensor size affects DoF. Then, I enter the focal length of my lens, which is a 50mm lens set at f/11. Lastly, I put in how far away I am from my subject, about 9.84 ft (3 m).

Our eyes are drawn to the in-focus area of a photo. So, as a general rule, you should focus on the point of greatest interest. Depth of field tells you how much of the scene is in focus in front of your focal point. It also tells you how much of the background is in focus.

The depth of the field isn’t affected by just one setting on your camera. As we’ve shown, you can change three variables to affect the depth of the field. These are aperture, focal length, and relative distance.

The main reason you open or close the Aperture is to affect Depth of Field. DOF is how much of the photo is in focus on either side of the plane that you’ve focused on. A wide aperture like f/2.8 produces shallow DOF, and a small one like f/16 creates greater DOF. In a photo with shallow DOF where the subject is sharp and the background is blurred, a wide aperture like f/2.8 or f/4 was used. In landscape photography, a small aperture like f/11 or f/16 creates enough DOF to capture most of the scene from front to back in focus.

I’ll finish our article by introducing you to some topics related to depth of field. Focus stacking is a way of creating a very deep DoF. It is also possible to simulate a shallow depth of field. This is particularly useful when using a smartphone.

The aperture is arguably the most important setting on your camera because it has the strongest impact on the aesthetic of photos. It affects 2 things; depth of field and the amount of light reaching the sensor. The aperture is a mechanical diaphragm inside the lens that can be opened and closed to create a larger or smaller hole. The specific diameter that the aperture is opened to is called the f/stop. When the aperture is wide, it has a small number like f/2.8 or f/4. When it’s narrow, it has a large number like f/16 or f/22.

When you adjust one setting on your camera, you’ll need to adjust the other two to get the correct exposure. You can learn everything you need about how to do this with the exposure triangle.

Newer iPhones make it easier to control the effect. I still can’t change the aperture on my iPhone 11S, but I can simulate and control shallow depth of field.

Let me give you an example. I will use PhotoPill’s online depth of field calculator to compute how far in front of and behind a subject will be in focus. It might help to open the calculator yourself and follow along.

It’s important to memorize the f/stops and each one’s effect on DOF to plan your shots. It’s easier to know that you want to shoot a scene at f/8, instead of, “that f/stop in the middle”. Below is a list of standard f/stops with 1/3 stops in between. Maximum and minimum apertures vary by lens, so yours might not have all of the f/stops listed.

Generally, an f-stop of f/2.8 has a blurrier background than an f-stop of f/16. If you want to create a shallow depth of field, select a wide aperture. Select a smaller aperture if you want more of the scene in focus.

With a wide-angle lens, you can equalize the compositions by walking closer to your subject. Doing this makes the difference in depth of field less noticeable.

There are situations where it is impossible to get a deep enough depth of field in one image. Landscape photographers sometimes struggle with this. They may find it hard to focus on a close foreground element while keeping distant elements in focus.

f-stop vsaperture

This refers to the f/stop at which a lens renders its sharpest image quality with the least degradation. It’s generally 3 stops above the lens’s maximum aperture. If a lens’ max aperture is f/2.8, the sweet spot would typically be around f/8.

Compare these two images below, taken from the same vantage point. The only setting that changed was the focal length. The first image was taken at 133mm, and the other image was taken at 100mm. Notice the change in blur in the waterlilies in the background.

A 200mm focal length gives you a field of view of about 10 degrees. A 50mm focal length gives you a field of view of 40 degrees. That’s a very different composition.

This calculator also tells me that 2.79 ft (0.85 m) in front of the subject will be in focus (30.07%). Six feet and 5 inches (2 m) behind my subject (69.93%) will be in focus. This is roughly one-third versus the two-thirds I mentioned above.

The focal length of a lens also affects the DoF. Without getting too complex, a longer focal length, like 300mm, gives you a shallower depth of field than a 35mm wide-angle lens.

If you’re aiming for a deep depth of field, you may need to figure out exactly where your focus point should be. You can figure this out by calculating the hyperfocal distance.

Paying double just for an extra f/stop may sound expensive. However, just an additional stop can make the difference in being able to capture the Milky Way with low noise, sharp hand-held photos in low light, and portraits with nice bokeh. Bokeh is how attractive the blur in the background is. The cheap kit lenses that come with mid to entry-level cameras may seem like a good deal, but they’re limiting because they have a slow maximum aperture. You control the Aperture, not the Camera In nature photography, you should virtually always control the aperture manually. This is accomplished in Aperture Priority Mode for most types of shooting, or Manual Mode in some circumstances. When the camera takes control of the aperture through Auto or Shutter Priority mode, it constantly changes the f/stop in response to changing ambient light to maintain proper exposure. This causes DOF to constantly change, altering the look of the photo. You don’t want that. f/stop affects Image Quality Lenses render their best image quality around the middle of their aperture range while suffering from different types of image degradation near their maximum and minimum f/stops. This is important because image degradation reduces the effective resolution of your hard-earned camera. You shouldn’t avoid shooting at the extremes entirely; minor image degradation may be worth the visual effect of using a specific f/stop. Every lens suffers from some amount of image degradation. It’s important to become familiar with the performance characteristics of each of your lenses to know when these problems kick in and how severe they are. The Sweet Spot This refers to the f/stop at which a lens renders its sharpest image quality with the least degradation. It’s generally 3 stops above the lens’s maximum aperture. If a lens’ max aperture is f/2.8, the sweet spot would typically be around f/8. You should use the sweet spot whenever possible. This would most typically be in compositions where DOF doesn’t matter, like when all of the elements fall within the same plane of focus. An example is a picture of a distant mountain with nothing in the near foreground. In this case, DOF would look the same whether you shot it at f/2.8 or f/16 because the mountain falls within a single plane of focus. Spherical Aberration Spherical aberration causes softness in the image center when shooting at wide f/stops. It happens because light rays passing through the edge of the lens don’t converge at exactly the same point as rays passing through the center of the lens. You can minimize it by shooting at a smaller f/stop. It’s probably worth tolerating a bit of softness from aberration if you’re after the shallowest possible DOF. Some lenses are so good that softness from aberration is barely present when shooting at wide apertures. Longitudinal Chromatic Aberration LoCA appears as red, green, yellow or bluish colored fringing along the lines and details in an image. The fringing can bleed across the image, causing it to look blurred. When present, it’s more noticeable at wide f/stops. It’s caused when the lens focuses different wavelengths of color at slightly different positions on the focal plane. LoCa is usually a minor problem that isn’t obvious on all lenses. It can be reduced by using a smaller f/stop. Fringing in the final image can be reduced in post-processing. There are several types of chromatic aberration, but LoCa is the one affected by aperture. Vignetting Vignetting is when the corners of the frame appear darkened. It’s most visible at a lens’ maximum aperture. At wide apertures, light enters the lens from various angles. Light from diagonal angles reaches the center of the camera’s sensor, but it’s physically blocked by the lens barrel from directly reaching the corners. This results in light fall-off in the corner of the image. Vignetting disappears as the f/stop approaches the lens’ sweet spot. It’s easily corrected in post-processing or can be left as a deliberate creative effect. Diffraction While the other types of image degradation happen at wide apertures, diffraction causes the image to be unsharp at small aperture. It makes the picture look slightly blurry or out of focus. Landscape photographers tend toward using small apertures for maximum DOF, but the gain in sharpness is counteracted by diffraction. It happens when light squeezes through the narrow opening of a small aperture, causing it to bend and form a distorted image. The opening of small apertures like f/16 or f/22 is a mere pinhole. On Full-frame cameras, minor diffraction becomes noticeable above f/11. Many landscape photographers automatically use f/16, unaware that diffraction might affect resolution. This was standard practice in the film days because film lacked enough resolution to actually show the effects of diffraction. However, small f/stops should only be used when necessary. When using a wide-angle lens, f/11 has sufficient DOF for most landscapes. f/16 should be reserved for scenes with close foreground objects. Cropped Format Cameras and Severe Diffraction Diffraction is more severe on cropped formats because the f/stop diameters are even smaller than the same f/stops on full-frame lenses. This applies to APS-C, Micro Four Thirds (MFT) and compact cameras. Diffraction generally worsens by the format’s crop factor when compared to full-frame. For example, MFT has a crop factor of 2x, so diffraction at f/11 is roughly as severe as a full-frame lens at f/22. Diffraction is a particularly important consideration for MFT and smaller formats because it becomes noticeable at much wider f/stops than full-frame. On MFT, diffraction becomes noticeable above f/8. Focus Stacking to avoid Diffraction So what if you need deep DOF in a photo that has a lot of detail from front to back, but want to avoid diffraction? Focus stacking is the solution. Using an f/stop near the sweet spot, you take one shot at every plane of focus and composite them together in stacking software. This creates an extremely detailed image with sharp focus through 100% of the image, with no diffraction. How to use F/stop in summary Use a large aperture like f/2.8 or f/4 to create shallow DOF with a blurry background and sharp subject Use a small f/stop like f/11 or f/16 for deep DOF with focus throughout the photo DOF also decreases by moving closer to the subject Lenses produce the best image quality around their center f/stop like f/8 Image quality degrades around their largest and smallest f/stops due to aberrations, diffraction and vignetting. Aperture is part of the exposure triangle. When you change it, you must in-turn change the ISO and Shutter Speed so light equals 100% exposure.

aperture中文

We talk about depth of field in terms of “deep” and “shallow.” Deep depth of field is also called “wide” or “large.” Shallow depth of field is also called “small” or “narrow.”

Your sensor size also affects the depth of field. Larger sensors have a shallower DoF. So, a crop sensor camera (APS-C sensor) generally has a narrower depth of field.

But with a 200mm focal length, my focus area would start at 9.68 ft (2.95 m) and extend to 10 ft (3.05 m). This is a much shallower depth of field. Only 3.94 inches (10 cm) will be in focus!

With landscapes, if you focus on the foreground, the background appears blurry. If you focus on the background, the foreground looks out of focus. To fix this, the focus needs to be somewhere in the middle between the foreground and background. This focus point is the hyperfocal distance.

Let’s give you an example. Here is a portrait of a cat taken with an iPhone. When you select Portrait mode, the camera automatically applies a background blur to the image.

The aperture also regulates the amount of light that reaches the sensor. When you close or open the aperture by one f/stop, it halves or doubles the amount of light reaching the sensor. For example, f/8 transmits twice as much light as f/11. This volume of light is interchangeably called an Exposure Value or Stop.

ExpertPhotography is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to amazon.com.

Three elements change how much of the scene is in focus. These are aperture, focal length, and relative distance. Once you know how to control the depth of field, you can decide how deep or shallow you want your focus to be.

Unlike landscape photographers, portrait photographers don’t necessarily want the entire scene in focus. If you’re taking street portraits, you want the person to be the main focus and an out-of-focus background to minimize distractions.

ExpertPhotography is part of several affiliate sales networks. This means we may receive a commission if you purchase something by clicking on one of our links.

Smartphones are limited in their ability to create blurred backgrounds. But you can still achieve the effect by getting close to your subject or using a depth-of-field simulator app.

To combat both situations, photographers use a technique called focus stacking. They take many images of a scene and change the focal point slightly with each image.

Deep and shallow depth of field fall on a continuum. You can set your aperture for an entirely sharp scene or have a very small line of focus. It’s up to you. Most photographers find a sweet spot somewhere in the middle.

f-stop是什么

Put your camera on a tripod, focus on a nearby object, and cycle through the f/stops while observing the image in your camera’s display. Note how the background becomes blurrier at wide f/stops, and sharper with small f/stops. For this to work, ensure that live view is on, which shows real-time camera settings on the display. You can also take pictures at each f/stop and view them larger on your computer for greater detail.

DOF is greater on wide-angle lenses and shallower on telephoto lenses. If using a wide-angle lens, you might have a hard time discerning the differences in DOF between f/stops. You also won’t see as big a difference if using a slow lens like f/5.6, which can’t produce a very blurred background. To partially overcome these problems, get as close to the subject as possible, which is the lens’ minimum focus distance. This creates the shallowest depth of field possible, making the effect of a blurred background more obvious.

A shallow depth of field is a great way to separate the foreground from the background. This technique is good when the background is uninteresting or distracts attention from the subject.

Imagine looking out into a landscape through your camera. Depth of field starts at the closest in-focus object and ends at the farthest in-focus object.

If your phone’s camera doesn’t have this feature, photo apps like Focos for iPhone simulate depth of field. Apps like this change the aperture virtually. Using the Focos app, we created an image that simulated an f/20 aperture (middle photo) and f/1.4 (right)

The amount of available light always dictates the settings that you can use, and sometimes you won’t be able to use the exact f/stop that you want. In dim light for example, you can’t simultaneously use a small f/stop, low ISO and fast shutter speed. This combination would transmit less than 100% light, leaving the photo underexposed. You have to sacrifice one of these settings or a little bit from each to add more exposure. If hand-holding the camera in dim light, you’d have to keep a fast shutter speed to prevent blur from camera shake, while using a wide f/stop to transmit enough light.

But because they are close to their subjects with long-focal length lenses, the depth of field is often very shallow. You can see this in the close-up of spoons on a textured background below.

In nature photography, you should virtually always control the aperture manually. This is accomplished in Aperture Priority Mode for most types of shooting, or Manual Mode in some circumstances. When the camera takes control of the aperture through Auto or Shutter Priority mode, it constantly changes the f/stop in response to changing ambient light to maintain proper exposure. This causes DOF to constantly change, altering the look of the photo. You don’t want that.

First, I enter my camera body (Sony a7R IV) and choose f/8. To be consistent, I’ll keep my subject’s distance at 10 ft (3 m). I’ll first enter 50mm as the focal length of my lens, then change it to 200mm.

While this may sound like a lot of juggling, you don’t actually have to control all three of the settings yourself. Using an auto mode like Aperture Priority lets you control the aperture while the camera takes care of the rest.

In the image below, only the foreground is in focus. The background gives a sense of the environment without distracting from the foreground. The foreground flowers are in focus, while the background of the garden is blurred.

Aperture

I’ll show you how to achieve deep and shallow depth of field. But there’s one more thing you need to know about the focus area.

If you’re not getting the depth of field you want, the next thing to change is relative distance. You can try getting closer to your subject. If that doesn’t help, move your subject away from the background.

With a 50mm focal length, my focus area would start at 7.68 ft (2.34 m) and extend to 13.71 ft (4.18 m). Everything within this 6.03 ft (1.84 m) range will be in sharp focus.

F-stops

Understanding depth of field is crucial. It empowers you to manipulate focus creatively, which leads to captivating images. Mastering this concept lets you intentionally control sharpness and blur.

I didn’t cover this variable because most photographers don’t change their camera body to control the depth of field. I mention this if you compare images with a friend with a different camera body.

The DoF calculator (image below) says the nearest point in focus is 7.05 ft (2.15 m) away. The furthest point in focus is 16.37 ft (4.99 m).

You can use this mode to get a blurred background, even if you’re not shooting portraits. The original settings of the first photo on the left were 9.0mm, f/2.8, 1/121 s, and ISO 32. Clicking the edit button gives you some options to change the aperture.

The DoF calculator also tells me the hyperfocal distance. This is important for landscape photographers. Hyperfocal distance tells me where to focus in the scene to get a sharp focus to infinity. (Infinity is as far as the eye can see.)

Changing your aperture (f-stop) is one of the best ways of changing the DoF. Generally, the wider the aperture, the shallower the depth of field, and vice versa. Remember that wide apertures have small f-numbers.

Macro photographers use long macro lenses to capture small subjects like flowers and insects. These lenses let photographers get very close to their subjects.

If you are taking a portrait, a very wide aperture like f/1.2 can put the eyes in focus while the nose and ears are blurry. Using the same f-stop, you can focus on the nose, but this will blur the eyes.

Lenses render their best image quality around the middle of their aperture range while suffering from different types of image degradation near their maximum and minimum f/stops. This is important because image degradation reduces the effective resolution of your hard-earned camera. You shouldn’t avoid shooting at the extremes entirely; minor image degradation may be worth the visual effect of using a specific f/stop. Every lens suffers from some amount of image degradation. It’s important to become familiar with the performance characteristics of each of your lenses to know when these problems kick in and how severe they are.

So what if you need deep DOF in a photo that has a lot of detail from front to back, but want to avoid diffraction? Focus stacking is the solution. Using an f/stop near the sweet spot, you take one shot at every plane of focus and composite them together in stacking software. This creates an extremely detailed image with sharp focus through 100% of the image, with no diffraction.

Depth of field (DoF) refers to how much of your scene is (and isn’t) in focus. Photographers often manipulate the depth of field as a creative choice. They do this by selecting the right aperture for the scene they want to create.

Ms.Cici

Ms.Cici

8618319014500

8618319014500